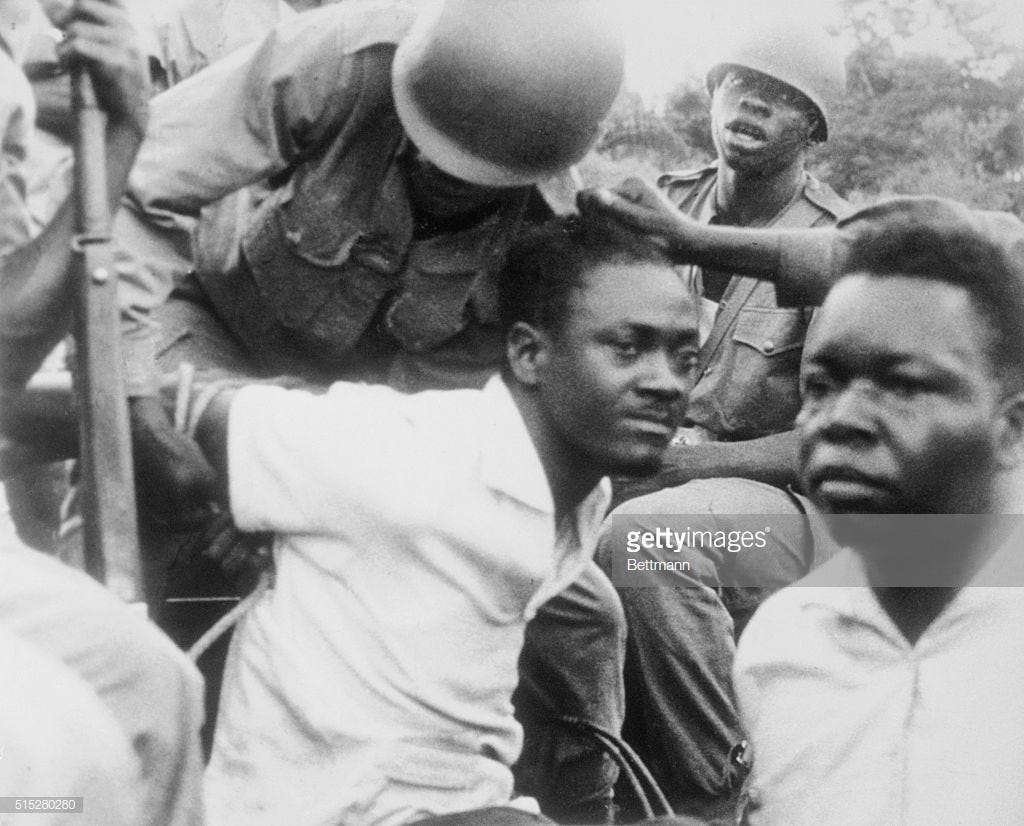

Patrice Lumumba

Kwame Nkrumah, Sekou Toure, Patrice Lumumba, Haile Selassie, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Amilcar Cabral, and Sylvanus Olympio

gold and armies Mansa Musa and Shaka Zulu

Nkrumah, who endured imprisonment in the fight for Ghana’s liberation from British rule, stated in his 1957 independence speech that “Our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa.”

Lumumba

In his last letter to his wife Lumumba writes:

“Neither brutal assaults, nor cruel mistreatment, nor torture have ever led me to beg for mercy, for I prefer to die with my head held high, unshakable faith, and the greatest confidence in the destiny of my country rather than live in slavery and contempt for sacred principles… Africa will write its own history and both north and south of the Sahara it will be a history full of glory and dignity…Do not weep for me, my companion; I know that my country, now suffering so much, ‘will be able to defend its independence and its freedom.”from

https://medium.com/the-daily-echo/profiles-in-courage-great-african-leaders-338279886c34

Patrice Lumumba on stooges, freedom, death, independence,

Afrika

Steve Biko, Emperor Haile Selassie, Patrice Lumumba, and Thomas Sankara. African Leaders of the Twentieth Century will complement courses in history and political science and serve as a useful collection for the general reader. Steve Biko, by Lindy Wilson Steve Biko inspired a generation of black South Africans to claim their true identity and refuse to be a part of their own oppression. This short biography shows how fundamental he was to the reawakening and transformation of South Africa in the second half of the twentieth century and just how relevant he remains. Emperor Haile Selassie, by Bereket Habte Selassie Emperor Haile Selassie was an iconic figure of the twentieth century, a progressive monarch who ruled Ethiopia from 1916 to 1974. The fascinating story of the emperor¹s life is also the story of modern Ethiopia. Patrice Lumumba, by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja Patrice Lumumba was a leader of the independence struggle in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Decades after his assassination, Lumumba remains one of the heroes of the twentieth-century Africanindependence movement. Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary, by Ernest Harsch Thomas Sankara, often called the African Che Guevara, was president of Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in Africa, until his assassination during the military coup that brought down his government. This is the first English-language book to tell the story of Sankara’s life and struggles.

“Kwame Nkrumah’s ideology can be described as a blend of Pan-Africanism, socialism, and non-alignment. He believed in the unity of African nations and the liberation of the African continent from colonialism and imperialism.”

https://medium.com/every-worker-is-a-soldier/who-was-kwame-nkrumah-understanding-his-influence-in-the-modern-day-a39c7ddd322

GHANA PUBLISHES 8 CONGO LETTERS; Reveals Nkrumah Messages to Lumumba ...

ACCRA, Ghana, Nov. 24 -- Eight letters from President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana to Patrice Lumumba, deposed Premier of the Congo, were published today in an effort to rebut accusations that

Black history or world history?

https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mcintosh.pdf

https://www.biography.com/tag/black-history

Who do we choose to remember? Millionaires, sportsmen, entertainers, politicians?

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/blackhistorystudies_samora-machel-patrice-lumumba-kwame-nkrumah-activity-7081233845383000064-ffpv/

Emmett Louis Till was born on July 25, 1941,

N Y times obituaries

The New York Times wrote after he died on Aug. 25, 1900. “His doctrines, however, were inspired by lofty aspirations, while the brilliancy of his thought and diction and the epigrammatic force of his writings commanded even the admiration of his most pronounced enemies, of which he had many.”

Those enemies included organized religion, especially Christianity, democracy, mediocrity, nationalism and women. Nietzsche railed against these and other adversaries on pages often densely packed with allusions, symbolism and language closer to romantic poetry than fusty metaphysics. Here is a sampling of his best-known writings:

Out of life’s school of war: What does not kill me, makes me stronger. — “Twilight of the Idols”

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you. — “Beyond Good and Evil”

God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console our selves, the most murderous of all murderers? — “The Gay Science”

Unlike many of his philosophical predecessors, Nietzsche did not argue for a specific weltanschauung, or worldview, even though his writings may suggest one. He distrusted any thinker who proposed a comprehensive system for interpreting the world, and he often wrote in a manner that allowed for multiple interpretations.

A critical examination of his work in The New York Times in 1910 explained his approach:

Nietzsche is not a philosopher in the strict and technical sense of the word. He has no system or consistent body of thought professing to explain all aspects of the universe. He does not expressly deal with epistemology, ontology or, indeed, with metaphysics in general. He concentrates himself on the moral and aesthetic aspects of things, on their “values,” as is now the custom to say, owing to Nietzsche himself, who introduced the term; and he does so with a literary force and artistic power of presentation which makes his writings specially stimulating and is really the cause of his comparative popularity.

The name Huey P. Newton can elicit cries of “hero” or “criminal,” and the space in between reflects the distance in racial perspectives that the United States has failed to bridge since Newton helped found the Black Panthers 50 years ago, when the civil rights struggle was moving beyond the South to black neighborhoods in the North and West.

Newton advocated armed self-defense in black communities, where the organization also provided social services. They would patrol the streets, guns drawn, turning them on drug dealers and police officers alike.

Expressing a willingness to defend oneself with weapons was hardly revolutionary. When Frederick Douglass was asked in 1850 what he believed to be the best response to the Fugitive Slave Act, he replied, “A good revolver.” And Malcolm X advocated the same.

The Black Panthers, which never grew beyond a few thousand members, tried to combine socialism and black nationalism. Its charter called for full employment, decent housing, and the end of police brutality.

Unlike black separatists, the Panthers welcomed all races and found wealthy liberals willing to give them money. But the group’s social programs — like a breakfast program for schoolchildren and clothing and food drives — came undone partly by the corruption of the leadership.

Historians have detailed its mistreatment of female members, extortion, drug dealing, embezzlement and murder. At least 19 Panthers were killed in shootouts with one another, the authorities or other black revolutionaries.

While “by any means necessary” became a mantra of the group, J. Edgar Hoover’s F.B.I. also did whatever possible to target the Panthers. As many members went off to prison and the group dwindled, Newton became a despotic and paranoid drug addict, wielding dictatorial powers with a small coterie, and knocking off anyone in his way.

While the Panthers’ time of influence ended quickly, Newton never escaped the organization. In 1980, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy. But he was shot to death on Aug. 22, 1989, in a crack cocaine deal gone bad. He was 47, a victim of the same streets he had once tried to make safe.

Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah were divided on what should happen once the British left. Gandhi, more an idealist than a realist, wanted an undivided nation; he chose to remain out of government.

The British negotiated with the Muslim League, led by Jinnah, who believed that a separate state was the only way to protect the rights of Muslims, who were a minority; and the (mostly Hindu) Indian National Congress, led by Nehru, who grudgingly went along with the British decision to divide India on the basis of religion.

Cyril Radcliffe, who had never been to Asia, arrived in India 36 days before the date of the partition to draw the lines to split one of world’s largest and most ethnically diverse countries. On Aug. 9, he finished drawing the map, but the British viceroy, his superior, kept it a secret. He didn’t want the British to be blamed for any ensuing violence. But it prolonged the uncertainty for millions and very likely increased the loss of life to come.

Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment” — a split second that reveals the larger truth of a situation — shaped modern street photography and set the stage for hundreds of photojournalists to bring the world into living rooms through magazines such as Life and Look. In 1947, he and Robert Capa helped create the photographer-owned cooperative photo agency Magnum.

“Those whom the gods love die young,” the ancient Greek dramatist Menander wrote. In a 1962 speech he gave by the sea in Newport, R.I., Mr. Kennedy’s father — prophetically for the son — sounded a related theme:

“I really don’t know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it is because in addition to the fact that the sea changes and the light changes, and ships change, it is because we all came from the sea. And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have, in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it, we are going back from whence we came.”

At 17, like many other Americans, Medgar Evers enlisted in the Army during World War II. A star athlete in high school, he participated in the Allied invasion of Europe, rising to the rank of sergeant before his honorable discharge in 1946.

But for Evers, who was born on this day in 1925 to an African-American farming family in Decatur, Miss., even the segregated Army was more welcoming than the Jim Crow South to which he returned after the war.

The racial injustice there rankled so much that he resolved to fight it, becoming the first field officer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Mississippi.

“Obviously not all white people are wealthy, and obviously many minorities are rich and powerful. Lots of white people are disadvantaged. But white privilege is something specific and different from the ordinary rising and falling of a free society. It’s the fact that simply by virtue of being a white person, of whatever socioeconomic status, you get the benefit of the doubt”.

Schools which teach pupils that “white privilege” is an uncontested fact are breaking the law, the women and equalities minister has said.

Addressing MPs during a Commons debate on Black History Month, Kemi Badenoch said the government does not want children being taught about “white privilege and their inherited racial guilt”.

“Any school which teaches these elements of political race theory as fact, or which promotes partisan political views such as defunding the police without offering a balanced treatment of opposing views, is breaking the law,” she said.

She added that schools have a statutory duty to remain politically impartial and should not openly support “the anti-capitalist Black Lives Matter group”.

https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mcintosh.pdf

https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality/transcript#t-1113210

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/07/dehumanizing-condescension-white-fragility/614146/

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government and authorized a payment of $20,000 (equivalent to $43,000 in 2019) to each former internee who was still alive when the act was passed. The legislation admitted that government actions were based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership."[31] The U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion (equivalent to $3,460,000,000 in 2019) in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been interned.[30][32]