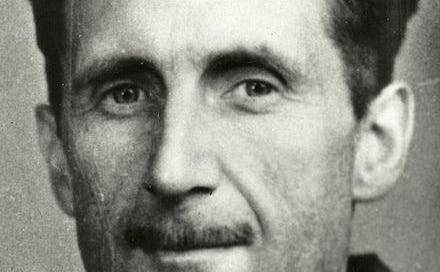

George Orwell

Reflections on Gandhi

Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases. In Gandhi's case the questions on feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity — by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power — and to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud? To give a definite answer one would have to study Gandhi's acts and writings in immense detail, for his whole life was a sort of pilgrimage in which every act was significant. But this partial autobiography, which ends in the nineteen-twenties, is strong evidence in his favor, all the more because it covers what he would have called the unregenerate part of his life and reminds one that inside the saint, or near-saint, there was a very shrewd, able person who could, if he had chosen, have been a brilliant success as a lawyer, an administrator or perhaps even a businessman.

At about the time when the autobiography first appeared I remember reading its opening chapters in the ill-printed pages of some Indian newspaper. They made a good impression on me, which Gandhi himself at that time did not. The things that one associated with him — home-spun cloth, “soul forces” and vegetarianism — were unappealing, and his medievalist program was obviously not viable in a backward, starving, over-populated country. It was also apparent that the British were making use of him, or thought they were making use of him. Strictly speaking, as a Nationalist, he was an enemy, but since in every crisis he would exert himself to prevent violence — which, from the British point of view, meant preventing any effective action whatever — he could be regarded as “our man”. In private this was sometimes cynically admitted. The attitude of the Indian millionaires was similar. Gandhi called upon them to repent, and naturally they preferred him to the Socialists and Communists who, given the chance, would actually have taken their money away. How reliable such calculations are in the long run is doubtful; as Gandhi himself says, “in the end deceivers deceive only themselves”; but at any rate the gentleness with which he was nearly always handled was due partly to the feeling that he was useful. The British Conservatives only became really angry with him when, as in 1942, he was in effect turning his non-violence against a different conqueror.

But I could see even then that the British officials who spoke of him with a mixture of amusement and disapproval also genuinely liked and admired him, after a fashion. Nobody ever suggested that he was corrupt, or ambitious in any vulgar way, or that anything he did was actuated by fear or malice. In judging a man like Gandhi one seems instinctively to apply high standards, so that some of his virtues have passed almost unnoticed. For instance, it is clear even from the autobiography that his natural physical courage was quite outstanding: the manner of his death was a later illustration of this, for a public man who attached any value to his own skin would have been more adequately guarded. Again, he seems to have been quite free from that maniacal suspiciousness which, as E. M. Forster rightly says in A Passage to India, is the besetting Indian vice, as hypocrisy is the British vice. Although no doubt he was shrewd enough in detecting dishonesty, he seems wherever possible to have believed that other people were acting in good faith and had a better nature through which they could be approached. And though he came of a poor middle-class family, started life rather unfavorably, and was probably of unimpressive physical appearance, he was not afflicted by envy or by the feeling of inferiority. Color feeling when he first met it in its worst form in South Africa, seems rather to have astonished him. Even when he was fighting what was in effect a color war, he did not think of people in terms of race or status. The governor of a province, a cotton millionaire, a half-starved Dravidian coolie, a British private soldier were all equally human beings, to be approached in much the same way. It is noticeable that even in the worst possible circumstances, as in South Africa when he was making himself unpopular as the champion of the Indian community, he did not lack European friends.

Written in short lengths for newspaper serialization, the autobiography is not a literary masterpiece, but it is the more impressive because of the commonplaceness of much of its material. It is well to be reminded that Gandhi started out with the normal ambitions of a young Indian student and only adopted his extremist opinions by degrees and, in some cases, rather unwillingly. There was a time, it is interesting to learn, when he wore a top hat, took dancing lessons, studied French and Latin, went up the Eiffel Tower and even tried to learn the violin — all this was the idea of assimilating European civilization as throughly as possible. He was not one of those saints who are marked out by their phenomenal piety from childhood onwards, nor one of the other kind who forsake the world after sensational debaucheries. He makes full confession of the misdeeds of his youth, but in fact there is not much to confess. As a frontispiece to the book there is a photograph of Gandhi's possessions at the time of his death. The whole outfit could be purchased for about 5 pounds***, and Gandhi's sins, at least his fleshly sins, would make the same sort of appearance if placed all in one heap. A few cigarettes, a few mouthfuls of meat, a few annas pilfered in childhood from the maidservant, two visits to a brothel (on each occasion he got away without “doing anything”), one narrowly escaped lapse with his landlady in Plymouth, one outburst of temper — that is about the whole collection. Almost from childhood onwards he had a deep earnestness, an attitude ethical rather than religious, but, until he was about thirty, no very definite sense of direction. His first entry into anything describable as public life was made by way of vegetarianism. Underneath his less ordinary qualities one feels all the time the solid middle-class businessmen who were his ancestors. One feels that even after he had abandoned personal ambition he must have been a resourceful, energetic lawyer and a hard-headed political organizer, careful in keeping down expenses, an adroit handler of committees and an indefatigable chaser of subscriptions. His character was an extraordinarily mixed one, but there was almost nothing in it that you can put your finger on and call bad, and I believe that even Gandhi's worst enemies would admit that he was an interesting and unusual man who enriched the world simply by being alive . Whether he was also a lovable man, and whether his teachings can have much for those who do not accept the religious beliefs on which they are founded, I have never felt fully certain.

Of late years it has been the fashion to talk about Gandhi as though he were not only sympathetic to the Western Left-wing movement, but were integrally part of it. Anarchists and pacifists, in particular, have claimed him for their own, noticing only that he was opposed to centralism and State violence and ignoring the other-worldly, anti-humanist tendency of his doctrines. But one should, I think, realize that Gandhi's teachings cannot be squared with the belief that Man is the measure of all things and that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have. They make sense only on the assumption that God exists and that the world of solid objects is an illusion to be escaped from. It is worth considering the disciplines which Gandhi imposed on himself and which — though he might not insist on every one of his followers observing every detail — he considered indispensable if one wanted to serve either God or humanity. First of all, no meat-eating, and if possible no animal food in any form. (Gandhi himself, for the sake of his health, had to compromise on milk, but seems to have felt this to be a backsliding.) No alcohol or tobacco, and no spices or condiments even of a vegetable kind, since food should be taken not for its own sake but solely in order to preserve one's strength. Secondly, if possible, no sexual intercourse. If sexual intercourse must happen, then it should be for the sole purpose of begetting children and presumably at long intervals. Gandhi himself, in his middle thirties, took the vow of brahmacharya, which means not only complete chastity but the elimination of sexual desire. This condition, it seems, is difficult to attain without a special diet and frequent fasting. One of the dangers of milk-drinking is that it is apt to arouse sexual desire. And finally — this is the cardinal point — for the seeker after goodness there must be no close friendships and no exclusive loves whatever.

Close friendships, Gandhi says, are dangerous, because “friends react on one another” and through loyalty to a friend one can be led into wrong-doing. This is unquestionably true. Moreover, if one is to love God, or to love humanity as a whole, one cannot give one's preference to any individual person. This again is true, and it marks the point at which the humanistic and the religious attitude cease to be reconcilable. To an ordinary human being, love means nothing if it does not mean loving some people more than others. The autobiography leaves it uncertain whether Gandhi behaved in an inconsiderate way to his wife and children, but at any rate it makes clear that on three occasions he was willing to let his wife or a child die rather than administer the animal food prescribed by the doctor. It is true that the threatened death never actually occurred, and also that Gandhi — with, one gathers, a good deal of moral pressure in the opposite direction — always gave the patient the choice of staying alive at the price of committing a sin: still, if the decision had been solely his own, he would have forbidden the animal food, whatever the risks might be. There must, he says, be some limit to what we will do in order to remain alive, and the limit is well on this side of chicken broth. This attitude is perhaps a noble one, but, in the sense which — I think — most people would give to the word, it is inhuman. The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one's love upon other human individuals. No doubt alcohol, tobacco, and so forth, are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid. There is an obvious retort to this, but one should be wary about making it. In this yogi-ridden age, it is too readily assumed that “non-attachment” is not only better than a full acceptance of earthly life, but that the ordinary man only rejects it because it is too difficult: in other words, that the average human being is a failed saint. It is doubtful whether this is true. Many people genuinely do not wish to be saints, and it is probable that some who achieve or aspire to sainthood have never felt much temptation to be human beings. If one could follow it to its psychological roots, one would, I believe, find that the main motive for “non-attachment” is a desire to escape from the pain of living, and above all from love, which, sexual or non-sexual, is hard work. But it is not necessary here to argue whether the other-worldly or the humanistic ideal is “higher”. The point is that they are incompatible. One must choose between God and Man, and all “radicals” and “progressives”, from the mildest Liberal to the most extreme Anarchist, have in effect chosen Man.

However, Gandhi's pacifism can be separated to some extent from his other teachings. Its motive was religious, but he claimed also for it that it was a definitive technique, a method, capable of producing desired political results. Gandhi's attitude was not that of most Western pacifists. Satyagraha, first evolved in South Africa, was a sort of non-violent warfare, a way of defeating the enemy without hurting him and without feeling or arousing hatred. It entailed such things as civil disobedience, strikes, lying down in front of railway trains, enduring police charges without running away and without hitting back, and the like. Gandhi objected to “passive resistance” as a translation of Satyagraha: in Gujarati, it seems, the word means “firmness in the truth”. In his early days Gandhi served as a stretcher-bearer on the British side in the Boer War, and he was prepared to do the same again in the war of 1914-18. Even after he had completely abjured violence he was honest enough to see that in war it is usually necessary to take sides. He did not — indeed, since his whole political life centred round a struggle for national independence, he could not — take the sterile and dishonest line of pretending that in every war both sides are exactly the same and it makes no difference who wins. Nor did he, like most Western pacifists, specialize in avoiding awkward questions. In relation to the late war, one question that every pacifist had a clear obligation to answer was: “What about the Jews? Are you prepared to see them exterminated? If not, how do you propose to save them without resorting to war?” I must say that I have never heard, from any Western pacifist, an honest answer to this question, though I have heard plenty of evasions, usually of the “you're another” type. But it so happens that Gandhi was asked a somewhat similar question in 1938 and that his answer is on record in Mr. Louis Fischer's Gandhi and Stalin. According to Mr. Fischer, Gandhi's view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler's violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly. One has the impression that this attitude staggered even so warm an admirer as Mr. Fischer, but Gandhi was merely being honest. If you are not prepared to take life, you must often be prepared for lives to be lost in some other way. When, in 1942, he urged non-violent resistance against a Japanese invasion, he was ready to admit that it might cost several million deaths.

At the same time there is reason to think that Gandhi, who after all was born in 1869, did not understand the nature of totalitarianism and saw everything in terms of his own struggle against the British government. The important point here is not so much that the British treated him forbearingly as that he was always able to command publicity. As can be seen from the phrase quoted above, he believed in “arousing the world”, which is only possible if the world gets a chance to hear what you are doing. It is difficult to see how Gandhi's methods could be applied in a country where opponents of the regime disappear in the middle of the night and are never heard of again. Without a free press and the right of assembly, it is impossible not merely to appeal to outside opinion, but to bring a mass movement into being, or even to make your intentions known to your adversary. Is there a Gandhi in Russia at this moment? And if there is, what is he accomplishing? The Russian masses could only practise civil disobedience if the same idea happened to occur to all of them simultaneously, and even then, to judge by the history of the Ukraine famine, it would make no difference. But let it be granted that non-violent resistance can be effective against one's own government, or against an occupying power: even so, how does one put it into practise internationally? Gandhi's various conflicting statements on the late war seem to show that he felt the difficulty of this. Applied to foreign politics, pacifism either stops being pacifist or becomes appeasement. Moreover the assumption, which served Gandhi so well in dealing with individuals, that all human beings are more or less approachable and will respond to a generous gesture, needs to be seriously questioned. It is not necessarily true, for example, when you are dealing with lunatics. Then the question becomes: Who is sane? Was Hitler sane? And is it not possible for one whole culture to be insane by the standards of another? And, so far as one can gauge the feelings of whole nations, is there any apparent connection between a generous deed and a friendly response? Is gratitude a factor in international politics?

These and kindred questions need discussion, and need it urgently, in the few years left to us before somebody presses the button and the rockets begin to fly. It seems doubtful whether civilization can stand another major war, and it is at least thinkable that the way out lies through non-violence. It is Gandhi's virtue that he would have been ready to give honest consideration to the kind of question that I have raised above; and, indeed, he probably did discuss most of these questions somewhere or other in his innumerable newspaper articles. One feels of him that there was much he did not understand, but not that there was anything that he was frightened of saying or thinking. I have never been able to feel much liking for Gandhi, but I do not feel sure that as a political thinker he was wrong in the main, nor do I believe that his life was a failure. It is curious that when he was assassinated, many of his warmest admirers exclaimed sorrowfully that he had lived just long enough to see his life work in ruins, because India was engaged in a civil war which had always been foreseen as one of the byproducts of the transfer of power. But it was not in trying to smooth down Hindu-Moslem rivalry that Gandhi had spent his life. His main political objective, the peaceful ending of British rule, had after all been attained. As usual the relevant facts cut across one another. On the other hand, the British did get out of India without fighting, and event which very few observers indeed would have predicted until about a year before it happened. On the other hand, this was done by a Labour government, and it is certain that a Conservative government, especially a government headed by Churchill, would have acted differently. But if, by 1945, there had grown up in Britain a large body of opinion sympathetic to Indian independence, how far was this due to Gandhi's personal influence? And if, as may happen, India and Britain finally settle down into a decent and friendly relationship, will this be partly because Gandhi, by keeping up his struggle obstinately and without hatred, disinfected the political air? That one even thinks of asking such questions indicates his stature. One may feel, as I do, a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi, one may reject the claims of sainthood made on his behalf (he never made any such claim himself, by the way), one may also reject sainthood as an ideal and therefore feel that Gandhi's basic aims were anti-human and reactionary: but regarded simply as a politician, and compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!

Questions

Look at Orwell’s opening sentence. “Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases.” The sheer brilliance (and quotability) of this sentence encourages the reader to accept it at face value but there are many possible criticisms of it. Which parts do you agree with?

What (or who) does Orwell mean by saints? Mother Theresa, Billy Graham, Pope John Paul? Lincoln, Washington, Martin Luther King? How should we “judge” these people? Should we “judge” these people? Who is/are “we”?

“They made a good impression on me, which Gandhi himself at that time did not.” Why not?

“The British were making use of him.” How?

“Hypocrisy is the British vice.” Another sweeping generalisation is thrust into the text. Is it true? What does he mean? Does he include himself in this appraisal?

“Close friendships, Gandhi says, are dangerous.” Why? Do you agree?

“An indefatigable chaser of subscriptions.” Perhaps Gandhi needed Youtube to really fulfil his destiny?

“But one should, I think, realize that Gandhi's teachings cannot be squared with the belief that Man is the measure of all things and that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have.” Can we infer Orwell’s beliefs from this sentence? Why does he mistrust Gandhi?

“Gandhi's view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which ‘would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler's violence’ .” What is Orwell’s view of this? (What was his role in the Spanish Civil War?) What is the point of being “aroused to violence” if you do not use violence against it?

“He urged non-violent resistance against a Japanese invasion, he was ready to admit that it might cost several million deaths.” If this had happened, would Gandhi have been “responsible” for the deaths? See Dr Sashi Thapoor on Churchill.

“On three occasions he was willing to let his wife or a child die rather than administer the animal food prescribed by the doctor.” This is logical if your actions on this earth are based on your belief in an after-life.

“Is there a Gandhi in Russia at this moment?” As relevant today as it was then.

“Applied to foreign politics, pacifism either stops being pacifist or becomes appeasement.” Why does Orwell admire an appeaser?

Les saints doivent toujours être jugés coupables jusqu'à ce que leur innocence soit prouvée, mais les tests qui doivent leur être appliqués ne sont pas, bien sûr, les mêmes dans tous les cas. Dans le cas de Gandhi, les questions que l'on est enclin à se poser sont les suivantes : dans quelle mesure Gandhi était-il mû par la vanité - par la conscience d'être un vieil homme humble et nu, assis sur un tapis de prière et secouant des empires par sa seule puissance spirituelle - et dans quelle mesure a-t-il compromis ses propres principes en entrant dans la politique, qui, de par sa nature, est inséparable de la coercition et de la fraude ? Pour donner une réponse définitive, il faudrait étudier les actes et les écrits de Gandhi dans un immense détail, car toute sa vie a été une sorte de pèlerinage dont chaque acte était significatif. Mais cette autobiographie partielle, qui s'achève dans les années vingt, est un témoignage fort en sa faveur, d'autant plus qu'elle couvre ce qu'il aurait appelé la partie non régénérée de sa vie et rappelle qu'à l'intérieur du saint, ou du quasi-saint, il y avait une personne très astucieuse et capable qui aurait pu, si elle l'avait choisi, réussir brillamment comme avocat, administrateur ou peut-être même homme d'affaires.

À peu près à l'époque où cette autobiographie a été publiée, je me souviens avoir lu ses premiers chapitres dans les pages mal imprimées d'un journal indien. Ils m'ont fait une bonne impression, ce qui n'était pas le cas de Gandhi lui-même à l'époque. Les choses que l'on associait à lui - le tissu filé à la main, les "forces de l'âme" et le végétarisme - étaient peu attrayantes, et son programme médiéviste n'était manifestement pas viable dans un pays arriéré, affamé et surpeuplé. Il était également évident que les Britanniques se servaient de lui, ou pensaient se servir de lui. À proprement parler, en tant que nationaliste, il était un ennemi, mais comme dans chaque crise il s'efforçait d'empêcher la violence - ce qui, du point de vue britannique, signifiait empêcher toute action efficace - il pouvait être considéré comme "notre homme". En privé, cela était parfois admis avec cynisme. L'attitude des millionnaires indiens était similaire. Gandhi les a appelés à se repentir, et ils l'ont naturellement préféré aux socialistes et aux communistes qui, s'ils en avaient eu l'occasion, auraient effectivement pris leur argent. On peut douter de la fiabilité de tels calculs à long terme ; comme Gandhi le dit lui-même, "en fin de compte, les trompeurs ne trompent qu'eux-mêmes" ; mais en tout cas, la douceur avec laquelle il était presque toujours traité était due en partie au sentiment qu'il était utile. Les conservateurs britanniques ne se sont vraiment mis en colère contre lui que lorsque, comme en 1942, il a en fait tourné sa non-violence contre un autre conquérant.

Mais je voyais déjà à l'époque que les fonctionnaires britanniques qui parlaient de lui avec un mélange d'amusement et de désapprobation l'aimaient et l'admiraient aussi sincèrement, d'une certaine manière. Personne n'a jamais suggéré qu'il était corrompu, ou ambitieux d'une manière vulgaire, ou que tout ce qu'il faisait était motivé par la peur ou la malveillance. En jugeant un homme comme Gandhi, on semble instinctivement appliquer des critères élevés, de sorte que certaines de ses vertus sont passées presque inaperçues. Par exemple, il est clair, même dans l'autobiographie, que son courage physique naturel était tout à fait exceptionnel : la manière dont il est mort en est une illustration ultérieure, car un homme public qui attachait de l'importance à sa propre peau aurait été mieux protégé. De plus, il semble avoir été tout à fait exempt de cette suspicion maniaque qui, comme E. M. Forster le dit à juste titre dans A Passage to India, est le vice indien le plus tenace, comme l'hypocrisie est le vice britannique. Bien qu'il ait sans doute été assez rusé pour détecter la malhonnêteté, il semble avoir cru, dans la mesure du possible, que les autres personnes étaient de bonne foi et avaient une meilleure nature par laquelle on pouvait les approcher. Et bien qu'il soit issu d'une famille pauvre de la classe moyenne, qu'il ait eu un début de vie plutôt défavorable et qu'il ait probablement eu une apparence physique peu impressionnante, il n'était pas affligé par l'envie ou par le sentiment d'infériorité. Le sentiment de couleur, lorsqu'il l'a rencontré pour la première fois dans sa pire forme en Afrique du Sud, semble plutôt l'avoir étonné. Même lorsqu'il combattait ce qui était en fait une guerre de couleur, il ne pensait pas aux gens en termes de race ou de statut. Le gouverneur d'une province, un millionnaire du coton, un coolie dravidien à moitié affamé, un simple soldat britannique étaient tous des êtres humains à part entière, à aborder de la même manière. Il est à noter que même dans les pires circonstances, comme en Afrique du Sud où il se rendait impopulaire en tant que champion de la communauté indienne, il ne manquait pas d'amis européens.

Rédigée en quelques pages pour être publiée en série dans les journaux, cette autobiographie n'est pas un chef-d'œuvre littéraire, mais elle est d'autant plus impressionnante que la plupart de ses éléments sont banals. Il est bon de rappeler que Gandhi a commencé avec les ambitions normales d'un jeune étudiant indien et n'a adopté ses opinions extrémistes que progressivement et, dans certains cas, plutôt involontairement. Il fut un temps, il est intéressant de l'apprendre, où il portait un chapeau haut de forme, prenait des cours de danse, étudiait le français et le latin, montait la Tour Eiffel et essayait même d'apprendre le violon - tout cela dans l'idée d'assimiler la civilisation européenne aussi complètement que possible. Il n'était pas un de ces saints qui se distinguent par une piété phénoménale dès l'enfance, ni un de ces autres qui abandonnent le monde après des débauches sensationnelles. Il confesse pleinement les méfaits de sa jeunesse, mais en fait il n'y a pas grand-chose à confesser. En frontispice du livre, on trouve une photographie des possessions de Gandhi au moment de sa mort. L'ensemble de ces biens pouvait être acheté pour environ 5 livres***, et les péchés de Gandhi, du moins ses péchés charnels, auraient la même apparence s'ils étaient tous placés dans un même tas. Quelques cigarettes, quelques bouchées de viande, quelques annas dérobées dans l'enfance à la servante, deux visites dans un bordel (à chaque fois, il s'en est sorti sans "rien faire"), une faute échappée de justesse avec sa logeuse à Plymouth, un accès de colère - voilà à peu près toute la collection. Presque dès l'enfance, il avait un profond sérieux, une attitude éthique plutôt que religieuse, mais, jusqu'à l'âge de trente ans, aucun sens très précis de la direction à prendre. Sa première entrée dans ce que l'on peut qualifier de vie publique s'est faite par le biais du végétarisme. Sous ses qualités moins ordinaires, on sent toujours les solides hommes d'affaires de la classe moyenne qui étaient ses ancêtres. On sent que même après avoir abandonné toute ambition personnelle, il a dû être un avocat plein de ressources et d'énergie et un organisateur politique acharné, attentif à limiter les dépenses, habile à gérer les comités et infatigable chasseur de souscriptions. Son caractère était extraordinairement varié, mais il n'y avait presque rien en lui que l'on puisse qualifier de mauvais, et je crois que même les pires ennemis de Gandhi admettraient qu'il était un homme intéressant et inhabituel qui a enrichi le monde simplement en vivant. Je n'ai jamais été tout à fait certain qu'il était également un homme aimable et que ses enseignements pouvaient apporter beaucoup à ceux qui n'acceptent pas les croyances religieuses sur lesquelles ils sont fondés.

Ces dernières années, il est de bon ton de parler de Gandhi comme s'il était non seulement sympathique au mouvement de gauche occidental, mais en faisait partie intégrante. Les anarchistes et les pacifistes, en particulier, se sont réclamés de lui, remarquant seulement qu'il était opposé au centralisme et à la violence d'État et ignorant la tendance anti-humaniste de ses doctrines. Mais il faut, je pense, se rendre compte que les enseignements de Gandhi ne peuvent être conciliés avec la croyance que l'homme est la mesure de toutes choses et que notre travail consiste à faire en sorte que la vie vaille la peine d'être vécue sur cette terre, qui est la seule que nous ayons. Ils n'ont de sens que si l'on suppose que Dieu existe et que le monde des objets solides est une illusion à laquelle il faut échapper. Il convient d'examiner les disciplines que Gandhi s'est imposées et qu'il considérait comme indispensables si l'on voulait servir Dieu ou l'humanité - même s'il n'insistait pas pour que chacun de ses disciples en observe tous les détails. Tout d'abord, ne pas manger de viande, et si possible aucune nourriture animale sous quelque forme que ce soit. (Gandhi lui-même, pour le bien de sa santé, a dû faire un compromis sur le lait, mais il semble avoir ressenti cela comme un retour en arrière). Pas d'alcool ni de tabac, pas d'épices ni de condiments, même d'origine végétale, car la nourriture ne doit pas être consommée pour elle-même mais uniquement pour préserver ses forces. Ensuite, si possible, pas de rapports sexuels. Si des rapports sexuels doivent avoir lieu, c'est dans le seul but d'engendrer des enfants, et vraisemblablement à de longs intervalles. Gandhi lui-même, au milieu de la trentaine, a fait le vœu de brahmacharya, ce qui signifie non seulement la chasteté totale mais aussi l'élimination du désir sexuel. Cette condition, semble-t-il, est difficile à atteindre sans un régime spécial et des jeûnes fréquents. L'un des dangers de la consommation de lait est qu'elle est susceptible d'éveiller le désir sexuel. Et enfin - c'est le point cardinal - pour le chercheur de bonté, il ne doit pas y avoir d'amitiés proches ni d'amours exclusives.

Les amitiés étroites, dit Gandhi, sont dangereuses, car "les amis réagissent les uns sur les autres" et, par loyauté envers un ami, on peut être amené à commettre des méfaits. C'est incontestablement vrai. De plus, si l'on veut aimer Dieu, ou aimer l'humanité dans son ensemble, on ne peut pas donner sa préférence à une personne en particulier. Cela aussi est vrai, et cela marque le point où l'attitude humaniste et l'attitude religieuse cessent d'être conciliables. Pour un être humain ordinaire, l'amour ne signifie rien s'il ne consiste pas à aimer certaines personnes plus que d'autres. L'autobiographie ne permet pas de savoir si Gandhi s'est comporté de manière inconsidérée avec sa femme et ses enfants, mais elle montre en tout cas qu'à trois reprises, il était prêt à laisser mourir sa femme ou un enfant plutôt que de lui administrer la nourriture animale prescrite par le médecin. Il est vrai que la menace de mort ne s'est jamais concrétisée et que Gandhi - avec,Il a toujours donné au patient le choix de rester en vie au prix de commettre un péché : pourtant, si la décision avait été la sienne, il aurait interdit la nourriture animale, quels qu'en soient les risques. Il doit y avoir, dit-il, une limite à ce que nous sommes prêts à faire pour rester en vie, et cette limite est bien de ce côté-ci du bouillon de poulet. Cette attitude est peut-être noble, mais, dans le sens que - je pense - la plupart des gens donneraient à ce mot, elle est inhumaine. L'essence de l'être humain, c'est de ne pas rechercher la perfection, d'être parfois prêt à commettre des péchés par loyauté, de ne pas pousser l'ascétisme jusqu'à rendre impossible toute relation amicale, et d'être prêt à la fin à être vaincu et brisé par la vie, ce qui est le prix inévitable pour attacher son amour à d'autres individus humains. Sans doute l'alcool, le tabac, etc. sont des choses qu'un saint doit éviter, mais la sainteté est aussi une chose que les êtres humains doivent éviter. Il y a une réplique évidente à cela, mais il faut être prudent avant de la faire. À notre époque où règnent les yogis, on suppose trop facilement que le "non-attachement" est non seulement meilleur qu'une acceptation totale de la vie terrestre, mais que l'homme ordinaire ne le rejette que parce qu'il est trop difficile : en d'autres termes, que l'être humain moyen est un saint raté. Il est douteux que cela soit vrai. Nombreux sont ceux qui, sincèrement, ne souhaitent pas être des saints, et il est probable que certains de ceux qui atteignent ou aspirent à la sainteté n'ont jamais été tentés d'être des êtres humains. Si l'on pouvait suivre le phénomène jusqu'à ses racines psychologiques, on constaterait, je crois, que le principal motif du "non-attachement" est le désir d'échapper à la douleur de la vie, et surtout à l'amour, qui, sexuel ou non, est un travail difficile. Mais il n'est pas nécessaire ici de discuter si l'idéal de l'autre monde ou l'idéal humaniste est "plus élevé". L'essentiel est qu'ils sont incompatibles. Il faut choisir entre Dieu et l'Homme, et tous les "radicaux" et "progressistes", du libéral le plus doux à l'anarchiste le plus extrême, ont en fait choisi l'Homme.

Cependant, le pacifisme de Gandhi peut être séparé dans une certaine mesure de ses autres enseignements. Son motif était religieux, mais il prétendait aussi qu'il s'agissait d'une technique définitive, d'une méthode, capable de produire les résultats politiques souhaités. L'attitude de Gandhi n'était pas celle de la plupart des pacifistes occidentaux. Le satyagraha, développé pour la première fois en Afrique du Sud, était une sorte de guerre non violente, une façon de vaincre l'ennemi sans le blesser et sans ressentir ou susciter la haine. Elle impliquait des actions telles que la désobéissance civile, les grèves, le fait de s'allonger devant les trains, de supporter les charges de la police sans s'enfuir et sans riposter, etc. Gandhi s'opposait à la "résistance passive" comme traduction de Satyagraha : en gujarati, semble-t-il, ce mot signifie "fermeté dans la vérité". À ses débuts, Gandhi a servi comme brancardier du côté britannique pendant la guerre des Boers, et il était prêt à faire de même pendant la guerre de 1914-18. Même après avoir complètement renoncé à la violence, il était assez honnête pour voir que, dans une guerre, il est généralement nécessaire de prendre parti. Il n'a pas - en fait, puisque toute sa vie politique était centrée sur la lutte pour l'indépendance nationale, il ne pouvait pas - adopté la ligne stérile et malhonnête qui consiste à prétendre que dans chaque guerre, les deux camps sont exactement les mêmes et que le vainqueur ne fait aucune différence. Il ne s'est pas non plus spécialisé, comme la plupart des pacifistes occidentaux, dans l'évitement des questions délicates. En ce qui concerne la dernière guerre, une question à laquelle tout pacifiste avait clairement l'obligation de répondre était la suivante : "Et les Juifs ? Êtes-vous prêt à les voir exterminés ? Si non, comment proposez-vous de les sauver sans recourir à la guerre ?". Je dois dire que je n'ai jamais entendu, de la part d'aucun pacifiste occidental, une réponse honnête à cette question, même si j'ai entendu beaucoup d'esquives, généralement du type "vous êtes un autre". Mais il se trouve qu'on a posé à Gandhi une question assez semblable en 1938 et que sa réponse est consignée dans l'ouvrage de M. Louis Fischer, Gandhi and Stalin. Selon M. Fischer, Gandhi était d'avis que les Juifs allemands devaient se suicider collectivement, ce qui "aurait éveillé le monde et le peuple allemand à la violence d'Hitler". Après la guerre, il s'est justifié : les Juifs avaient été tués de toute façon, et auraient pu tout aussi bien mourir de manière significative. On a l'impression que cette attitude a stupéfié même un admirateur aussi chaleureux que M. Fischer, mais Gandhi n'a fait qu'être honnête. Si vous n'êtes pas prêt à prendre la vie, vous devez souvent être prêt à ce que des vies soient perdues d'une autre manière. Lorsqu'en 1942, il a préconisé la résistance non violente à une invasion japonaise, il était prêt à admettre qu'elle pourrait coûter plusieurs millions de morts.

En même temps, il y a des raisons de penser que Gandhi, qui après tout est né en 1869, ne comprenait pas la nature du totalitarisme et voyait tout en termes de sa propre lutte contre le gouvernement britannique. Le point important ici n'est pas tant que les Britanniques l'aient traité avec indulgence que le fait qu'il ait toujours été capable d'attirer l'attention. Comme on peut le voir dans la phrase citée ci-dessus, il croyait qu'il fallait "éveiller le monde", ce qui n'est possible que si le monde a la possibilité d'entendre ce que vous faites. Il est difficile de voir comment les méthodes de Gandhi pourraient être appliquées dans un pays où les opposants au régime disparaissent au milieu de la nuit et on n'en entend plus jamais parler. Sans presse libre et sans droit de réunion, il est impossible non seulement de faire appel à l'opinion extérieure, mais aussi de faire naître un mouvement de masse, voire de faire connaître ses intentions à son adversaire. Y a-t-il un Gandhi en Russie en ce moment ? Et s'il y en a un, qu'accomplit-il ? Les masses russes ne pourraient pratiquer la désobéissance civile que si la même idée leur venait à tous simultanément, et même alors, à en juger par l'histoire de la famine en Ukraine, cela ne ferait aucune différence. Mais admettons que la résistance non violente puisse être efficace contre son propre gouvernement ou contre une puissance occupante : comment la mettre en pratique au niveau international ? Les diverses déclarations contradictoires de Gandhi sur la dernière guerre semblent montrer qu'il ressentait la difficulté de cette question. Appliqué à la politique étrangère, le pacifisme cesse d'être pacifiste ou devient un apaisement. De plus, l'hypothèse, qui a si bien servi Gandhi dans ses relations avec les individus, selon laquelle tous les êtres humains sont plus ou moins accessibles et répondront à un geste généreux, doit être sérieusement remise en question. Ce n'est pas nécessairement vrai, par exemple, lorsque l'on a affaire à des fous. La question se pose alors : Qui est sain d'esprit ? Hitler était-il sain d'esprit ? Et n'est-il pas possible qu'une culture entière soit folle selon les normes d'une autre ? Et, pour autant que l'on puisse évaluer les sentiments de nations entières, y a-t-il un lien apparent entre un acte généreux et une réponse amicale ? La gratitude est-elle un facteur dans la politique internationale ?

Ces questions et d'autres du même genre doivent être discutées, et de toute urgence, dans les quelques années qui nous restent avant que quelqu'un n'appuie sur le bouton et que les fusées ne commencent à voler. Il semble douteux que la civilisation puisse supporter une autre guerre majeure, et il est au moins envisageable que l'issue passe par la non-violence. C'est la vertu de Gandhi que d'avoir été prêt à considérer honnêtement le genre de questions que j'ai soulevées ci-dessus ; et, en effet, il a probablement abordé la plupart de ces questions d'une manière ou d'une autre dans ses innombrables articles de journaux. On sent chez lui qu'il y avait beaucoup de choses qu'il ne comprenait pas, mais pas qu'il y avait quelque chose qu'il avait peur de dire ou de penser. Je n'ai jamais pu éprouver une grande sympathie pour Gandhi, mais je ne suis pas sûr qu'en tant que penseur politique il se soit trompé dans l'ensemble, et je ne crois pas non plus que sa vie ait été un échec. Il est curieux qu'au moment de son assassinat, nombre de ses plus fervents admirateurs se soient exclamés avec tristesse qu'il avait vécu juste assez longtemps pour voir l'œuvre de sa vie en ruine, car l'Inde était engagée dans une guerre civile qui avait toujours été prévue comme l'un des sous-produits du transfert de pouvoir. Mais ce n'est pas en essayant d'aplanir la rivalité entre hindous et musulmans que Gandhi avait passé sa vie. Son principal objectif politique, la fin pacifique de la domination britannique, avait après tout été atteint. Comme toujours, les faits pertinents se recoupent. D'une part, les Britanniques ont quitté l'Inde sans combattre, un événement que très peu d'observateurs auraient pu prédire jusqu'à environ un an avant qu'il ne se produise. D'autre part, cela a été fait par un gouvernement travailliste, et il est certain qu'un gouvernement conservateur, en particulier un gouvernement dirigé par Churchill, aurait agi différemment. Mais si, en 1945, il s'était développé en Grande-Bretagne un vaste courant d'opinion favorable à l'indépendance de l'Inde, dans quelle mesure cela était-il dû à l'influence personnelle de Gandhi ? Et si, comme cela peut arriver, l'Inde et la Grande-Bretagne s'installent finalement dans une relation décente et amicale, sera-ce en partie parce que Gandhi, en poursuivant sa lutte avec obstination et sans haine, a désinfecté l'air politique ? Le fait que l'on pense même à poser de telles questions témoigne de sa stature. On peut ressentir, comme moi, une sorte de dégoût esthétique pour Gandhi, on peut rejeter les demandes de sainteté faites en son nom (il n'a d'ailleurs jamais fait de telles demandes lui-même), on peut aussi rejeter la sainteté en tant qu'idéal et donc penser que les objectifs fondamentaux de Gandhi étaient anti-humains et réactionnaires : mais considéré simplement comme un homme politique, et comparé aux autres grandes figures politiques de notre temps, quelle odeur propre il a réussi à laisser derrière lui !