A bit random

Feynman The meaning of it all

https://antilogicalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/meaning-of-it-all.pdf

**

noticing design

https://x.com/culturaltutor/status/1975600972056375541

**

elec https://chatgpt.com/share/68ede765-1fac-8010-9c24-e8ec9e232b6e

electricity

“Once upon a time, there were power companies that instead of electricity distributed power literally by pumping pressurized water through a network of pipes. In many ways water flow is exactly the same thing as the flow of electrons, only without generation of the electric and magnetic fields around the conductors.”

strange deaths https://www.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/16enk8h/what_celebrity_death_seems_a_bit_too_suspicious/

There’s been a lot of recent debate about how to recognize the Antichrist, and I might have more to say about this later, but for now I think people are really sleeping on the forehead inscription.

do it now, momentum, Gen Z

https://substack.com/home/post/p-157766034

ethos https://stlcc.edu/student-support/academic-success-and-tutoring/writing-center/writing-resources/pathos-logos-and-ethos.aspx

https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/ethos-pathos-logos/

You are the sum of/the average of the 5 people you spend most time with.

truth and stats

from slate star William James did an experiment with nitrous oxide and write about it:

It is impossible to convey an idea of the torrential character of the identification of opposites as it streams through the mind in this experience. I have sheet after sheet of phrases dictated or written during the intoxication, which to the sober reader seem meaningless drivel, but which at the moment of transcribing were fused in the fire of infinite rationality. God and devil, good and evil, life and death, I and thous, sober and drunk, matter and form, black and white, quantity and quality, shiver of ecstasy and shudder of horror, vomiting and swallowing, inspiration and expiration, fate and reason, great and small, extent and intent, joke and earnest, tragic and comic, and fifty other contrasts figure in these pages in the same monotonous way. The mind saw how each term belonged to its contrast through a knife-edge moment of transition which it effected, and which, perennial and eternal, was the nunc stans of life. The thought of mutual implication of the parts in the bare form of a judgement of opposition, as “nothing–but,” “no more–than,” “only–if,” etc., produced a perfect delirium of the theoretic rapture. And at last, when definite ideas to work on came slowly, the mind went through the mere form of recognizing sameness in identity by contrasting the same word with itself, differently emphasized, or shorn of its initial letter. Let me transcribe a few sentences.

What’s mistake but a kind of take?

What’s nausea but a kind of -usea?

Sober, drunk, -unk, astonishment.

Everything can become the subject of criticism —

How criticise without something to criticise?

Agreement — disagreement!!

Emotion — motion!!!!

By God, how that hurts! By God, how it doesn’t hurt!

Reconciliation of two extremes.

By George, nothing but othing!

That sounds like nonsense, but it is pure onsense!

Thought deeper than speech…!

Medical school; divinity school, school! SCHOOL!

Oh my God, oh God; oh God!The most coherent and articulate sentence which came was this: There are no differences but differences of degree between different degrees of difference and no difference.

**

Derek Thompson “Show me the last 5 — or 25 — photos/screenshots you took of something interesting” is a fun window into the mind of strangers.

**

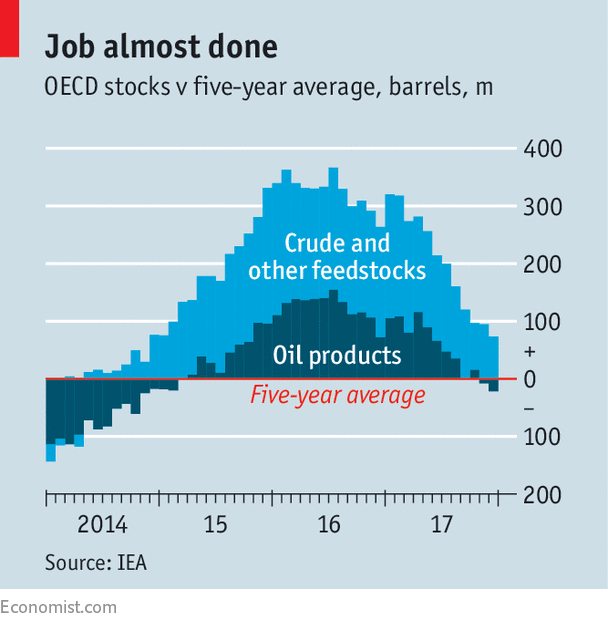

Zucman tax

a minimum tax on billionaires equal to 2% of their wealth would raise $200-$250 billion per year globally from about 3,000 taxpayers; extending the tax to centimillionaires would add $100-$140 billion; (iv) this international standard would effectively address regressive features of contemporary tax systems at the top of the wealth distribution; (v) it would not substitute for, but support domestic progressive tax policies, by improving transparency about top-end wealth, reducing incentives to engage in tax avoidance, and preventing a race to the bottom; (vi) its economic impact must be assessed in light of the observed pre-tax rate of return to wealth for ultra-high-net-worth individuals which has been 7.5% on average per year (net of inflation) over the last four decades, and of the current effective tax rate of billionaires, equivalent to 0.3% of their wealth.

from https://www.taxobservatory.eu/publication/a-blueprint-for-a-coordinated-minimum-effective-taxation-standard-for-ultra-high-net-worth-individuals/

***

astral codex

Wikipedia on impossible colors:

In 1983, Hewitt D. Crane and Thomas P. Piantanida performed tests using an eye-tracker device that had a field of a vertical red stripe adjacent to a vertical green stripe, or several narrow alternating red and green stripes (or in some cases, yellow and blue instead). The device could track involuntary movements of one eye (there was a patch over the other eye) and adjust mirrors so the image would follow the eye and the boundaries of the stripes were always on the same places on the eye's retina; the field outside the stripes was blanked with occluders. Under such conditions, the edges between the stripes seemed to disappear (perhaps due to edge-detecting neurons becoming fatigued) and the colors flowed into each other in the brain's visual cortex, overriding the opponency mechanisms and producing not the color expected from mixing paints or from mixing lights on a screen, but new colors entirely, which are not in the CIE 1931 color space, either in its real part or in its imaginary parts. For red-and-green, some saw an even field of the new color; some saw a regular pattern of just-visible green dots and red dots; some saw islands of one color on a background of the other color. Some of the volunteers for the experiment reported that afterward, they could still imagine the new colors for a period of time.

How is this just sitting hidden in a random Wikipedia article? How come there’s no science museum or amusement park where I can use the see-the-impossible-color machine?

5: Elizabeth VN: My Resentful Story Of Becoming A Medical Miracle. This is one of the best examples I’ve read of how a lot of medicine for chronic poorly understood complaints works; doctors shrug, you try dozens of purported miracle cures over the course of decades, if you’re extremely lucky then one of them works, you never learn why or become able to generalize it to other people.

6: Apparently there’s a video podcast with Jordan Peterson and Karl Friston, I haven’t seen it because I don’t watch videos, but it’s an interesting thing to have exist.

City Journal (quoted in Marginal Revolution) on the trend to bar scientists from accessing government datasets if their studies might get politically incorrect conclusions (obviously this isn’t how the policy’s proponents would describe it, they would probably say something about promoting equity and safety). Originally this was just about a few topics around race and IQ, but now it’s expanded to everything from genetic determinants of obesity to the way Alzheimers lowers IQ.

14: Aella on color synaesthesia. Lots of people report feeling like certain numbers are certain colors - but which ones?

here is a lot of debate over whether “critical race theory” is being taught in schools. Zack Goldberg and Eric Kaufmann surveyed 18-20 year-olds about what they were “taught in class or heard an adult say in school” and got nationally representative data. I assume that means we can shift to an exactly equally acrimonious debate over whether the specific things the survey found do or don’t qualify as “critical race theory”. In case it helps, here are some of their figures:

If they stop teaching CRT in schools and need to know what to replace it with, I recommend a lesson on making readable graphs.

**

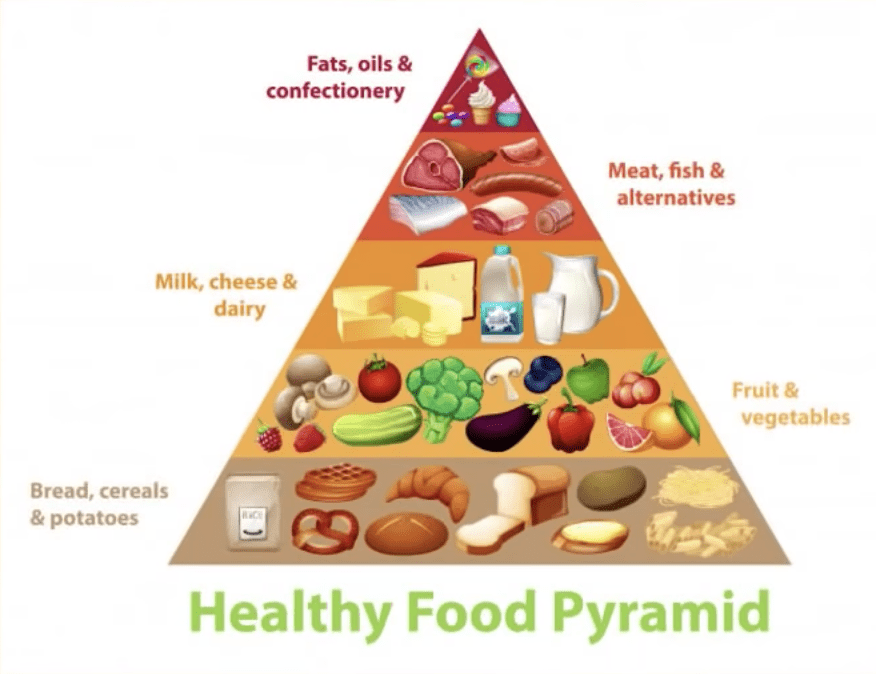

food

from https://petermeglis.com/blog/hamzas-full-written-diet-guide/#the-obesity-pandemic

to do Scott

“I started with Does Class Warfare Have A Free-Rider Problem, and it took me way too long to figure out that this was one of the major questions sociology was asking, and that “an answer” would look less like “your game theory analogy is missing this one variable” and more like a whole library full of books on what the heck society was. Later the same engagement produced Conflict Vs. Mistake, “Obviously some questions are easier than others, but the disposition to view questions as hard or easy in general seems to separate into different people and schools of thought.”

The network, theoretically we all know this- but practically

see Einstein and Emmy Noether, Emilie du Chatelet,

Pay Pal mafia, YCombinator (Sam)

Open ai, spinoffs, Mira Murati, Anthropic,

Sam Altman - just come up with an idea

**

comparative advantage steel

https://x.com/Rainmaker1973/status/1961666441700319384

more slare star ACX

predictive coding theory of the brain. I started groping towards it (without knowing what I was looking for) in Mysticism And Pattern-Matching, reported the exact moment when I found it in It’s Bayes All The Way Up, and finally got a decent understanding of it after reading Surfing Uncertainty. At the same time, thanks to some other helpful tips from other rationalists, I discovered Behavior: The Control Of Perception, and with some help from Vaniver and a few other people was able to realize how these two overarching theories were basically the same. Discovering this area of research may be the best thing that happened to me the second half of this decade (sorry, everyone I dated, you were pretty good too).

Psychedelics are clearly interesting, and everyone else had already covered all the interesting pro-psychedelic arguments, so I wrote about some of my misgivings in my 2016 Why Were Early Psychedelicists So Weird?. The next step was trying to fit in an understanding of HPPD, which started with near-total bafflement. Predictive processing proved helpful here too, and my biggest update of the decade on psychedelics came with Friston and Carhart-Harris’ Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics And The Anarchic Brain, which I tried to process further here. This didn’t directly improve my understanding of HPPD specifically, but just by talking about it a lot I got a subtler picture where lots of people have odd visual artifacts and psychedelics can cause slightly more (very rarely, significantly more) visual artifacts. I started the decade thinking that “psychedelic insight” was probably fake, and ended it believing that it is probably real, but I still don’t feel like I have a good sense of the potential risks.

In mental health, the field I am supposed to be an expert on, I spent a long time throwing out all kinds of random ideas and seeing what stuck – Boorsboom et al’s idea of Mental Disorders As Networks, The Synapse Hypothesis of depression, etc. Although I still think we can learn something from models like those, right now my best model is the one in Symptom, Condition, Cause, which kind of sidesteps some of those problems. Again, learning about predictive processing helped here, and by the end of the decade I was able to say actually useful things that explained some features of psychiatric conditions, like in Treat The Prodrome. Friston On Computational Mood might also be in this category, I’m still waiting for more evidence one way or the other.

I also spent a lot of time thinking about SSRIs in particular, especially Irving Kirsch (and others’) claim that they barely outperform placebo. I wrote up some preliminary results in SSRIs: Much More Than You Wanted To Know, but got increasingly concerned that this didn’t really address the crux of the issue, especially after Cipriani et al (covertly) confirmed Kirsch’s results (see Cipriani On Antidepressants). My thoughts evolved a little further with SSRIs: An Update and some of my Survey Results On SSRIs. But my most recent update actually hasn’t got written up yet – see the PANDA trial results for a preview of what will basically be “SSRIs work very well on some form of mental distress which is kind of, but not exactly, depression and anxiety”.

One place I just completely failed was in understanding the psychometrics of autism, schizophrenia, transgender, and how they all related to each other and to the normal spectrum of variation. I kind of started this program with Why Are Transgender People Immune To Optical Illusions? (still a good question!), fumbled around by first-sort-of-condemning and then sort-of-accepting the diametrical model of autism and schizophrenia, and then admitting I just didn’t know what was going on in this area and not talking about it much more. I still sometimes have thoughts like “Is borderline the opposite of autism?” or “Are schizoid people unusually charismatic, unusually uncharismatic, or somehow both?”, and I still have no idea how to even begin answering them. Autism And Intelligence: Much More Than You Wanted To Know at least helped address a very tangentially related question and is probably the closest thing to a high point this decade gave me here.

The Nurture Assumption shaped my 2000s views of genetics and development. Ten years later, I’m still trying to process it, and in particular to square the many behavioral genetics studies showing nonshared environment doesn’t matter with the many other studies suggesting it does (see eg The Dark Side Of Divorce and Shared Environment Proves Too Much). I think I started to get more of handle on attachment theory and cPTSD as both being different aspects of the same basic predictive processing concept of “a global prior on the world being safe” – see Mental Mountains and Evolutionary Psychopathology for two different ways of approaching this concept. This made me conclude that I might have been wrong about preschool (though see also Preschool: Much More Than You Wanted To Know). Honestly I am still confused about this. The one really exciting major good update I made about genetics this decade was understanding and fully internalizing the omnigenic model.

One of the big motivating questions I keep coming back to again and again is – what the heck is “willpower”? I started the decade so confused about this that I voluntarily bought and read Baumeister and Tierney’s book Willpower and expected it to be helpful. I spent the first few years gradually internalizing the lesson (which I learned in the 2000s) that Humans Are Not Automatically Strategic (see also The Blue-Minimizing Robot as a memorial to the exact second I figured this out), and that hyperbolic discounting is a thing. Since then, progress has been disappointing – the only two insights I can be even a little happy about are understanding perceptual control theory and Stephen Guyenet’s detailed account of how motivation works in lampreys. If I ever become a lamprey I am finally going to be totally content with how well I understand my motivational structure, and it’s going to feel great.

Speaking of Guyenet, if nothing else this last decade has taught us that Gary Taubes did not solve all of nutrition in 2004, that Atkins/paleo/keto are good for some people and bad for others, and that diet is still hard. See the various Guyenet vs. Taubes and Taubes vs. Guyenet posts, and my 2015 The Physics Diet on where I was at that point. So what is going on with diet? Compressing an entire decade’s worth of research into two words, the key phrase seems to be “set point” (which, credit to Taubes, he was one of the first people to popularize). See eg Anorexia And Metabolic Set Point and Del Giudice On The Self-Starvation Cycle. But what is the set point and how does it get dysregulated? See my book review of The Hungry Brain for the best answer to that I have now (not so good). This whole mess helped me get a better understanding of Contrarians, Crackpots, and Consensus, and eventually ended up with me Learning To Love Scientific Consensus.

In terms of x-risk: I started out this decade concerned about The Great Filter. After thinking about it more, I advised readers Don’t Fear The Filter. I think that advice was later proven right in Sandler, Drexler, and Ord’s paper on the Fermi Paradox, to the point where now people protest to me that nobody ever really believed it was a problem. AI has been the opposite – I feel like the decade began with people pooh-poohing it, my AI Researchers On AI Risk was part of a large-scale effort to turn the tide, and now it’s more widely accepted as an important concern. At the same time, the triumphs of deep learning has made things look a little different – see How Does Recent AI Progress Affect The Bostromian Paradigm? and Reframing Superintelligence – and I’ll be reviewing Human Compatible soon. I also got some really great insights on what “human-level intelligence” means from the good people at AI Impacts, which I wrote up as first Where The Falling Einstein Meets The Rising Mouse and later Neurons And Intelligence: A Bird-Brained Perspective (see also Cortical Neuron Number Matches Intuitive Perceptions Of Moral Value Across Animals and all the retractions and meta-retractions thereof). Overall I think I’ve updated a little (though not completely) towards non-singleton scenarios and not-super-fast takeoffs, which combined with the increased amount of effort being put into this area is cause for a little more optimism than I had in 2010. I know some smart people disagree with me on this.

In the 2000s, people debated Kurzweil’s thesis that scientific progress was speeding up superexponentially. By the mid-2010s, the debate shifted to whether progress was actually slowing down. In Promising The Moon, I wrote about my skepticism that technological progress is declining. A group of people including Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen have since worked to strengthen the case that it is; in 2018 I wrote Is Science Slowing Down?, and late last year I conceded the point. Paul Christiano helped me synthesize the Kurzweillian and anti-Kurzweillian perspectives into 1960: The Year The Singularity Was Cancelled.

In 2017, I synthesized some thoughts that had been bouncing around about rising prices into Considerations On Cost Disease, still one of this blog’s most popular posts. I felt like early responses were pretty weak, although they brought up a few interesting points on veterinary medicine, cosmetic medicine, and other outliers that I still need to transform into a blog post; Alon Levy’s work on infrastructure in particular has also been great. The first would-be-general-answer that made me sit up and take notice was Alex Tabarrok’s book (link goes to my review) The Prices Are Too Damn High – but I explain there why I don’t think it can be the full answer. The most recent thing I learned (tragically underhighlighted in my wage stagnation post) is that a lot of apparent wage stagnation is due to cost disease – consumer services ballooning in cost means the consumer inflation index rises faster than the business inflation index, productivity gets measured by business inflation, wages get measured by consumer inflation, and so it looks like productivity is outpacing wages. This is still only half of the apparent decoupling, but it’s still a big deal.

The highlight/lowlight of the decade in social science was surely the replication crisis. My first inkling that something like this might exist was in December 2009, from the Less Wrong post Parapsychology: The Control Group For Science. There were a couple of years where people were trying to figure out how bad the damage was; of these, my 90% Of All Claims About Problems With Medical Studies Are Wrong was more optimistic, and my slightly later The Control Group Is Out Of Control was more pessimistic (I still stand by both). As the decade continued, I think we got better about realizing that many to most older studies were wrong, in a way that didn’t make us feel like total Cartesian skeptics or like we were going to have to throw out evolution or aspirin or any of the things on really sound footing. After that it just became fun: my “acceptance” stage of grief produced some gems like 5-HTTLPR: A Pointed Review.

On SSC, I particularly examined some of the replication issues of growth mindset. I started in 2015 by pointing out that the studies seemed literally unbelievable, but so far nobody had tried attacking them. I claim to have been way ahead of the curve on this one – if you don’t believe me, just read the kind of pushback I got. But by 2017, that situation had changed – Buzzfeed posted an article that called the field into question, but still without clear negative evidence. Finally, over the past few years, the negative studies have come pouring in, accented by supposedly “positive” studies by Dweck & co showing effect sizes only a tiny fraction of what they had originally claimed. The latest research (can’t find it right now) is that praising students for effort rather than for ability has no effect on how hard-working or successful they are, debunking the original headline result that got most people interested in the field and nicely closing the circle.

In 2010 I worked with a medical school professor who studied the placebo effect and realized I didn’t understand it at all. Over the past few years I gradually became more convinced of the heterodox position of Gøtzsche and Hróbjartsson, who believe placebo effect doesn’t apply to anything except pain and a few other purely mental phenomena (The Placebo Singers, Powerless Placebos). I’ve since become less convinced that’s true (just today I treated a patient who I’m pretty sure has psychosomatic vomiting from what he falsely believes was a medication side effect, and if belief can cause vomiting, surely it can also treat it). As with so many other things, it was predictive processing to the rescue – see section IV part 7 of my Surfing Uncertainty review. I now think I have a pretty good understanding of how placebos can treat both purely mental conditions and conditions heavily regulated by the nervous system, while still mostly sticking to Gøtzsche and Hróbjartsson’s findings.

I started this decade confused about how to understand ethics given all the paradoxes of utilitarianism. I’m still 90% as confused now as I was then, but I still feel like I’ve made some progress. A lot of my early thinking involved folk decision theory and contractualism – how would you act if you expected everyone else to act the same way? I explored the edges of this idea in You Kant Dismiss Universalizability and Invisible Nation. I’m not how much it helped my search for metaethical grounding, but it helped me get a more robust understanding of liberalism and clarify my views on some practical questions, eg Be Nice, At Least Until You Can Coordinate Meanness and The Dark Rule Utilitarian Argument For Science Piracy. In general I think this has given me a more cautious theory of decision-making that’s occasionally (and terrifyingly) set me against other more anti-Outside-View rationalists. I think the most important shift in my understanding of ethics this decade was the one I wrote up in Axiology, Morality, Law (formerly titled “Contra Askell On Moral Offsets”), which isn’t related to grounding utilitarianism at all but sure helps make the problem less urgent

Despite my better judgment, I waded into politics a lot this decade. I Can Tolerate Anything Except The Outgroup produced this blog’s first “big break”, but it admitted it didn’t really understand the factors underlying “tribe”. Since then Albion’s Seed helped provide another piece of the puzzle, and a better understanding of class provided another. I went a little further discussing why tribes have ideologies associated with them in The Ideology Is Not The Movement, how that is like/unlike religion in Is Everything A Religion?, and hammered it home unsubtle-ly in Gay Rites Are Civil Rites.

I wrote the Non-Libertarian FAQ sometime around 2012 and last updated it in 2017. Sometime, possibly between those dates, I read David Friedman’s A Positive Account Of Property Rights, definitely among the most important essays I’ve ever read, and got gold-pilled (is that a term? It should be a term). I’ve since been trying to sort this out with things like A Left-Libertarian Manifesto, and trying to move them up a level as Archipelago. James Scott’s Seeing Like A State and David Friedman’s Legal Systems Very Different From Ours were also big influences here. Like all platitudes, “government is a hallucination in the mind of the governed” is easy to understand on a shallow level but fiendlishly complicated on a deep level, but I feel like all of these sources have given me a deep understanding of exactly how it’s true.

The rightists (especially Moldbug) get the other half of the credit for helping me understand Archipelago, and also deserve kudos for teaching me about cultural evolution. My first attempts to engage with this topic were nervous and halting – see eg The Argument From Cultural Evolution. I got a much better feel for this after reading The Secret Of Our Success, and was able to bring this train of thought back to its right-wing roots Addendum To Enormous Nutshell: Competing Selectors. I’m grateful to the many rightists who argued about some of these points with me until they finally stuck.

I had more trouble engaging with leftists. I started with Does Class Warfare Have A Free-Rider Problem, and it took me way too long to figure out that this was one of the major questions sociology was asking, and that “an answer” would look less like “your game theory analogy is missing this one variable” and more like a whole library full of books on what the heck society was. Later the same engagement produced Conflict Vs. Mistake, which I am informed is still unfair and partially inaccurate, but which (take my word for it) is a heck of a lot better than the stuff I was thinking before I wrote it. More recently I’ve been trying to figure out a sympathetic account of activism (as opposed to the unsympathetic account that it’s virtue signaling and/or people who are really bad at figuring out what things are vs. aren’t effective). You can sketch the outline at Respectability Cascades and Social Censorship: The First Offender Model, and I’ll sketch the whole thing out sometime when I have enough emotional energy to deal with the kind of people who will have opinions on it.

I also had to grapple with the sudden rise of social justice ideology. I’m proud of my work on gender differences – both what I learned, how I wrote it up, and the few bits of original research I did (eg Sexual Harassment Levels By Field). My knowledge and claims started off kind of weak (Gender Differences Are Mostly Not Due To Offensive Attitudes), but I eventually feel like I got a really great evidence-based basically-airtight theory of what is going on with gender imbalances in different fields, which I posted most of in Contra Grant On Exaggerated Differences (I’m still thankful for the commenter who solved that one remaining paradox about math majors). And despite all the mobs and vitriol I think sound science has basically triumphed here – I was delighted to recently see as mainstream a blog as Marginal Revolution recently publish, without any caveats or double-talk, a post called Sex Differences In Personality Are Large And Important and get basically no pushback. I was a lot more pessimistic around 2017 or so and described some thoughts on how to make a strategic retreat in Kolmogorov Complicity And The Parable Of Lightning, which I still think is relevant in some areas. But I actually start the new decade really optimistic – I haven’t written up an explanation of why, but careful readers of New Atheism: The Godlessness That Failed may be able to figure it out, especially if they apply some of the same metrics I used there to track how social justice terms have been doing recently.

Upstream of politics, I think I got a better understanding of…game theory? Complex system dynamics? The most important post here was Meditations On Moloch; the sequel/expansion, whose thesis I have yet to write up in clear prose, is The Goddess Of Everything Else. Reading Inadequate Equilibria was also helpful here.

My understanding of “enlightenment” went from total mystical confusion to feeling like I have a pretty good idea what claims are being made, and mostly believing them. This line of thinking started with the Mastering The Core Teachings Of The Buddha review, and then was genuinely helped by Vinay Gupta’s contributions summed up in Gupta On Enlightenment, despite the disaster in the comments of that post. From there I progressed to reading The Mind Illuminated, and Is Enlightenment Compatible With Sex Scandals led me to discover The PNSE Paper, which as much as anything else helped ground my thinking here (the comments there were pretty good too).

And thanks to all of you who took the survey, I went from skepticism of birth order effects to saying Fight Me, Psychologists: Birth Order Effects Exist And Are Very Strong. This was bolstered by Eli Tyre and Bucky’s posts on Less Wrong about birth order in mathematicians and physicists respectively. Last year I expanded on that with a post on how birth order responded to age gaps (somewhat updated and modified here, thanks Bucky).

Not many of these were total 180 degree flips in my position (though birth order, preschool, psychedelic insight, and the rate of scientific progress are close).

166 Responses to What Intellectual Progress Did I Make In The

**

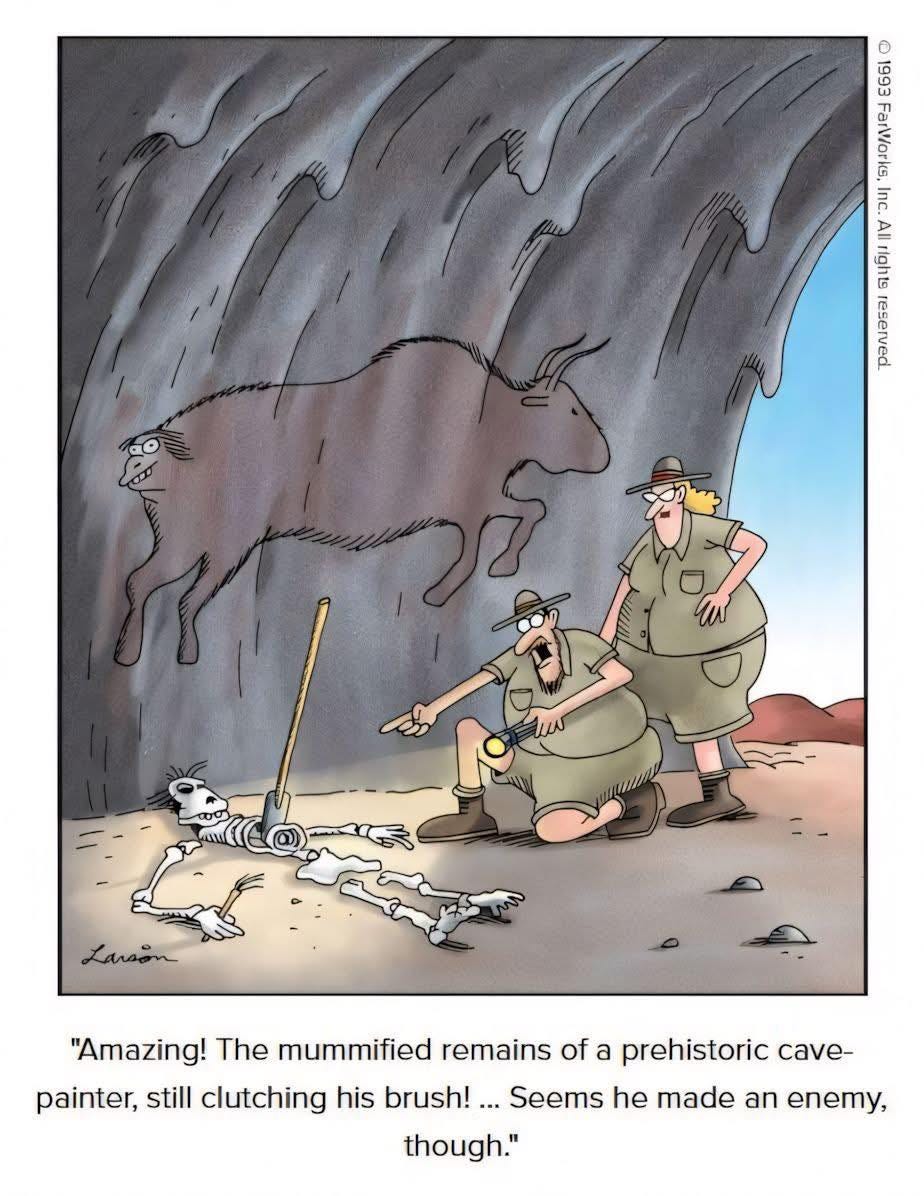

and some things that just made me smile

*

see courage

and the opposite- food companies and chemical companies, deliberately trying to make people obese and kill them

*

look upon my works, ye mighty

**

diamond peak oil ruppert

https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01603/WEB/SYSTEMS_.HTM

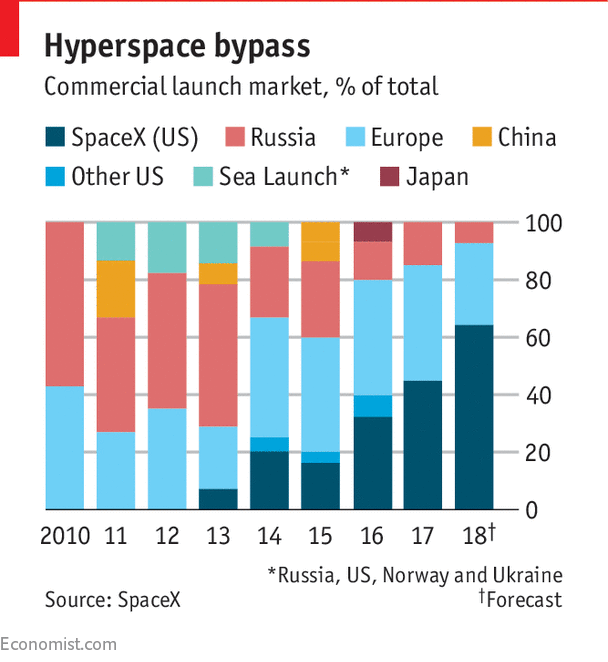

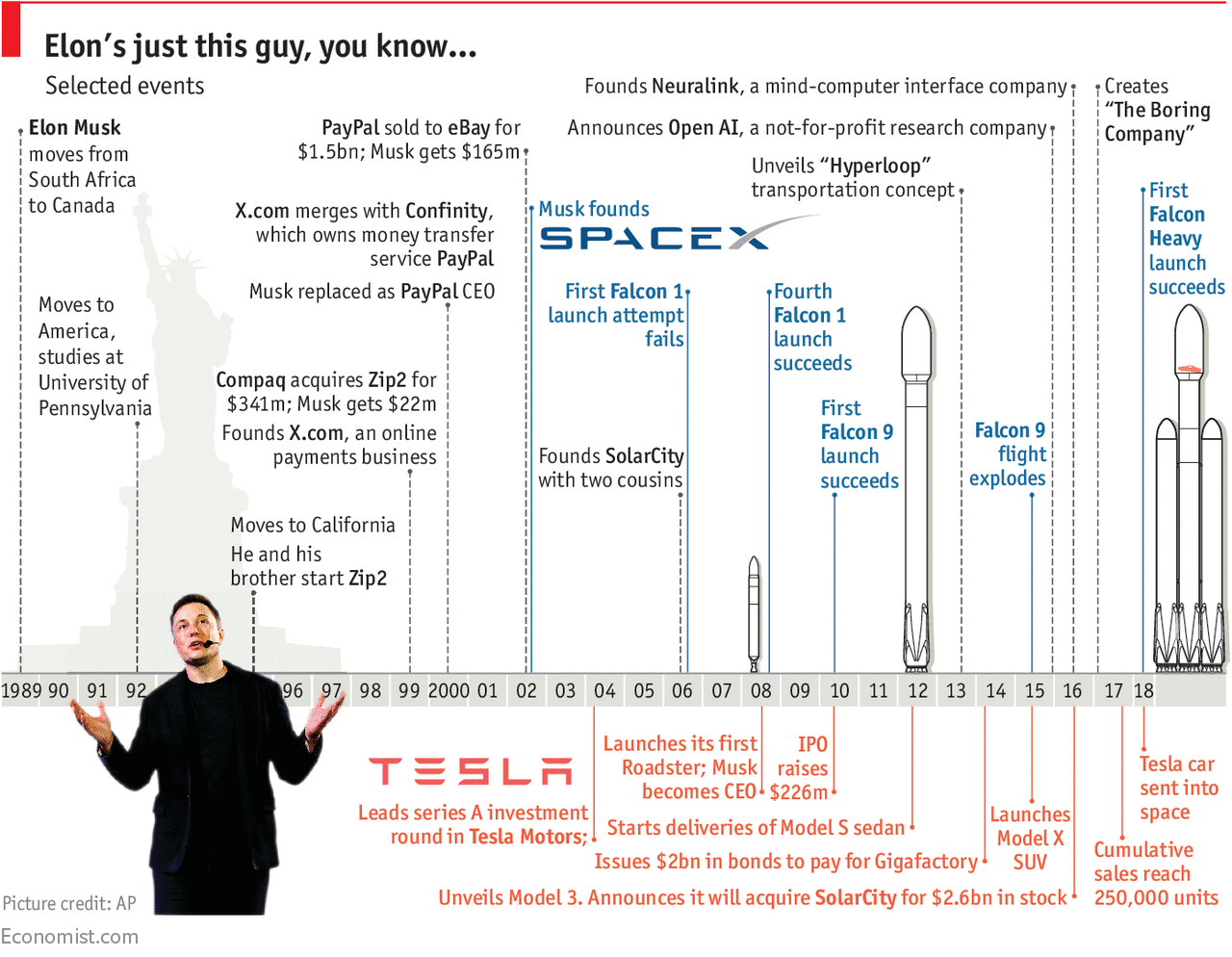

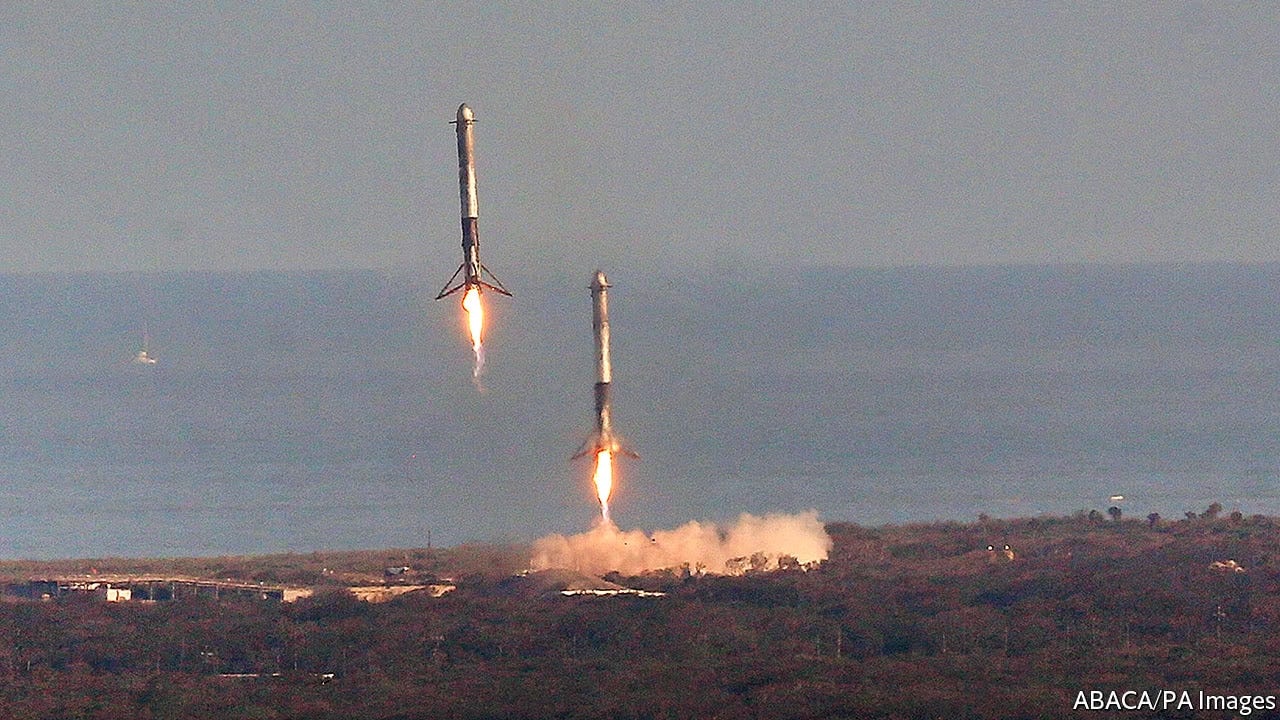

musk

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/CYTwRZtrhHuYf7QYu/a-case-for-courage-when-speaking-of-ai-danger

(Nate Soares)

but i didn't have the time

https://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/04/28/shorter-letter/

https://withoutbullshit.com/blog/paul-romer-set-reform-writing-world-bank-lost-job

http://timharford.com/articles/undercovereconomist/articles/otherwriting/

systems approach?

https://blogs.worldbank.org/publicsphere/what-systems-approach-anyway

What is a systems approach, anyway? | People, Spaces ...

“It makes me a little crazy when you keep saying systems.” – Jowhor Ile, in And After Many Days At home, we have a porchlight at the entrance to our house. If I ...

peterson you would be a nazi

Forgotten Hero | Hugh Thompson Jr.

Mary Harrington in Unherd

“One of the prevailing divisions can be crudely summed up as “nationalist” versus “globalist”. That is: on one side, a belief that groups of people are entitled to draw boundaries around an in-group, and confer privileges to that group based on internally determined measures of belonging. This is the worldview held, by and large, by the majority of Americans who support Trump’s deportation programme: citizenship means something, and you shouldn’t get to be an American citizen, with all its perks, just by crossing a border and existing in the country for a given period of time. For this group, deporting people in the country illegally is obviously the right course of action.

Against this stand a range of more or less utopian globalists, who believe national boundaries are variously arbitrary, cruel, racist and/or fascist, or simply bad for the economy. A cluster of such sentiments, for example, animates a recent Washington Post article lamenting the deportation from wealthy New England holiday island Martha’s Vineyard of “undocumented workers who form the backbone of the workforce”. The article’s hand-wringing over the impact of ICE raids on local pool maintenance and construction projects offers a clue as to the role played by “undocumented workers” in such elite playgrounds: a fortunate convergence of utopian ideals with economic interest.”

***

trends cremieux

***

https://x.com/weirddalle/status/1937080989638951055

performative?

https://x.com/UNGeneva/status/1929946397245051178

***

billions and trillions

https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1930146068286845200

***

More on Bayes

Eliezer wrote his famous essay back in 2003 (which Khalid Azad helpfully summarized in 2007), Steven Pinker in Rationality, Julia Galef speaks about it on BigThink,Nietzsche’s “Dionysian” vs. “Apollonian” modes, and to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s “the bricoleur” vs. “the engineer”, and to Alasdair MacIntyre’s critique of modernity. Erik Hoel’s “intrinsic” vs. “extrinsic” perspectives.

Kahneman’s “System 1” and “System 2” and Jonathan Haidt’s “the elephant” and “the rider”.

**

Don’t look to see if an issue is supported by the left or the right before deciding what your view is.

expanding universe

“We can only observe part of the universe—the "observable universe"—which is expanding.

It's possible the entire universe is infinite and has always been infinite, so asking "what it's expanding into" is meaningless. It's just getting less dense.

The boundary we talk about (46 billion light-years away) is not an edge—just the limit of what light has had time to reach us from.”

**

from fb

from fb

**

**

***

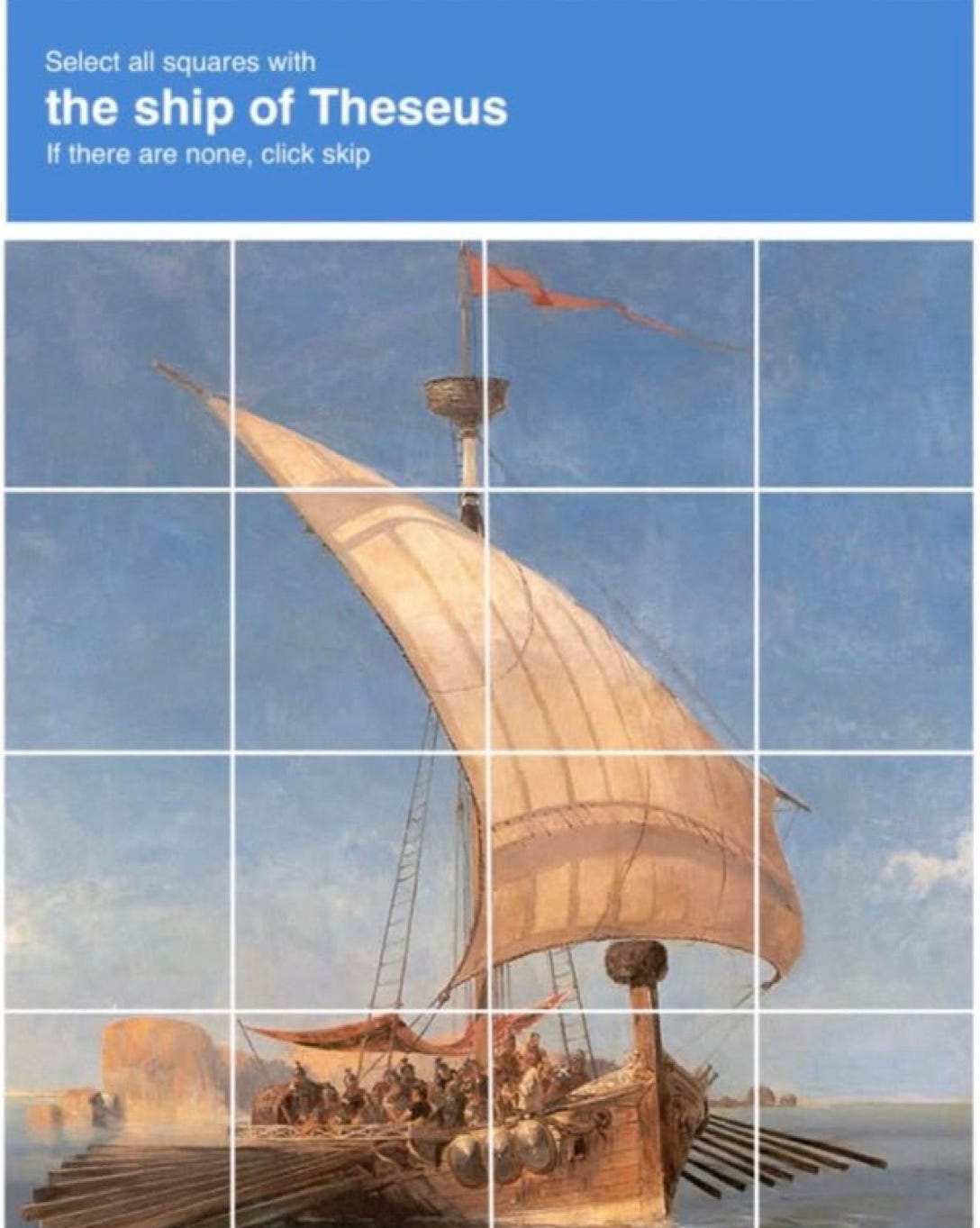

*****

In its original formulation, the "Ship of Theseus" paradox concerns a debate over whether or not a ship that has had all of its components replaced one by one would remain the same ship.[1] The account of the problem has been preserved by Plutarch in his Life of Theseus:[2]

The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned from Crete had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and strong timber in their places, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.

— Plutarch, Life of Theseus 23.1

Over a millennium later, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes extended the thought experiment by supposing that a ship custodian gathered up all of the decayed parts of the ship as they were disposed of and replaced by the Athenians, and used those decayed planks to build a second ship.[2] Hobbes then posed the question of which of the two resulting ships—the custodian's or the Athenians'—was the same ship as the "original" ship.[1]

from Philosophy matters on fb

***

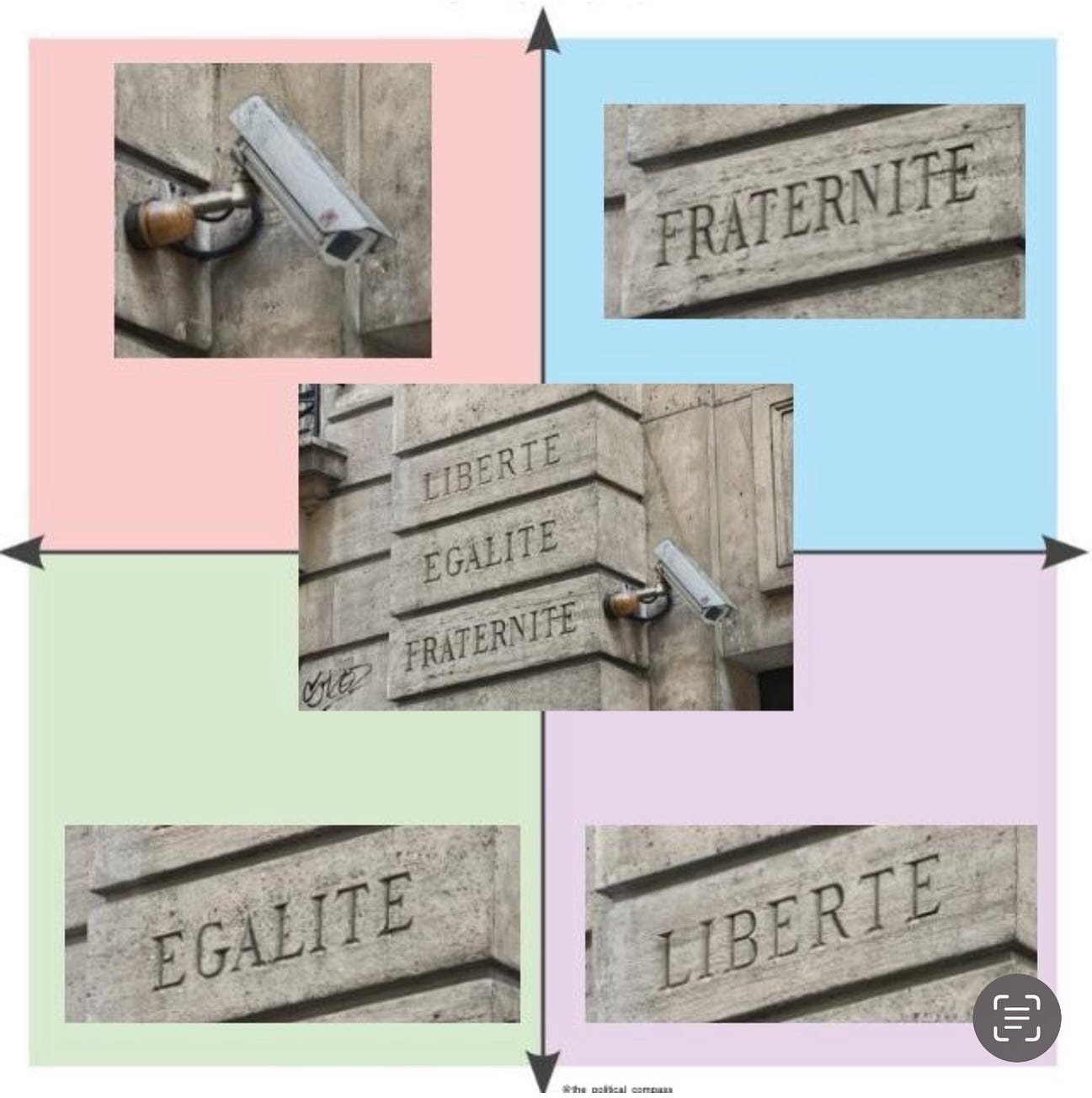

from political compass

from Carrick Ryan

“It then uses a statistical model to predict the most likely next word based on the conversation so far, based on patterns it learned during training.

But it's not just guessing which word comes next in each sentence. It builds internal representations of meaning, relationships, logic, and style over long spans of text.

It can reason, summarise, infer, translate, solve problems, and write original code or essays; not because it "knows" or "understands" like a human, but because it has learned to model the patterns of language and thought so well it is almost indistinguishable from a human mind.

It doesn't tell us the truth, it makes a calculation on what the truth is statistically most likely to be based on the written records of our language.”

check out population density chart then Danes!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_and_dependencies_by_population_density

**

**Pension reform, art, ads, jokes,cathedrals,DNA metaphor, thirst,

rich list versus Farage promises, follow the money.

AI scott

women only F1 the Academy

****

cycling rowing- mixed sex rowing teams?

***

In 2023, scientists uncovered the secret behind ancient Rome’s enduring architecture: self-healing concrete. Unlike today’s brittle blends, Roman builders packed their mix with special lime chunks. When water seeps into a crack, these lime particles react and crystallize—effectively sealing the damage. This 2,000-year-old “liquid stone” quietly repairs itself over time.

It’s why structures like the Pantheon and aqueducts still stand tall, while modern concrete often crumbles in just decades. The Romans weren’t just master builders—they were materials scientists far ahead of their time. Their forgotten genius is now helping shape the future.

Sources: Science Advances (2023), MIT Materials Lab, "Roman Concrete: The Hidden Science" by Marie Jackson

**

equality equity Rawls here

“Rawls took issue with the idea that happiness should even be the focus of a theory of justice. Justice, he thought, was about distributing the benefits and burdens of cooperation, and happiness was not really a direct product of cooperation. The problem is that people formulate their own life plans, according to various conceptions of the good, and the success of these plans is a major determinant of their achieved happiness levels. So happiness seems like the wrong thing for “society” to be concerned about, because it is too much under the control of individuals. Instead of looking at the output of people’s life plans, Rawls argued, a theory of justice should focus instead on the inputs, which is to say, the various liberties and goods that they require in order to carry out their plans.

Because of this, Rawls claimed that the “basis of expectations” in a theory of justice should be a list of what he called “primary goods,” including most importantly income and wealth.”

Sandel on Rawls https://sandel.scholars.harvard.edu/justice

*

**

Macron and the tissue https://x.com/BasedMillwall/status/1921568572788076865

Cocaine https://x.com/DrWoofAus/status/1922209232222355785

**

Autres temps, autres moeurs

L'expression "autres temps, autres mœurs" signifie que les comportements et les coutumes changent avec le temps. Elle indique que les gens se comportent différemment selon l'époque dans laquelle ils vivent.234 Cette expression provient d'une œuvre de La Bruyère, publiée en 1693.5 Elle est utilisée pour exprimer l'idée que les mœurs évoluent et que ce qui était acceptable ou courant dans le passé ne l'est plus nécessairement aujourd'hui.

***

76-year-old French movie star Gérard Depardieu was found guilty of sexual assault and given an 18-month suspended prison sentence

76-year-old actor Fanny Ardant (who starred alongside Depardieu in François Truffaut’s The Woman Next Door) testified in support of her friend Depardieu. She made her entrance in a long black dress and white collar, and delivered a passionate monologue about the art of acting. “I know we are here to search for the truth, but I would like to broaden the debate and say why Gérard Depardieu is such a great actor. He is a genius at giving his characters depth and richness, and a complexity with its share of contradiction, good and evil, light and shadow. Any genius carries in them something extravagant, rebellious and dangerous (…) If he is loved all over the world it is because everyone can recognise themselves in the characters he plays. (…) Yes, he has a big mouth, yes, he shouts obscenities, yes, he plays the fool. Without taking risks, one is no more an artist, one is just a servant.”

Ardant ended: “I know the world has changed, I know we now find intolerable what we used to tolerate and that institutions are here to transform society, but fear should not become the new morality.” The court’s president thanked Ardant for “this beautiful portrait of Gérard Depardieu” and, implacable, reminded the actor that “we are not here for morality purposes; we are here to apply the law. And to look at facts of sexual assaults.” Indeed.

**

Buffett on debt

https://x.com/PrefShares/status/1907785340703609302

**

Language

exploding deer

https://x.com/welshbollocks/status/1904090758077923822

**

**

Europe at night from Brilliant maps

Jane Jacobs

https://x.com/atlanticesque/status/1909605326279553304

**

Taleb on jobs

https://x.com/TalebWisdom/status/1911412707271549323

As Oscar Wilde said, there is only one thing worse than being employed…

Jansen chair

https://x.com/Rainmaker1973/status/1906579711628616082

**

Stewart Lee taxi

****

Von der Leyen https://x.com/business/status/1922567146124493081

**

**

This is the best concise writeup of how to build a relationship that I’ve ever seen

How Relationships Actually Work

53

2

I love this list of hobbies! I am slowly learning to cultivate my own habit of hobbies that bring me joy.

adult hobbies worth trying

377

1

for anyone at a loss for “what to do” for community building - pls read this actionable guide ♥️

Deeply Human Guide to Social Circles That Make You Feel Alive Again

72

3

I've been writing this post for 10 years.

Ultra-Processed Minds: The End of Deep Reading and What It Costs Us

81

2

A Truly life changing Article. I have been left questioning everything I know since.

How To Understand Things

302

3

Excellent analysis. I was halfway through writing one but this is better. Recommended!

Review: AI 2027

10

2

A lot of information packed into a lovely, lucid essay.

How To Think Slowly

20

1

Just great

21 observations from people watching

55

4

***

Bonhoeffer didn’t become brave in a prison cell.

He became brave in early mornings, hard choices, honest prayers, and costly decisions.

Martyrdom doesn’t begin at the noose.

It begins the moment you choose truth over popular.

And most of us get that chance every single day.

**

**

Think different-ly (Steve Jobs) Do different?

credit where credit is due- Aristotle

Emily is right. What we are dealing with in education isn’t simply a problem with technology brought about because of ChatGPT, but a crisis of purpose that has been long in the making.

****

from substack here by Sam Kriss

“I’m not a listener, because I’m basically allergic to podcasts in general. Podcasts make you stupid. When you listen to one you’re not really listening; you’re just bathing in simulated friendly chatter to convince the monkey part of your brain that you’re not a terminally friendless loser, which you are. (Consider: you could watch a film or a TV show or even some YouTube bullshit with a friend or romantic partner, but never a podcast. Podcasts are only consumed alone.) But despite not being a listener, I’m aware of what Rogan is. He has the world’s most popular podcast because he’s provided a welcoming environment for fringe weirdos, and people like to hear from fringe weirdos.”

“Who needs to be told that their own side is composed of faultless angels who have never done anything wrong in their lives, while their enemies are all bubbling in a black ooze out of the deepest chasms of Hell?”

(“War- what is it good for? Absolutely nothng, say it again”)

“What, at root, is the difference between these Israeli Überfrauen and the ungrateful toddlers of London and New York? ‘Young Israelis do not have the luxury of deciding whether they like war or develop grand ideas such as “war doesn’t solve anything.”’ He’s not wrong! If you’re a young, non-Haredi Israeli Jew and you decide that your moral convictions forbid you to join the army, the state can arrest you and send you to prison. Older Israelis don’t have that luxury either; they’re routinely arrested for criticising the army or mourning its victims. I think I prefer the decadent West.”

“but what he says is true: the debate over assisted dying has been a significant one in Britain. It’s one I’m interested in, because I’ve been on both sides in quick succession. I thought I was implacably against until earlier this year, when I had to watch my mother slowly dying in a hospital ward, and learned first-hand what unassisted dying really means. Maybe one day I’ll write about it.”

**

More Sam Kriss here

“Jacques Derrida’s critics accused him of being an ovist too, which he denied — sort of. “What interests me about eggs,” he said, “is not the egg as origin, the thought that the existence of things can be explained by reference to the egg, but the egg — if indeed we can speak of an egg — as a series of infinite deferrals of origin, already containing in an absent presence all that it originates. But how can I speak of eggs when, in order to arrive, to be heard, first my speech must be, from its very origin, already hatched, that is, it must already have erased the egg of its originless origin?” “

***

*****

BOZE

Reading about the insane numbers of books that ordinary working people used to read a hundred years ago feels like seeing pictures of the Pacific Ocean back when it teemed with whales. It’s honestly shocking what an intellectual culture we had. On the floors of tailoring factories, workers debated Marxism. Old couples with no formal education read to each other in Latin. Jane Austen and George Eliot were posthumous celebrities. In his book The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, Jonathan Rose tells how publishers had to “churn out school editions of Scott, Goldsmith, Cowper, Bacon, Pope and Byron” to keep up with demand from students. Traveling preachers introduced farmers to Milton and Tolstoy. Shakespeare reduced prisoners to tears. Up to the 1950s, coal miners built and maintained their own lending libraries. Unschooled Irishmen “somehow picked up a broad knowledge of etymology.” A young woman scared away suitors by revealing that she had read In Search of Lost Time three times. And again, folks a century ago weren’t inherently more intelligent than we are. I believe we could revive a culture, not of intellectuals but of autodidacts. People who are curious about the world, who are excited to learn and study together in community.

4 k

137

559

Stephen Fry versus Julie Burchill

jk by Julie Burchill

https://x.com/WingsScotland/status/1937065414300668278

**

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2025/03/27/solve-a-simpler-version-of-the-problem/

****

They are working on that, the problem is that so far the AI tends to make "predictions" rather than diagnoses:

https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/ai-connect-knee-xray-beer-drinking-shortcut-learning.html

"Using knee X-rays from the National Institutes of Health-funded Osteoarthritis Initiative, researchers demonstrated that AI models could “predict” unrelated and implausible traits, such as whether patients abstained from eating refried beans or drinking beer. While these predictions have no medical basis, the models achieved surprising levels of accuracy, revealing their ability to exploit subtle and unintended patterns in the data.

“While AI has the potential to transform medical imaging, we must be cautious,” said Peter L. Schilling, MD, MS, an orthopaedic surgeon at Dartmouth Health’s Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), who served as senior author on the study. “These models can see patterns humans cannot, but not all patterns they identify are meaningful or reliable. It’s crucial to recognize these risks to prevent misleading conclusions and ensure scientific integrity.”

google search

x new mosques being built

try clicking on this link- it takes you to…

this website

https://www.hearstnetworks.com/

not this one

****

Hassabis

cure all disease in 10 years

a coal mine- manufacturing jobs

French study- right happier than left

**

Reform vs globalisation

China WTO complaints

***

single stairway buildings from vox

“A fight about stairs could reshape American cities

By Rachel Cohen

Vox

13 min

May 8, 2025

A fight about stairs could reshape American cities

Reformers say tweaking construction rules can unleash affordable housing.

May 8, 2025, 10:00 AM UTC

Rachel Cohen is a policy correspondent for Vox covering social policy. She focuses on housing, schools, homelessness, child care, and abortion rights, and has been reporting on these issues for more than a decade.

Michael Eliason was an undergraduate studying architecture at Virginia Tech University when he went to live for a year in Germany. While interning in Freiburg in 2003, he worked on projects including apartment buildings four or five stories tall. After returning to the US and graduating, Eliason began his architecture career in Seattle, where he soon noticed that all the buildings he worked on kept getting “bigger and bigger.” It felt to him “like the exact opposite of my experience working in Germany.”

Reviewing his portfolio years later, Eliason noticed a stark contrast: All the US apartment buildings were massive and deep, while the European ones were relatively thin, featured different unit layout sizes, and welcomed significantly more natural light. He couldn’t quite articulate the significance yet, but he began to recognize that the German approach seemed to be the standard for urban housing throughout Europe, South America, and Asia.

In 2019, Eliason moved back to Germany with his wife and children. Before the first day at his new job, he and his soon-to-be boss discussed a 12-story housing project that had recently won a competition. Eliason was confused by the blueprint.

“There needs to be a second stair, right?” he asked. “Because in the US we would require a second stair for anything over three stories.” His new employer was puzzled by the question and explained that adding a second staircase would make the project financially infeasible.

“That was really the turning point for me,” Eliason told Vox. “The realization that the way we do housing in the US is radically, radically different from the rest of the world.”

He began sharing his observations on Twitter (since renamed X) and was joined by Stephen Smith, a New York-based urbanist writer who also frequently posted about architecture and real estate. Eliason, Smith, and a group of like-minded thinkers soon formed an informal coalition (and a group chat), introducing the concept of single-stair housing to American audiences. Ever since, they’ve been making the case that modernizing US building codes to permit this design could unleash more affordable housing nationwide — and their approach is winning even in the face of opponents who warn it’s unsafe.

In the United States, abundant forests and rapid westward expansion made wood the building material of choice. Unlike Europe, where dense cities and a long history of urban fires pushed builders toward brick and stone, Americans prioritized speed and cost — decisions that shaped building safety norms for generations.

“The US just had a lot of land, and so our fire protection measures ended up relying more on space,” explains Alex Horowitz, the project director of Pew Research Center’s housing policy initiative. This strategy of spacing out homes meant that compact building just wasn’t as necessary in America as it was elsewhere. Even today, multifamily housing makes up less than a third of America’s housing stock.

For centuries, most American apartment buildings had a single interior staircase. Then came a devastating Manhattan tenement fire in 1860. In response, the New York legislature passed a law requiring fire escapes on new residential buildings. This second exit safety philosophy became deeply rooted in American construction culture. As National Fire Protection Association engineer Val Zeevris put it, “In the United States in particular, free egress is just one of the fundamental concepts that we use as fire protection engineers. … So there’s that underlying concern that when there’s only one exit stair, we’re taking away people’s choice.”

Tragedies like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire only deepened this mindset. When a fire broke out on the upper floors of a 10-story factory in 1911, firefighters arrived quickly, but their ladders couldn’t reach the blaze. Dozens of workers — many of them young immigrant women — were trapped behind locked exit doors, a common anti-theft practice at the time. With no way out, some jumped from windows to escape the flames. In just 30 minutes, the fire killed 146 people.

Today, nearly all American cities require apartment buildings at least four stories tall to have two staircases, following standards set by the International Code Council (ICC), a nonprofit that develops building codes. This remains the case even as other modern safety features have made multifamily housing remarkably safe.

It typically costs less to rent in smaller buildings, yet such “missing middle” housing options — buildings with just two to 19 units — have become increasingly rare in the US, accounting for just a fifth of all housing units built since 2001.

Zoning restrictions, building code requirements, and pressure to maximize profits on expensive land help explain why. For advocates like Eliason and Smith, allowing single-stair construction for buildings up to six stories offers a practical solution.

According to research from Pew and the Center for Building North America (which Smith leads), adding a second stairway to a six-story apartment complex can require more than $300,000 in construction costs, while four-story buildings could face an estimated $258,000 increase. Eliminating this second staircase could cut costs by about 10 percent and encourage developers to build more desperately needed “missing middle” housing.

Beyond direct construction costs, the second stairway and its connecting corridor can also eat up a lot of space — taking up as much as 7 percent of a building’s floor area in small- and medium-sized buildings.

These constraints have real-world implications. Despite the influx of millennials to urban centers over the past 15 years, cities have struggled to retain families with children, sometimes due to limited housing options. Even in places with loosened zoning laws, most new construction favors studios, one- and two-bedroom apartments.

Single-stair buildings allow for more varied unit layouts, since the apartments can be arranged more freely around a central staircase. That flexibility could make it easier to build more family-friendly three- and four-bedroom units — now a rarity in 21st-century American construction.

The impact could be especially dramatic in dense cities, where many small lots remain undeveloped. Sean Jursnick, an architect in Colorado, found approximately 14,000 small lots in Denver where single-stair construction could make development more viable. Similar research identified 90,000 potential parcels in Portland, Oregon, and projected that 130,000 new homes could be added near transit in Boston.

Many housing policy ideas face resistance from existing homeowners, but single-stair advocates have found that their biggest opposition comes from fire safety officials. These leaders question the validity of international comparisons, and stress that decreased apartment fires in the US are largely due to safety protocols like second stairwells.

The International Association for Firefighters, representing unionized firefighters across the US and Canada, took a firm stance in their position statement this year:

While we understand and support the urgent need for additional affordable housing, [we] also believe that all housing must be safe housing. The removal of two exits—a critical safety design feature—is not an acceptable trade-off for additional housing.

Fire safety leaders are particularly frustrated by the new legislative approach to revising building codes, which involves giving less weight to third-party organizations like the International Code Council (ICC) and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). For decades, these groups have convened experts and industry leaders to develop safety recommendations that would then be codified into law.

“Most legislators don’t have the technical experience to evaluate these arguments,” Sean DeCrane, the IAFF’s assistant to the General President for Health and Safety, told me. “The [ICC] code process brings together technical experts to evaluate reports and consider trade-offs. How do you get the proper experts to all 50 states to have that discussion?”

But armed with research, persistent posting on social media, and mounting pressure from the housing crisis, single-stair advocates have continued to sway those in power. They argue that features like sprinklers make the design just as safe — and note that countries allowing single-stair buildings don’t report more fire deaths. Since fires are more common in single-family homes than in new apartments, they say current rules may actually steer people toward less safe housing. And for years, they add, US building codes have been dominated by single-family homebuilders, with little input from those focused on affordable apartments for families.

“We live in a democracy, and ultimately, politicians are the representatives of the people, not committee members at NFPA and the ICC,” Smith told Vox. “These experts make important contributions, but their organizations have their own politics. They are not neutral. They are not completely clear-minded engineers looking at facts without commercial interests.”

Eliason agrees, and suggests that opposition stems largely from comfort with the status quo. “Resistance to change is endemic to not just the fire industry but construction as a whole,” he said. “I think in the fire departments’ view, single-stair is such a radical departure from the way they’ve historically done things that they just don’t really understand the tradeoffs and benefits. There’s also this aspect of thinking that what we do in the US is superior to everywhere else.”

Despite the nationwide shift to double-stair requirements, several places have carved out exceptions. New York City first established its single-stairway allowance for mid-rise buildings in 1938, aiming to balance fire safety with the growing need for affordable housing on narrow lots, where adding a second staircase often wasn’t feasible. Seattle took its own approach in the 1970s, allowing single-stairway apartment buildings if they had safety features like an exterior stairway or a “smoke-proof tower.” Seattle’s code also later capped each single-stair building at six stories.

A handful of other jurisdictions have found their own middle ground: Honolulu adopted Seattle’s model in 2012, while Georgia, Vermont, and Puerto Rico all permit single-stairway buildings up to four stories tall.

Research led by Pew and the Center for Building in North America compared fire department statistics from Seattle and New York against the 100 US cities with the highest number of residential fires — and found no evidence of unique challenges or worse outcomes. This evidence, combined with the global prevalence of single-stair buildings, has fundamentally challenged the conversation around building codes in America.

Fire officials in other cities sometimes argue in favor of stricter building codes because they lack the fire safety resources of Seattle. But Smith pushes back, noting that many of these places don’t even allow four-story multifamily buildings — so the concern is moot, since those kinds of developments aren’t being built anyway. “Seattle is a very normal big city in America,” Smith added. “Seattle does not have a fire department head and shoulders above that of Jersey City, New Jersey, or Washington, DC.”

In fact, when policy experts approached Seattle fire officials about their markedly divergent building code, they were met with a surprising response: “‘I’m so sorry to tell you but to us this is just the code, this is how we do it,’” as Alex Armlovich, a housing analyst at the Niskanen Center think tank, recounts. “It was this emperor’s no clothes moment.” Seattle had been safely allowing single-stair buildings for decades without even considering it worth studying.

Smith sees a deeper logical flaw in how fire officials approach the issue: “The kind of logic that they’ll often use is, ‘We’re allowing things [in the code] that I already don’t like, so we can’t allow anything else that I don’t like.’ Whereas I look at it and say, ‘We should treat all buildings the same.’”

Fire safety experts and housing advocates are sharply divided over whether current evidence on safety is enough to justify revising the building codes.

Fire officials consistently argue that more research is essential. In September 2024, the National Fire Protection Association hosted an international symposium to explore the issue. (Smith was in attendance and gave a presentation.) Following the event, the group concluded there was a need for more detailed comparisons, for more granular and consistent data, and for more research into how people’s behavior, abilities, or circumstances affect fire risk. The NFPA announced plans to sponsor a research project through the Fire Protection Research Foundation to gather more information.

DeCrane of the IAFF was unimpressed with the symposium, calling it “very disappointing” and alleging it was “geared towards the proponents” of single-stair buildings. “It seemed that they wanted to come out with a process that appeased everybody,” he told me. “And we’re dealing with a life safety concern here, so we shouldn’t be appeasing everybody.”

The International Association of Fire Fighters has gone further, arguing that proponents haven’t shown how taller single-stair buildings deal with evacuation, fire operations, or resident safety.

The union outlined six specific research areas they believe need further study:

Simulations of evacuation times

Congestion in stairwells

Demographics of occupants

Stairway designs

Impact of smoke entering a stairwell

Movement patterns

Meanwhile, housing advocates and researchers argue that sufficient evidence already exists to move forward. Armlovich puts it bluntly: “We don’t have to take the NFPA people seriously on this because we have the entire world and NYC and Seattle.” He acknowledges there are still open questions around construction types that warrant further study. But he believes the existing evidence “is enough that I sleep soundly.”

Smith similarly recognizes there are some unresolved questions but considers them far less urgent than the IAFF suggests. “I definitely do have questions about how we would safely build a high-rise single-stair building. … I have some questions about the smoke control systems that are used in Europe, whether they really work that well or not,” he said. “But [American] standards for apartment buildings are already so intense...the alarm systems, the sprinklers — we have so much that they don’t have in Europe already.”

Smith notes a structural problem: In the US, building code research is often driven by private interests, unlike other countries where governments take the lead. “There’s no single-stair industry” to fund studies in America, he points out, unlike mass timber, which had single-family homebuilder backing.

The rapid momentum of the single-stair movement has surprised even its most ardent advocates.

To date, at least 15 states — including California, Minnesota, Montana, Tennessee, and Virginia — have passed laws or amended regulations to allow single-stair design in four- to six-story buildings, or are actively considering such changes. Most of these reforms have materialized just within the last two years. (Though some reformers have their eyes set long-term on greater heights — and indeed, legislation proposed in North Carolina this year would allow single-stair buildings up to eight stories — for now, the six-story push represents the path of least resistance.)

“It has been frankly a little faster than I expected,” Smith told me. “I think it’s because it’s a new topic that people did not realize was an issue. Building codes and standards can be so boring and dry. But what’s so interesting about single stairs is that it’s not just that it can be up to 10 percent of the cost of the building. The design implications are very exciting to people.”

The most “aggressive” state in adopting single-stair reform so far has been Tennessee, which passed legislation in 2024 to allow local jurisdictions to change their building codes. So far, at least three — Knoxville, Jackson, and Memphis — have done so.

“I guess success would be there’s no housing shortage, and we’ve developed super walkable neighborhoods with abundant housing and multigenerational housing.”

Minnesota took a different approach, investing over $200,000 into studying single-stair. A report on the findings is due by the end of the year.

Even in places that haven’t yet passed legislation, the conversation is advancing quickly. Steve Waldrip, senior housing adviser for Utah’s Republican Gov. Spencer Cox, told me that his team plans to make single-stair reform a priority in 2026 despite encountering initial resistance this year. “No one wants to be first, no one wants to be on the ledge, particularly when it comes to life safety issues,” he said. “But there’s a rising tide across the country that provides some security and safety in numbers.”

In Virginia, Democratic Delegate Adele McClure became a champion for single-stair reform after constituents from Northern Virginia approached her about the concept. She sponsored legislation last year to establish a study group of stakeholders to evaluate the idea, which passed unanimously.

While she initially encountered resistance from fire code officials, McClure found that including them in the process helped bring opponents on board. The experience also counters the notion that legislative approaches preclude technical expertise. For McClure, one of the biggest victories was simply getting people to consider an option that “hadn’t been considered at all prior.”

Even the ICC has shown some flexibility. The organization is likely to increase its single-stair height limit from three to four stories in its 2027 edition — a modest change, but significant given the conservatism of code development.

Housing advocates aren’t content to wait around. As Smith puts it, building codes are “a whole body of laws that have just traditionally flown totally under the radar, and as a result, [the field] developed some bad habits. I think those are sort of coming to light now.”

Twenty years from now, Eliason hopes their advocacy will have helped transform American cities. “I guess success would be there’s no housing shortage, and we’ve developed super walkable neighborhoods with abundant housing and multigenerational housing,” he said. “We need this broad array of housing types — social housing and market-rate housing and condos and co-ops. Single-stair, at least, helps to unlock some more opportunities.”

from vox

****

from The Sunday Times

Bella Ramsey, who stars in the post-apocalyptic television series The Last of Us, has said it is important separate gender awards are “preserved” to ensure female actors continue to gain recognition.

Ramsey, 21, who is non-binary but told The Louis Theroux Podcast “[I] don’t really care” about pronouns, did not take offence at being nominated for a Bafta and an Emmy in the female categories for HBO’s zombie drama.

Ramsey, who was born in Nottingham, said it was important to have male and female award categories to ensure women in the industry continue to be recognised

*

Matt Goodwin not pulling punches here to explain what he believes is responsible for the rise of Farage and reform.

(But why Farage????!!!!!)

“Consistently, everybody from Kemi Badenoch, who is leading the Tory party into oblivion, to the Financial Times, which has spent the last decade refusing to accept that many people might not want liberal globalism shoved down their throats, have described this revolt as “a protest” and Reform as “a protest party”.

“They are voting for the only thing that will also ensure they remain willing to support the welfare state and trust the system in the years ahead —a principle of ‘national preference’, whereby it is the hardworking, tax-paying, law-abiding majority that is prioritised and rewarded, not those who choose not to work, who do not pay tax, and who do not respect our laws.”

“they are voting for an alternative to this shocking sense of unfairness that now defines a country that has long considered fair-play a central aspect of its underlying identity. In this sense, they are voting for the thing they have always known and cherished, but which they now feel is being consistently violated and abused.”

“…vote for something other than the political, cultural, and media zeitgeist that has been imposed on this country in a highly authoritarian fashion ever since New Labour came to power nearly thirty years ago.

A pro-immigration, pro-globalisation, pro-liberalism, pro-Net Zero, pro-Woke, pro-trans, pro-London, pro-middle-class, pro-graduate consensus among the ruling class that chimes with the values of an elite minority, that at best represent no more than 15 per cent of the country, but angers and alienates the much larger forgotten majority.”

“a vote for an alternative to everything that Blair and pretty much everybody who has followed him into Number 10 Downing Street ever since, whether on the Left or Right, imposed on the country.

A big blob of social liberalism and technocratic progressivism mixed with an unfettered celebration of globalisation, identity politics, open borders, mass uncontrolled immigration, and universal liberalism, all of which has not only been backed up with authoritarian overreach (hate laws, non-crime incidents, expanded taboos, and concept creep to try and control and minimise dissent) but has also eroded the once distinctive foundations of this country and left its people deeply demoralised.

“It should be remembered, after-all, that the tendency to view populist parties merely as “protest parties”, first emerged in the 1980s and the 1990s, when scholars across Europe were struggling and largely failing to explain the first significant wave of public support for populist outsiders in post-war Europe.

It was only when these populist outsiders, from the French National Front to the Northern League in Italy and the Freedom Party of Austria, turned out to be far more durable and successful that the mainly left-wing scholars who studied them were forced to concede their voters might have clear and coherent motives of their own.”

from Matt Goodwin

**

Water Boards take on debt to pay CEOs and shareholders- who pays? Nationalize them again!!!!!!

**

French wine scam

“Cafes in tourist areas of Paris have been caught covertly pouring cheap wine in place of the premium glasses paid for by diners.

An investigation by Le Parisien newspaper found that wine fraud is rife in the French capital, with tourists often being the victims.

The outlet claims cafes are replacing fancy wines with budget alternatives. They discovered the fraud when sending two sommeliers to taste out the deception while pretending to be tourists.”

Of the wine ordered by the glass, investigators said that a pour of chablis or sancerre at around €9 (£7.65) was substituted for a sauvignon, the cheapest wine on the menu at around €5 (£4.25).

One of the undercover sommeliers, wine merchant Marina Giuberti, found a €7.50 sancerre had been replaced by a cheaper sauvignon priced at €5.60, but she was charged the higher rate.

human skin as leather

Steve QJ on women

blood

cycling Mikey

Learned helplessness

Reilly defends dancing not the person- the comment

what species is the fetus

perspective hot shower

terrorist subtitles

DNA how complex?

age of Viking DNA

misdirection https://x.com/Rainmaker1973/status/1917820762808885309

**

*Hanson songs overcoming bias

*

songs both sides now

Unchained Melody, Bobby Hatfield

the killing moon echo and the bunnymen

Mazzy star fade into you here

The killers Mr Brightside

**

ear muscle https://x.com/Rainmaker1973/status/1917822543160905761

‘Another said they were particularly aggrieved that the words appeared a critique of Starmer himself. “It looks like he is attacking Keir who has only just said climate action was in the DNA of the government.” ‘

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/apr/30/downing-street-forces-tony-blair-to-row-back-from-net-zero-strategy-criticism

Tony Blair Guardian

**

"Preoccupation with efficacy is the main obstacle to a poetic, noble, elegant, robust, and heroic life." - Nassim Nicholas Taleb in The Bed of Procrustes

**

Finding a job

*

More Wilfred Reilly

Mayfair enclosures

average, median

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_British_billionaires_by_net_worth

https://sites.stat.columbia.edu/gelman/research/unpublished/graphics_bd.pdf

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/architecture_cathedral_01.shtml

****

**

great list here

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2009/05/24/handy_statistic/

list of recommends https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/blogs-i-read/

Wells Cathedral

“700 years later, it is safe to say that these measures have been successful in preserving the tower for posterity. The cathedral boasts some of the finest medieval stained glass to be found in England which, miraculously, survived the Reformation and the Civil War. The 'Jesse' or 'Golden Window' dates back to 1340 and, thanks to its height, avoided the stones of the mob. The window traces the ancestry of Christ through Mary to Jesse, the father of King David, in the shape of a genealogical tree.”

from bbc history

*

Aaron Robotham · SotpodenrsM5h9rg2869a2: 40 fm133a ta1iatf37l5cll8f0ft29m21hh ·

Sometimes I worry about normal human/computer answers to captchas... Like here, the green region I think we'd agree with, but I know the square with the orange question mark definitely contains a bike, we just can't see it. So the Bayesian in me says "yes", then the normal human says "no", but I'm not sure how dumb or smart the computer might be

**

sayings that don’t exist

from

**

French pension reform

““I have worked since student jobs at 16 and began my working career aged 21 and I haven’t stopped since. The reform has hit our generation because we thought we were nearer retirement than we are and at the same time all we hear is that our pensions will also be less.”

from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/apr/29/disgruntled-french-workers-encouraged-to-arrive-late-in-protest-over-pension-age-rise

Bayrou abuse school https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvgp8kd7x18o

*

Cultural

Nick Hornby here

https://www.thebeliever.net/stuff-ive-been-reading-winter-2024/

“All That Glitters is the story of Whitfield’s relationship with Philbrick, from the time they studied together at Goldsmiths in London until the time of Philbrick’s disappearance, when it all got to be too much for him—he had told too many lies, promised too many things to too many people, owed too much money. And yet all his crimes seem to be a quite straightforward consequence of the way the contemporary art market operates: borderline criminality is baked in.

Here is how Philbrick and Whitfield operated. Walking home one evening, Philbrick spots what is now known to everyone as “a Banksy,” a piece of street art on a pair of metal doors. It depicts a rat wearing a baseball cap and carrying a beatbox. He sends a photo to Whitfield, who joins him at the site, and they plan what to do—because, of course, something has to be done. You can’t just leave it there for the enjoyment or indifference of passing foot traffic. The next morning, Philbrick hears back from a London auction house, and his contact there tells him that the auction house would pay eighty grand for it. This is right at the beginning, before the beginning, even, of our protagonists’ careers as gallerists in the art world. They are both still students.

If Banksy’s rat belongs to anyone, apart from the public, then it belongs to the owners of the building, so Philbrick suggests they bung the building manager fifteen grand and pay to replace the doors. They don’t have the fifteen grand, of course, but that doesn’t seem to matter. A conversation with the night manager is unsatisfactory. They show him what they are interested in doing, but he won’t let them speak to his boss. And before they know it, the Banksy is gone and the doors are being replaced. Philbrick calls Whitfield. “They fucked us! The fuckers. They fucking fucked us, dude. The door. It’s fucking gone.” I am not sure that Philbrick and Whitfield were fucking fucked, really. The thing they wanted to steal was stolen by someone else, is all.

But this is a world full of thieves, chancers, con artists. An artist called Adam installs a glass divider in their gallery—that is his entire show. (“A previous show of his, in New York, consisted of a woman he hired from Craigslist to travel to the vicinity of the gallery twice a week. No one but the woman knew when or if she would be there.”) When the billionaire collector Marc Steinberg sent his business manager to do an audit of the art fund Philbrick ran for him, Philbrick had to reproduce one of the works of art, because he’d sold the original, and the money had been “transferred out of the fund.” Luckily, the artwork in question was a bunch of rubber welcome mats, so Philbrick sourced a hundred of the same ones from a hardware store and re-created the piece. He got away with it. The business manager “had no idea what the fuck he was looking at,” Philbrick said, chortling, but one has sympathy for the guy. Who can tell, really, which rubber welcome mats are phony and which are real?