Kieran Egan- A Non Binary Approach to Education

The reviewer (unnamed at this stage- it’s an anonymous competition) doesn’t like the word imagination and I agree.

update - the reviewer won the competition, his name is Brandon Hendrickson and his site is

I also don’t like his choice- human so I’m going with Non-Binary

“The word falls on one side of a binary in education that goes “serious/unserious”, “challenging/easy”, “intellect/imagination”. This is ironic — and not in the good sense — because I think Egan’s approach would give us the most intellectually vibrant schooling we’ve ever had. Anyhow, that’s why, if you Google Egan, you’ll see the phrase “Imaginative Education” popping up.

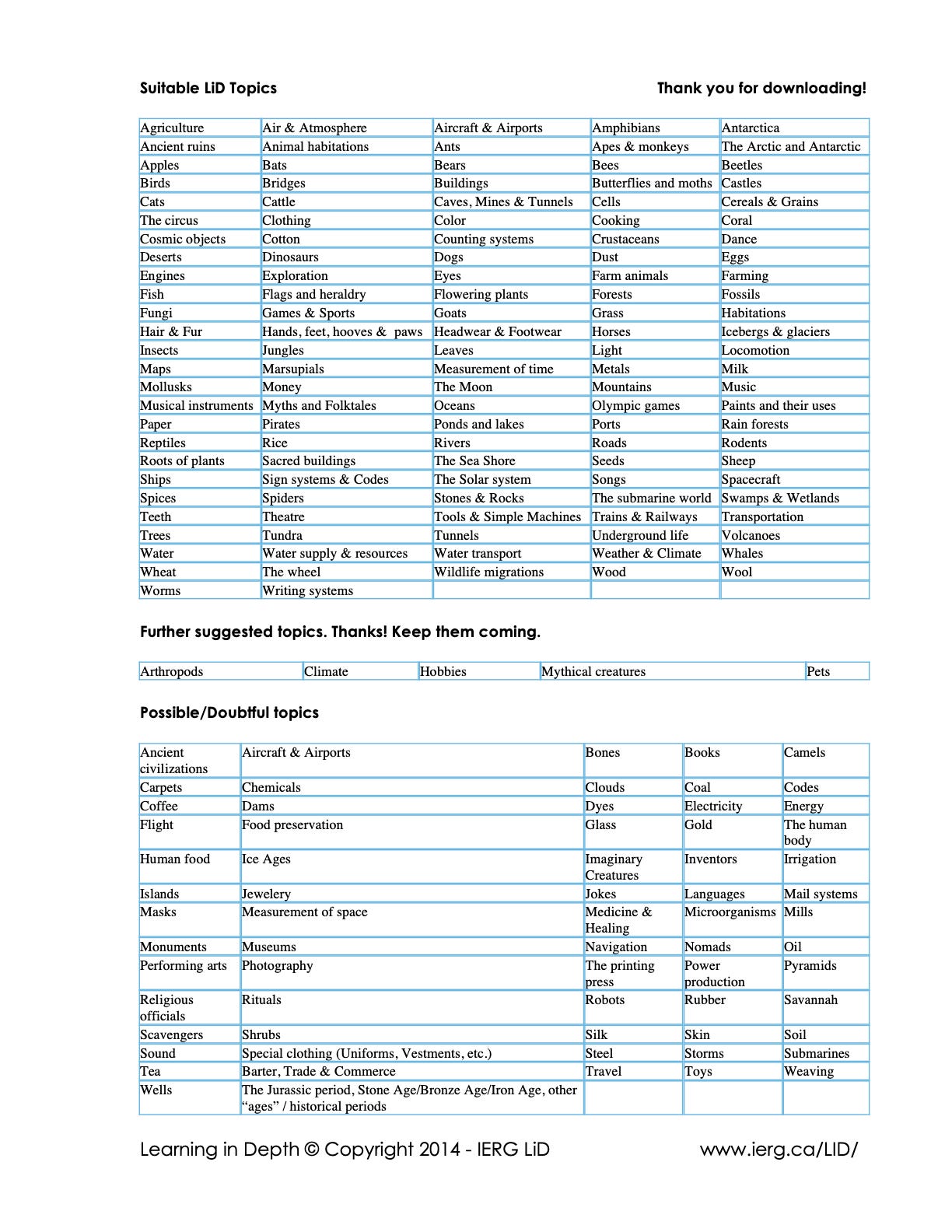

the list of 127 suitable topics (and 80-odd unsuitable topics) Egan and his collaborators worked hard to sift out:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pb0lOaBVn2z08WL0NOvA5c9rKwA5ZePM/view

bat-crap insane to you:

From

He was devoted to the dream that (as his obituary put it) “schooling could enrich the lives of children, enabling them to reach their full potential”.

“Education is one of the greatest consumers of public money in the Western world, and it employs a larger workforce than almost any other social agency.

“The goals of the education system – to enhance the competitiveness of nations and the self-fulfillment of citizens – are supposed to justify the immense investment of money and energy.

“School – that business of sitting at a desk among thirty or so others, being talked at, mostly boringly, and doing exercises, tests, and worksheets, mostly boring, for years and years and years – is the instrument designed to deliver these expensive benefits.

“Despite, or because, the vast expenditures of money and energy, finding anyone inside or outside the education system who is content with its performance is difficult.”

From trivial to rich: the trick

What could an intellectually rich elementary school curriculum look like, if we built it on kids’ cognitive strengths? He gives us one suggestion to help us do this: ask where each discipline came from in the first place. What was math before it was math, for example — or science before it was science?

irony, jokes

Poems here

As an uncontroversial example, think about temperature. We all begin as babies by perceiving two temperatures — hot and cold. Later, we add on intermediate categories — warm and cool. (Note that the human body is the assumed mid-point to temperature. Binaries often work like this; “big” and “small” mean “bigger or smaller than me”, “nasty” and “kind” mean “nastier or kinder than I am, except when my brother is really asking for it”, and so on.)

A good story (and an Egan-inspired elementary curriculum is, in a sense, nothing but good stories) will go further, and transform the binary.

An interesting aspect of Egan’s view of education is that he doesn’t seem to think we should push kids right to the “doing” phase. He wants to help kids cultivate an affective relationship with the world.

So the real question is what was history before it was history? His answer is myth.

in first grade we can tell kids the stories of the war of the Greek city-states against the Persian empire, and the slave uprising of Spartacus against the Romans. We can tell them about the plight of Jews in medieval Europe, and of the unsuccessful Sepoy Rebellion in India against the British. We can tell the stories of the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions, and about the Chinese Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. We can tell them the story of the escaped slave Harriet Tubman returning to the South to rescue her kinsmen, the story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges facing threats to integrate her elementary school, and the story of how the Mau-Mau uprising led to modern-day Kenya. We can tell the stories of Mexican-American union organizer Cesar Chavez.

Beyond binaries

First, teens are obsessed with gossip. The motivations of others — why did he do that? and what was he THINKING? — are hypothesized and talked to death.

Second, that they’re pulled toward idealism. Many feel a dissatisfaction with the world as it is, and feel a romantic urge to make it a better place. They’re often lured into simplistic beliefs that promise to help them do that.

Third, they love extremes: they want to find limits, and test them. Obviously, this can show up as risky behavior, but we can also see it in their love for the bizarre — note adolescents’ fascination in things like aliens, cryptids, and ghosts. (Egan loves pointing out that The Guinness Book of World Records is a perennial bestseller among kids at this age. How else would they find out who had the world’s longest fingernails?)

Fourth, they gravitate toward heroes — people who push the edges of those limits. By celebrating heroes, they can vicariously share in their transcendence. Look for the posts hanging up in a teenager’s bedroom to guess what boundaries they feel most hemmed in by: athletes push against physical limits; a death metal guitarist might push against authority and conventional morality. An activist or entrepreneur might push against our dulled morality or our sense of what’s possible.

When we teach the Cartesian coordinate system, students should meet Rene Descartes, the Calvinist French polymath who saw the possibility that math could decipher the world, if only we could unite algebra and geometry… and invented the xy-plane to do exactly that.

Who first discovered the things students learn about in science?

If you’re thinking “scientists”, you’re only partially right. Most of the big-picture ideas that we now think of as “science” were discovered before the word “scientist” was invented, or the discipline was professionalized. Frequently, they were hatched by true amateurs, working in their free time, hungry to unlock the secrets of nature. We can use gossip and heroes to spread their obsessions to students just as we taught math, but Egan points out two twists.

The first is that the content itself can take on heroic qualities: everything is impressive, when you look at it in a certain light. In an interview, Egan once said:

“My book is an attempt to show that, indeed, everything in the world is wonderful, but that schools are designed almost to disguise this slightly shameful fact. We represent the world to children as mostly known and rather dull. The opposite is the case: we are surrounded by mystery, and what we know is fascinating”.

The second twist is that science is a subject rich in extremes. Here Egan introduces a concept that we’ll see crop up again: “15-minute segments”. To help us fit as much wonder as possible into a school day, he suggests we supplement the usual school subjects with a few quick lessons. To infuse science with extremes, he suggests we add on three: “human & natural records”, “extremes of animals & plants”, and “cosmology”.

We also should add on another “15-minute segment” just to pump in as many biographies as possible, and from people who don’t always fit into the normal history curriculum. Call it “Brief Lives”, and throw in anyone who’s struggled to push some limit — Mary Wollstonecraft, Jesse Owen, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of the students’ great-aunts, whoever.

As students get older, this can transition to “People and Their Ideas”. Here, we’d focus less on the details of the person’s life, and use it as a backdrop to showing how meaningful some of history’s most important ideas could be. Think Aristotle and syllogisms, Edward Said and orientalism, Confucius and propriety, Cornel West and race, Buddha on the four noble truths, Muhammad and the five pillars, Karl Marx and communism, Adam Smith and the invisible hand, Thomas Hobbes and the state of nature, John Locke and natural rights, Jeremy Bentham and utilitarianism, Thomas Aquinas on the sacraments, Martin Luther on faith, Voltaire on the freedom of speech.

First, a mini-segment!

Intellectuals invented the academic disciplines to better pursue the life of the mind, but the disciplines can get in the way. Some of the most important intellectual discoveries that could help students are too big to fit into any of the disciplines. We need a place to introduce them plainly. Egan proposes another mini-segment — again, just 15 minutes a day, a few times a week — called “Metaknowledge”.

Q: Isn’t that already in the International Baccalaureate program?

Yes, he acknowledges that he’s borrowing from that! This segment would introduce ideas that would enrich student thinking across the disciplines: game theory, cognitive biases, systems thinking, Bayesian reasoning, epistemology, ethics, logic, cultural evolution, and so on.

And what does Egan say of the Flynn Effect?

Reviewer: So far as I know, he didn’t write about it — but I think the intriguing hypothesis is the same thing as the spread of Philosophic understanding! Philosophic understanding is all about the abstract, the general, the decontextualized. As low-level Philosophic understanding structures our society more and more, we have to practice elements of it, even outside school. This constant practice at Philosophic reasoning will probably show on an IQ test.

Alice: You haven’t mentioned much in the way of neurodiversity. Would an Egan school work well for a student with, say, ADHD?

Reviewer: As a person with ADHD who has two kids with ADHD and who teaches students with ADHD, the two words that pop into my head are: hot damn. And this seems to be the common opinion of Egan-fans around the world. For a lot of us, school is just so boring, and bringing back in emotional binaries and extremes and big ideas makes it not just bearable, but enjoyable.

Alice: That reminds me, I don’t remember you mentioning “attention” before, or a lot of other aspects of cognition that my educational research friends might spend their entire careers studying — I’m thinking things like “motivation”, “long-term memory”, “metacognition”, “creativity”, or “long-term thinking skills”. Is Egan silent on those?

Reviewer: He thought they were too small, and stole our focus from the bigger reality of how they all worked together. If you wanted a curriculum that maximized students’ metacognition, for example, you shouldn’t spend an inordinate amount of time training “metacognition” — you should aim to help them develop the five different kinds of understanding. Get the big picture right, and the details will follow.

Educated Mind came out in 1997, but he had built the fundamentals of his paradigm by the late Eighties. And since then, the cognitive sciences have swung toward embracing the power of the tools of what Egan’s dubbed “Somatic” and “Mythic” understanding — see Jonathan Gottschall for a popular account of the move toward narrative, Douglas Hofstadter for one on metaphor, Antonio Damasio for one on emotion, and Rebecca Schwarzlose for one on mental images.

Have you read any Joseph Henrich?

Alice: The aerospace-engineer-turned-Harvard-professor-of-human-evolution who’s helping reinvent how we understand anthropology, psychology, and economics? The author or The Secret of Our Success and The WEIRDest People in the World? I’m familiar with his work, yes.

Reviewer: Well, I think Egan is Joseph Henrich for education.

Reviewer: Both show how you can’t understand psychological differences among individuals just by looking at their genes, or at their immediate environment — you have to see what’s been happening in the hundreds and thousands of years of their ancestor’s cultural history. They also both point to the importance of “cognitive tools” gained through culture, argue that we’re smart because we connect up with others, and think that mimesis is at the very base of our cognition.

Further reading

http://www.educ.sfu.ca/kegan/A%20Brief%20Guide%20to%20LiD.pdf