Homelessness- Scott Alexander and Medicine hat

What proportion of homeless people are homeless for less than 48 hours? What proprtion don’t want to live in a house? What proportion have mental health and/or addiction problems?

Scott Alexander from Astral Codex Ten explores.

see also

“I’m not a pollution expert, but I’m a psychiatrist, and I’ve been involved in the involuntary commitment process. So when people say “we should do something about mentally ill homeless people”, I naturally tend towards thinking this is meaningless unless you specify what you want to do - something most of these people never get to."

“Okay, then can you just make it a crime to be mentally ill, and throw everyone in prison? According to NIMH, 22.7% of Americans have a mental illness, so that’s a lot of prisoners. “You know what I mean, psychotic homeless people in tents!” Okay, fine, can you make homelessness a crime? As of last month, yes you can! But before doing this, consider:

In San Francisco, the average wait time for a homeless shelter bed is 826 days. So people mostly don’t have the option to go to a homeless shelter. If you criminalize unsheltered homelessness, you’re criminalizing homelessness full stop; if someone can’t afford an apartment or hotel, they go to jail.

Most (?) homeless people are only homeless for a few weeks, and 80% of homeless people are homeless for less than a year. If someone was going to be homeless for a week, and instead you imprison them for a year, you’re not doing them or society any favors.

How long should prison sentences for homelessness be? Theft is a year, so if homelessness is more than that, it becomes rational for people to steal in order to make rent. And realistically it will take police years to arrest all of the tens of thousands of homeless people, so if a sentence is less than a year, then most homeless people will be on the street (and not in prison) most of the time, and you won’t get much homelessness reduction.

What’s your plan for when homeless people finish their prison sentence? Release them back onto the street, then immediately arrest them again (since there’s no way they can suddenly generate a house while in prison)? Connect them to social services in some magical way such that the social service will give them a house within 24 hours of them getting out of prison? If such magical social services exist, wouldn’t it be cheaper and more humane to invoke them before putting someone in prison?

all from here

1. My Replies To Broad Categories Of Objections

Many of you had strong feelings on this one. As usual, you were wrong.

The first broad category of response was people who got angry at me because they thought I was saying homelessness was unsolveable and we shouldn’t try and you’re a bad person if you’re trying.

That’s not what I’m saying! I’m saying that there are some options, and we should debate them, but people have to specify them first. “Be tough” is a vibe, not a plan.

Plans will have to navigate tradeoffs around potentially not working, potentially being too weak, potentially costing too much money, and potentially being too draconian. I would like to see what tradeoff people choose. I don’t think a proper response to being asked to show your work is “YOU SAID IT’S POSSIBLE TO BE TOO DRACONIAN, THAT MEANS YOU LOVE CRIME AND ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE CONVERSATION!”

At the end of this post, I’ll list some possible plans commenters mentioned. Some of them are decent. I’m happy to debate those plans, but so far the debate hasn’t risen beyond the level of “Well, I would BE REALLY TOUGH!”

The second broad category of response was people who have grand plans for how many new institutions to build and how big those institutions would be. This could be part of a solution, but not all of it.

Why hasn’t the legal system already sent disruptive homeless people to prison? Will those same reasons ensure that if you built bigger, shinier institutions, the legal system wouldn’t trivially send people to those ones either?

I think the main problem is that homeless people mostly commit frequent low-level crimes that police mostly don’t see and victims mostly don’t report. When victims do report them, prosecutors don’t want to spend $50,000 to have a big trial to put a homeless person in jail for 90 days for disturbing the peace or whatever.

People think that “asylums” solve this because you just have to prove that someone is mentally ill. But this is also hard (will police be walking around administering the PANSS to everyone they see in a tent?) and under the existing systems you have to prove some additional point about danger. Even with the recent Supreme Court Grant’s Pass decision, there are a hundred finicky laws and precedents determining who you can and can’t arrest and for how long. I would like to see whether your plan involves pretending these don’t exist, or a concerted campaign to bring each one to the Supreme Court and overturn them, or what.

Again, this isn’t an unsolveable problem, but the solutions involve more thought than just repeating “BUT I WOULD BE TOUGH AND NOT SOFT” one thousand times and talking about how many stories high your new institutions would be. I would like to know what people’s proposed solutions are so I can assess them.

The third broad category of response was people who objected that surely this problem is solvable, because other countries solve it. The past solved it! California c. 2020 is the only society that has this level of problem with homelessness. We need to be ambitious and believe in ourselves!

Okay, but other countries solve crime without mass incarceration. France/Germany/Britain have 20% the incarceration rate that we do. So why don’t we eliminate 80% of prisons and use handwave handwave welfare social services to handle the former inmates? Now conservatives will start mumbling about American exceptionalism blah blah blah.

Or consider high-speed rail. A decade or two ago, California voted to construct a world-class high-speed rail system linking the whole state. Conservatives warned this would be a horrible boondoggle. But cheap, high-quality high-speed rail is definitely doable. Japan does it! France does it! America created a 3000 mile Rockies-crossing Transcontinental Railroad in f**king 1869, don’t tell me we can’t do rail! You’re just a defeatist who thinks we can’t do things other countries do easily.

Still, the conservatives were right. California’s high-speed rail is absolutely a horrible boondoggle: the state put tens of billions of dollars into the project and still hasn’t even connected the first two cities in the completely-flat-and-empty Central Valley. It’s unclear if they ever will. The last company they hired to run the project gave up in disgust and moved to Africa because it was “less politically dysfunctional” (this is true!)

Is it possible to become the sort of state/country that can build world-class high speed rail networks, close 80% of prisons, and end visible street homelessness? Yes, obviously, other countries do this, you could become like them somehow. But you don’t do it through ground-level rail policy, prison policy, or homelessness policy directly. You start by becoming a totally different sort of country. I would like for us to be the sort of country that does all of these things, and I hope that my blog posts/donations/votes make this more likely. But I don’t think you can start by planning the gleaming high-tech rail system, before you’ve solved the fundamental problems that make it impossible.

I also don’t think we should wait until we’re a more functional state to solve this problem. But the fact that we have to solve it in spite of dysfunction means we might need to be creative rather than steal the solution Switzerland or somewhere uses.

(I once asked a Swiss person how their streets were so clean, and he answered “everyone here is rich”).

Also, other US cities don’t have long-term mental asylums or anti-camping laws, so how can you use “other US cities manage to do this” as support for those programs?

The fourth broad category of responses was people who thought that, if they just said BE TOUGH many times, God would appreciate their toughness enough to additionally solve all of their totally-non-toughness-related problems.

This is kind of a mean way of putting it. But I’m thinking of people who say things like “We’ll create great wraparound social services with enough beds for everyone…and if people don’t accept them, we’ll send them to prison for a thousand years! I am so tough!”

I admit the prison for a thousand years part is tough, but I’m confused how your toughness is supposed to get you the great social services, when even the non-tough people who focus entirely on social services can’t do this. In general, many of the “BE TOUGH” plans assume so much state capacity, that the state capacity alone would be enough to solve the problem even without the toughness. This is another reason I want to hear people’s plans! When they say “BE TOUGH” they often mean “Assume a magical solution, and have a little bit of toughness on the side”. Then the debate centers so completely on the toughness and whether it’s morally justified that the magic part gets left alone.

“My solution to climate change is to switch all power plants to fusion, make all industries carbon neutral, and replace all cars with superconducting levitating pods - and if anyone complains, I’ll hit them with a lead pipe!”

“Oh no, not the lead pipe, that’s too cruel!”

“Wrong, you’re just a big softie, lead pipes are completely justified in an emergency such as this one!”

The fifth broad category of responses was people who admitted that they didn’t have a plan, but thought they shouldn’t have to - that wasn’t their job. These people are certainly in good company:

Honestly, fentanyl costs literally pennies, and if legal issues weren't an issue and it was produced in bulk for the market, you could keep essentially any addict completely high / happy on $1 a day.

I'm a fan of the "wet houses" proposals. All the drugs you can take, for free, far away from city centers. You're going to average $500 a year vs the 100k a year, and some tiny percentage of them (roughly 10% going by AA figures) will actually get out of their addictions and go on to be productive citizens, whereas a large portion of those 10% people die today due to supply chain contamination and illegible dosing due to it being illegal.

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/highlights-from-the-comments-on-mentally/comments

Antipsychotics are very cheap (some well-regarded drugs like Abilify and Seroquel cost about ~$10 per month of pills). On the other hand, homeless people have very little money. So if you were going to do this, it would make sense for the government to give them away for free.

These drugs have many potentially serious side effects. But it’s not clear how much homeless people’s 5-minute monthly visits with a bored Medicaid doctor does to avert these side effects, over having some kind of pharmacist or advocate or social worker in the free distribution center giving helpful advice.

Like everything, I think this would only help around the edges - the fraction of homeless mentally ill people who drugs can help, who are willing to take the drugs, and who are prevented only by cost and bureaucracy. What percent is that? Low confidence guess 25%.

**

Merlot (apparently a Canadian psychiatrist?) on long-acting injectable antipsychotics:

Long acting injectable anti-psychotics are really effective and a huge breakthrough, though not a complete panacea. You need a patient to actually respond to them and tolerate them (not all do), and then there's some degree of experimenting to figure out how long you can go between doses without losing effectiveness, and there's variation for different drugs. "Every few months" is something I've basically never seen, but all the points above still stand for a once a month injection which is more realistic (at least with the commonly used injectables in Canada). They're also more expensive than pills which is not the biggest deal, but my understanding is the insurance bureaucracy the US deals with is a pretty big barrier. Missing a dose by a few days is generally fine, but if someone misses for an extended period of time you also have to re-titrate them up to a treatment dose again. There are some additional risks and challenges that come from them being an injectable but they're relatively minor. It can also be challenging to inject them into the muscle properly on a very fat individual, and they have a side effect of weight gain, but I'd say that becomes an issue in less than 5% of cases. But again, overall they are great, and they increase adherence and decrease rehospitalization.

The thing is you can't just handwave away how you get the person in the room for the injection every month. Even in jurisdictions like Canada where you don't have the legal barriers to bringing someone in to get their injection, you need to have available police resources and be able to find and ID the person, which is hit or miss. Using recreational drugs also lowers the effectiveness of the LAIAs (though potentially less than oral meds?), and of course there's lots of drug induced psychosis in non-schizophrenic homeless people, homeless people with brain injuries, etc. And then you still have a homeless person at the end that requires a bunch of supports, just a less psychotic one that's potentially easier to house. But they're a very useful tool, and I'd guess there's a lot of room to expand their use in the US, even if the impact the public notices is likely to be marginal.

**

Theodidactus (lawyer, see blog here) on prosecuting low level offenses:

I think one thing I'd like to expand on is the criminal component.

A lot of "draconian" solutions necessarily require the criminal law (because you get minimal returns out of suing homeless or very poor people). In the United States, this means you're activating a ludicrously inefficient system to deal with low-level problems. It might be satisfying to a person of a deontological bent that no theft go unpunished, but it's hardly optimal. A lot of "soft on crime" policies in my jurisdiction come from a place of simply not wanting to bother with the time and expense of punishing an instance of shoplifting.

See, prosecutors make "good deals" that include no jail time as a way to get people to admit their guilt and move the case along. If you don't make "good deals" and decide to be draconian, people will fight back: they'll insist on trials for stealing a bag of chips...and nobody actually wants that, because trials have a ton of process. When I get a shoplifting case, I demand security footage (if available). Just getting that to me from the store is often more costly for the store than the stolen bag of chips. If I went to *trial* on a shoplifting case, I'd probably win unless two witnesses appeared for a whole afternoon: the employee who caught the lifter and the cop who showed up when/if they were called. Losing an employee for an afternoon is already a decent amount of time and expense for a victim, to say nothing of the police/jury/judge/clerk resources that get spent. If the plan is to put someone in jail for 60-120 days for stealing a bag of chips, you've turned a case people would normally shrug and admit to into something that is as worth fighting about as a white collar credit card theft. If the plan is to put someone away for 5-10 years for their next instance of loitering because they haven't learned their lesson the previous 128 times, we've turned a low-level misdemeanor into the trial of the century.

Finally and probably most important to your point: the Supreme Court did recently rule that you can technically criminalize homelessness, but actually prosecuting the "crime" of homelessness might be onerous in the future, since there would be numerous active defenses, everything from "there were no shelters available" to the truly preposterous "oh gosh, this was a big misunderstanding, I was walking back to my house and then a dude came out of nowhere and beat me and threw me in a ditch and that's why i'm in this ditch at 3AM". Trouble is that even if your defense is truly preposterous, you get a trial...

[…]**

SubstackCommenter2048 (used to work with public defenders), on commitment hearings:

> an overworked public defender who has devoted 0.01 minutes of thought to this case

Hey, something I know a little bit about! I worked briefly with some of these overworked public defenders, doing the legwork of interviewing newly committed psych ward patients to assess their desire for legal representation. Here is what I learned:

1. A lot of these people are pretty shaken up by whatever episode landed them in the hospital and are okay to stick around for a while until they're back on their psych meds, back on their non-psych meds (a LOT of HIV, hepatitis, diabetes, etc. in this population), and any wounds are stitched up and starting to heal.

2. That's good, because that's exactly the same thing most of the doctors want, and they're willing to release the patients once they're stabilized.

3. In the minority of cases where a patient wants to leave earlier than that, many are patients whose reasons are not going to go over well at a hearing (e.g., "I need to get out of here before President Terminator Robot finds me", "I am the Red Dragon of Revelation that is called Satan"). You generally try to talk these people down, but sometimes it goes to a hearing.

4. Many of the rest actually just desperately want to get back on the street, usually because they really love specific drugs that they can't score on a psych ward, but sometimes, seemingly, because they just love being free from any restrictions on where they can sleep, shit, or fuck, even if it means endangering their health, their sanity, and their lives.

5. For the 3s and 4s, you either go in front of a judge or negotiate with the doctors to get the person released. You do your best to argue that either: a. Even if they're crazy (that's the technical term in common use), they do not present a risk to themselves or others, and/or b. Even if they DO present a danger to themselves or others, that's because they are drunk/high/just an asshole, not because of their mental illness. Sometimes you even believe that the argument is legally sound. On rare occasions, like if you have a really power-hungry or stupid psychiatrist on the ward, you may even find it morally sound. Almost always, the doctors really do have the patients' best interests as their primary goal, and they have dealt with the legal system long enough to know which battles aren't worth fighting.

6. This system means that very sick people are in and out of involuntary commitment every few months or even more often. In between, they wreak all sorts of havoc, on their own bodies and minds and on the world and people around them.

7. It's expensive to house someone on a psych ward; it's even more expensive to house a seriously mentally ill person in prison; but it's probably even more expensive than that in terms of social costs to let them wander around for months until the cops pick them up again for assaulting someone, taking a shit in the middle of the floor at a homeless shelter, walking in traffic, etc. Accordingly, I'm very much in favor of re-institutionalization for chronic cases, for some definition of chronic. I recognize that this would have lots of unfortunate consequences. I am convinced that it could be implemented such that it has many fewer unfortunate consequences than our current system.

***

TorontoLLB (works in Toronto mental health) on street living:

I have worked with guardianship and mental health in downtown Toronto for over a decade.

As long as it is an option to live on the street for free, lots of people will choose that option (or default to that option to avoid more difficult choices). Wherever they are permitted, encampment communities grow faster than Austin.

It does not take too long living on the street using drugs and drinking every day for someone to convert themselves into the category of intractably addicted and mentally ill.

I think Scott has started from the "intractably mentally ill" point and done a great job of discussing the tradeoffs and issues with coerced care options. This is where I worked and I agree.

But isn't the real issue that we have SO MANY MORE homeless and mental health issues and drug addictions than in prior decades?

I think the proper way to evaluate the benefit of making sleeping outside illegal is in how much it slows the current machine converting at risk people into lifelong mental health and addiction patients.

I support zero tolerance for encampments despite the obvious fact that many current mentally ill and vulnerable people will suffer under such a policy. I believe a much larger number of people will be forced to find a path other than setting up a tent and self-medicating.

from

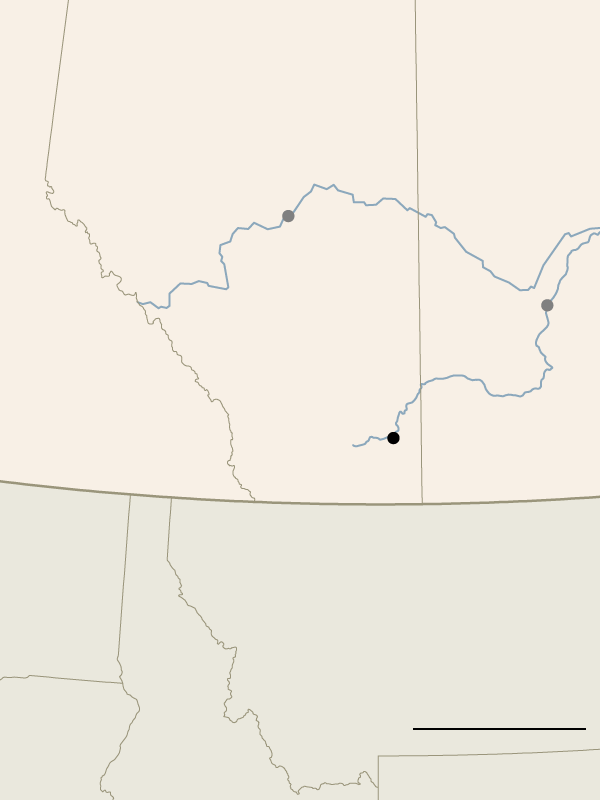

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/26/world/canada/homeless-canada-medicine-hat-housing-first.html

Medicine Hat, Alberta. A “housing first” strategy offers people homes without preconditions for sobriety and other self-improvement that keep many on the street elsewhere.

CreditAaron Vincent Elkaim for The New York Times

MEDICINE HAT, Alberta — Kurt Remple, a toothless, unemployed, struggling alcoholic in Medicine Hat, the curiously named prairie town in Alberta, is a success story of sorts. Five years ago, he was living under a bridge and surviving on free meals from charities.

Today, he lives in a small but tidy one-bedroom apartment in a stucco bungalow.

“It was November and it was getting cold when I met this worker at the Champion Center,” he said, referring to a local establishment that serves breakfast to the poor. “She said, ‘Come to my office and we’ll see if you can find a place.’ ”

Medicine Hat is on the leading edge of a countrywide effort to end homelessness through the “housing first” strategy, developed nearly 25 years ago by a Canadian in New York by which anyone identified as homeless is offered a home without preconditions for sobriety and other self-improvement that keep many people on the street elsewhere.

Alcoholic? Here’s a one-bedroom apartment where you can live — even if you’re still drinking. Drug addict? Here’s a studio with heat and hot water — even if you’re still getting high. Mentally ill? Here’s a place to feel safe and call your own — and where caseworkers can find you.

The theory is that only after people are in stable housing can they begin to address their other challenges.

A Canadian City Thrives on Gas, Like a ‘Wealthy Little Country’ FEB. 15, 2017

The strategy has been widely adopted in Europe and Australia. In the United States, it has found its most striking success in reducing homelessness among military veterans in cities like New Orleans, Salt Lake City and Phoenix. But no country has embraced the approach as firmly as Canada.

Jaime Rogers leads the Homeless and Housing Development Department of the Medicine Hat Community Housing Society. CreditAaron Vincent Elkaim for The New York Times

And nowhere in Canada has as much progress been made as in Medicine Hat, a small energy-rich city on the South Saskatchewan River. In November 2015, the city declared that it had succeeded in ending homelessness, bringing accolades and attention from all over the world.

But Medicine Hat’s claim points to the fuzzy logic of the problem: The end of homelessness is a state, not a moment. There will always be people who become homeless, and there will always be people who prefer to remain homeless, even in Medicine Hat.

“I like moving around — I can’t explain it,” said Gordon Thompson, a cheerful homeless man of 72, sitting in a Medicine Hat Salvation Army day room where clusters of people gather to pass the time and get a hot meal. He jokes with the caseworkers who come by imploring him to accept a home but stays instead in shelters or on the street, one among a hard-core cohort that shuns assistance.

As elsewhere in the world, Canada’s homelessness problem grew in recent decades as rising rents pushed the country’s most vulnerable citizens into the streets. The oil boom fed the real estate bubble in Alberta.

Calgary, the center of Alberta’s energy industry, had the worst homelessness in the province. In 2006, the province gave the city money to test the housing first approach, which had been pioneered more than a decade earlier by a Canadian psychologist, Sam Tsemberis, while he was working in New York.

With parallel projects popping up in British Columbia and Ontario, the Mental Health Commission of Canada got involved, lobbying for federal money to study the strategy. The commission started a clinical trial in five cities across Canada — Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Moncton — in which 2,200 homeless people with either mental illness or an addiction were randomly assigned to either housing first or treatment as usual.

By The New York Times

The results were startling, validating the housing first model and showing that the cost of housing the homeless was far less than the cost of the emergency services needed by the homeless while they were living on the street.

“The reduction in days in jail alone pays for the program,” said Jaime Rogers, a Medicine Hat housing official. She cited studies that said the average homeless person costs taxpayers 120,000 Canadian dollars a year, or $91,600, in services, while it costs just 18,000 Canadian dollars a year, or $13,740, to house someone and provide the necessary retention support.

That kind of evidence persuaded the conservative government of former Prime Minister Stephen Harper to pursue housing first as a national policy.

“This is where it went to a scale that I have not seen in any other country,” Dr. Tsemberis said in a telephone interview.

Under Canada’s subsequent Homeless Partnering Strategy, the federal government now distributes about 176 million Canadian dollars a year, or about $134 million, among 61 communities to fund services for the homeless. About 40 percent of that money must be spent on housing first interventions.

Seven Alberta cities — Calgary, Edmonton, Lethbridge, Grande Prairie, Red Deer, Wood Buffalo and Medicine Hat — formed a loose coalition and in 2007 each wrote its own 10-year plan to end homelessness. The province now spends more than 83 million Canadian dollars, or about $63 million, a year to carry out the plans, and came up with a 10-year plan of its own.

Photo

Hamid Vejvani, who has been homeless since 2009, at the Salvation Army’s hot meal program in Medicine Hat, Alberta, last month. CreditAaron Vincent Elkaim for The New York Times

Progress has been promising. In 2014, when Alberta conducted a “point in time” count — giving a snapshot of people who are homeless on a particular night — the total in the seven cities studied was 6,663. In 2016, the number had fallen nearly 20 percent, to 5,378.

Results in Medicine Hat were even more striking: The number of homeless counted fell by nearly half to 33 from 61. The number of participants in the housing first program, meanwhile, doubled to 120.

Medicine Hat leapt ahead, in part, because the problem is more manageable here. It is easier to deal with homelessness in a town of 63,000, where social workers know the names of almost everyone who is down and out. It is also easier when members from the agencies working on the problem are so few that they can sit down around a table.

But Medicine Hat has another advantage that could point the way for other cities: a centralized office that manages both housing stock and support programs. The Homeless and Housing Development Department of the Medicine Hat Community Housing Society is led by Ms. Rogers.

Recognizing that some people will always lose their homes, and with no national consensus of what “ending homelessness” means, Ms. Rogers and her team came up with their own definition: In Medicine Hat, it means connecting anyone identified as homeless with a caseworker and putting him or her on a waiting list for a housing program within 10 days.

That turned out to be a stroke of public relations genius, because when they reached their goal, word that Medicine Hat had “ended homelessness” ricocheted from Argentina to Germany to Japan. The once-skeptical mayor, whose office plays only a marginal role in the plan, has since given as many as 200 interviews on the subject to news media from all over the world.

Gordon Thompson has declined offers for an apartment and instead stays in shelters or on the street, one among a hard-core cohort that shuns assistance. CreditAaron Vincent Elkaim for The New York Times

The question, of course, is: How long do people remain homeless before being housed? Because of adequate federal and provincial funding and a good supply of local housing, few people in Medicine Hat remain truly homeless for more than a few months, Ms. Rogers said.

She added that it took time to help homeless people get their papers straightened out and arrange for government assistance. Then, they are offered at least three potential homes. Some prefer to wait in a shelter until they are happy with what is available.

Ms. Rogers said it cost less in the long run if the process was slow and deliberate because the goal is to house people permanently rather than rush them to unsuitable housing and have them return to the street.

Of course, a housing first strategy in larger cities becomes exponentially more complex, cautioned Dr. Stefan Kertesz, an associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, who has studied housing first challenges in the United States.

Only some major metropolitan centers are equipped with the leadership, manpower or structure necessary to coordinate a multiagency effort.

“Cities with tight housing markets need a very substantial amount of work, both in terms of front-line staff and organizational leadership, put toward recruiting landlords and even rehabbing buildings,” Dr. Kertesz said by email. “It means a major organizational undertaking with all pistons firing.”

Kurt Remple has a sparsely furnished apartment inside this stucco bungalow, obtained through the “housing first” approach. CreditAaron Vincent Elkaim for The New York Times

In Canada, there is now a move to define on a national scale what it means to end homelessness, providing a benchmark for success.

Alina Turner, a fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and one of the lead researchers pushing for a definition, said current programs should aim for “functional zero,” which recognizes that there will always be some people without homes.

Under the currently proposed definition, functional zero would mean a 90 percent decrease in people experiencing homelessness in a community.

“Housing is the easy part,” said Ms. Rogers, who acknowledged that by Dr. Turner’s definition, Medicine Hat still had a way to go. “Keeping them housed will always be the difficult part.”

Indeed, Mr. Remple, sitting in his sparsely furnished apartment, said this was the fifth place he had lived in during the five years since he connected with the housing first program.

“I kept taking in homeless friends,” he said blankly. “I’d have two or four people living and drinking and partying with me until I’d get evicted.”

Frustrating as such people might be, most eventually manage to settle down, social workers say. The stability of a home allows people to gradually address their problems.

Mr. Remple’s caseworker, Allysa Larmor, said he had been sober since January and seems determined to change his ways. She has helped mediate with his landlord and connect him with services like addiction counseling and a food bank, and she will soon start working with him on developing “meaningful daily activities” to fill the time that was once taken up drinking.

Correction: February 27, 2017

An earlier version of this article misspelled the given name of a former Canadian prime minister. He is Stephen Harper, not Steven. And an earlier version of a picture caption with this article misspelled the surname of an alcoholic who is taking part in the housing program. He is Kurt Remple, not Rempel.

Correction: February 27, 2017

An earlier version of this article misstated the equivalent United States dollar amount for 176 million Canadian dollars. It is $134 million, not $134.

Correction: March 7, 2017

An article on Wednesday about Canada’s “housing first” strategy to end homelessness, which provides housing without preconditions for sobriety or other self-improvement and is showing great promise in Medicine Hat, a small city in Alberta Province, erroneously attributed a distinction to Alberta. While the province conducted a “point in time” head count — a snapshot of people who are homeless on a particular night — in 2014, it was not the first such count in Canada. (A point-in-time count was done as far back as 2005, by Vancouver.)

https://www.reddit.com/r/medicinehat/comments/477jsq/has_medicine_hat_really_ended_homelessness/

Has Medicine Hat really ended homelessness? : medicinehat

www.reddit.com

I've been doing a lot of research regarding the homeless issue in Canada and I was curious if the statement that Medicine Hat has ended...