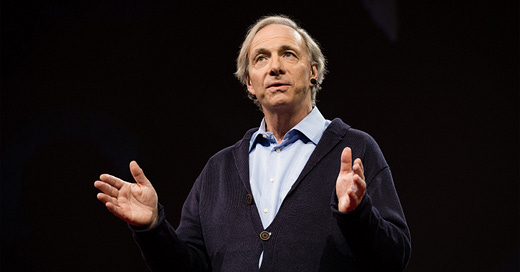

This is Aaron Swartz on Ray Dalio. http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/dalio

Ray Dalio writes:

"It is a fundamental law of nature that to evolve one has to push one’s limits, which is painful, in order to gain strength—whether it’s in the form of lifting weights, facing problems head-on, or in any other way. Nature gave us pain as a messaging device to tell us that we are approaching, or that we have exceeded, our limits in some way. At the same time, nature made the process of getting stronger require us to push our limits. Gaining strength is the adaptation process of the body and the mind to encountering one’s limits, which is painful. In other words, both pain and strength typically result from encountering one’s barriers. When we encounter pain, we are at an important juncture in our decision-making process."

(From wikipedia) In 2013, his company, Bridgewater, was listed as the largest hedge fund in the world. In 2020 Bloomberg ranked him the world's 79th-wealthiest person.[8] Dalio is the author of the 2017 book Principles: Life & Work, about corporate management and investment philosophy.

He told his children, “you can have anything you want in life but you can’t have everything you want". Do you agree? Is life different for the children of a billionaire?

Watch this Tedtalk from 3.51 to 7.06 https://www.ted.com/talks/ray_dalio_how_to_build_a_company_where_the_best_ideas_win

What does he mean by Emerging Countries?

What is a Debt crisis?

What is a Bear market (opposite of a bull market) ? Have you seen this statue? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charging_Bull

Why did he think Mexico would default?

Why was he asked to testify to Congress?

“I know how markets work”. If he did (and he did) why did he lose all his money?

Humility balances audacity”. Do you agree?

Further study:

If students are interested in more, they can read about George Soros using the ERM to make a billion pounds

https://www.thebalance.com/black-wednesday-george-soros-bet-against-britain-1978944

and the Wolf of Wall Street talking about gamestop.

This is interesting but some students find Jordan’s accent difficult to understand.

Ray Dalio écrit :

"C'est une loi fondamentale de la nature que pour évoluer, il faut repousser ses limites, ce qui est douloureux, afin de gagner en force - que ce soit sous la forme de soulever des poids, d'affronter les problèmes de front, ou de toute autre manière. La nature nous a donné la douleur comme moyen de communication pour nous indiquer que nous approchons de nos limites ou que nous les avons dépassées d'une manière ou d'une autre. En même temps, la nature a fait en sorte que le processus de renforcement nous oblige à repousser nos limites. L'acquisition de la force est le processus d'adaptation du corps et de l'esprit à la rencontre de ses limites, ce qui est douloureux. En d'autres termes, la douleur et la force résultent toutes deux de la rencontre avec les obstacles. Lorsque nous rencontrons la douleur, nous nous trouvons à un moment important de notre processus de décision."

D'après wikipedia, En 2013, sa société, Bridgewater, a été répertoriée comme le plus grand fonds spéculatif au monde. En 2020, Bloomberg l'a classé comme la 79e personne la plus riche du monde[8] Dalio est l'auteur du livre Principles : Life & Work, sur la gestion d'entreprise et la philosophie d'investissement.

Il a dit à ses enfants, "vous pouvez avoir tout ce que vous voulez dans la vie, mais vous ne pouvez pas avoir tout ce que vous voulez". Êtes-vous d'accord ? La vie est-elle différente pour les enfants d'un milliardaire ?

Regardez ce Tedtalk de 3.51 à 7.06 https://www.ted.com/talks/ray_dalio_how_to_build_a_company_where_the_best_ideas_win

Qu'entend-il par "pays émergents" ?

Qu'est-ce qu'une crise de la dette ?

Qu'est-ce qu'un marché baissier (opposé à un marché haussier) ? Avez-vous vu cette statue ? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charging_Bull

Pourquoi pensait-il que le Mexique ferait défaut ?

Pourquoi lui a-t-on demandé de témoigner devant le Congrès ?

"Je sais comment les marchés fonctionnent". Si c'est le cas (et c'est le cas), pourquoi a-t-il perdu tout son argent ?

L'humilité équilibre l'audace". Êtes-vous d'accord ?

Une étude plus approfondie :

Si les élèves souhaitent aller plus loin, ils peuvent lire l'article sur George Soros qui a utilisé le MCE pour gagner un milliard de livres sterling

https://www.thebalance.com/black-wednesday-george-soros-bet-against-britain-1978944

Dalio’s Principles

When I say that these are my principles, I don’t mean that in a possessive or egotistical way. I just mean that they are explanations of what I personally believe. I believe that the people I work with and care about must think for themselves. I set these principles out and explained the logic behind them so that we can together explore their merits and stress test them. While I am confident that these principles work well because I have thought hard about them, they have worked well for me for many years, and they have stood up to the scrutiny of the hundreds of smart, skeptical people, I also believe that nothing is certain. I believe that the best we can hope for is highly probable. By putting them out there and stress testing them, the probabilities of their being right will increase.

We will begin by examining the following questions:

What are principles?

Why are principles important?

Where do principles come from?

Do you have principles that you live your life by?

What are they?

How well do you think they will work, and why?

That fall I went to Harvard Business School, which I was excited about because I felt that I had climbed to the top and would be with the best of the best. Despite these high expectations, the place was even better than I expected because the case study method allowed open-ended figuring things out and debating with others to get at the best answers, rather than memorizing facts. I loved the work-hard, playhard environment.

Through this time and till now I followed the same basic approach I used as a 12-year-old caddie trying to beat the market, i.e., by 1) working for what I wanted, not for what others wanted me to do; 2) coming up with the best independent opinions I could muster to move toward my goals; 3) stresstesting my opinions by having the smartest people I could find challenge them so I could find out where I was wrong; 4) being wary about overconfidence, and good at not knowing; and 5) wrestling with reality, experiencing the results of my decisions, and reflecting on what I did to produce them so that I could improve.

Most importantly: I learned that failure is by and large due to not accepting and successfully dealing with the realities of life, and that achieving success is simply a matter of accepting and successfully dealing with all my realities. I learned that finding out what is true, regardless of what that is, including all the stuff most people think is bad—like mistakes and personal weaknesses—is good because I can then deal with these things so that they don’t stand in my way.

I learned that there is nothing to fear from truth. While some truths can be scary—for example, finding out that you have a deadly disease—knowing them allows us to deal with them better. Being truthful, and letting others be completely truthful, allows me and others to fully explore our thoughts and exposes us to the feedback that is essential for our learning.

I learned that being truthful was an extension of my freedom to be me. I believe that people who are one way on the inside and believe that they need to be another way outside to please others become conflicted and often lose touch with what they really think and feel. It’s difficult for them to be happy and almost impossible for them to be at their best. I know that’s true for me.

I learned that I want the people I deal with to say what they really believe and to listen to what others say in reply, in order to find out what is true.

I learned that one of the greatest sources of problems in our society arises from people having loads of wrong theories in their heads—often theories that are critical of others—that they won’t test by speaking to the relevant people about them. Instead, they talk behind people’s backs, which leads to pervasive misinformation.

I learned to hate this because I could see that making judgments about people so that they are tried and sentenced in your head, without asking them for their perspective, is both unethical and unproductive. So I learned to love real integrity (saying the same things as one believes) and to despise the lack of it.

I learned that everyone makes mistakes and has weaknesses and that one of the most important things that differentiates people is their approach to handling them. I learned that there is an incredible beauty to mistakes, because embedded in each mistake is a puzzle, and a gem that I could get if I solved it, i.e., a principle that I could use to reduce my mistakes in the future. I learned that each mistake was probably a reflection of something that I was (or others were) doing wrong, so if I could figure out what that was, I could learn how to be more effective.

I learned that wrestling with my problems, mistakes, and weaknesses was the training that strengthened me. Also, I learned that it was the pain of this wrestling that made me and those around me appreciate our successes.

12 I learned that the popular picture of success—which is like a glossy photo of an ideal man or woman out of a Ralph Lauren catalog, with a bio attached listing all of their accomplishments like going to the best prep schools and an Ivy League college, and getting all the answers right on tests—is an inaccurate picture of the typical successful person. I met a number of great people and learned that none of them were born great—they all made lots of mistakes and had lots weaknesses—and that great people become great by looking at their mistakes and weaknesses and figuring out how to get around them. So I learned that the people who make the most of the process of encountering reality, especially the painful obstacles, learn the most and get what they want faster than people who do not. I learned that they are the great ones—the ones I wanted to have around me. In short, I learned that being totally truthful, especially about mistakes and weaknesses, led to a rapid rate of improvement and movement toward what I wanted.

I found it more opposite than similar to most others’ approaches, which has produced communications challenges. Specifically, I found that: While most others seem to believe that learning what we are taught is the path to success, I believe that figuring out for yourself what you want and how to get it is a better path.

13 While most others seem to believe that having answers is better than having questions, I believe that having questions is better than having answers because it leads to more learning.

14 While most others seem to believe that pain is bad, I believe that pain is required to become stronger. While most others seem to believe that mistakes are bad things, I believe mistakes are good things because I believe that most learning comes via making mistakes and reflecting on them. While most others seem to believe that finding out about one’s weaknesses is a bad thing, I believe that it is a good thing because it is the first step toward finding out what to do about them and not letting them stand in your way.

15 Yes, I started Bridgewater from scratch, and now it’s a uniquely successful company and I am on the Forbes 400 list. But these results were never my goals—they were just residual outcomes—so my getting them can’t be indications of my success. And, quite frankly, I never found them very rewarding.

This brings me to my most fundamental principle: Truth —more precisely, an accurate understanding of reality— is the essential foundation for producing good outcomes.

For example, when a pack of hyenas takes down a young wildebeest, is this good or bad? At face value, this seems terrible; the poor wildebeest suffers and dies. Some people might even say that the hyenas are evil. Yet this type of apparently evil behavior exists throughout nature through all species and was created by nature, which is much smarter than I am, so before I jump to pronouncing it evil, I need to try to see if it might be good. When I think about it, like death itself, this behavior is integral to the enormously complex and efficient system that has worked for as long as there has been life. And when I think of the second- and third-order consequences, it becomes obvious that this behavior is good for both the hyenas, who are operating in their self-interest, and in the interests of the greater system, which includes the wildebeest, because killing and eating the wildebeest fosters evolution, i.e., the natural process of improvement. In fact, if I changed anything about the way that dynamic works, the overall outcome would be worse. I believe that evolution, which is the natural movement toward better adaptation, is the greatest single force in the universe, and that it is good.

18 I believe that the desire to evolve, i.e., to get better, is probably humanity’s most pervasive driving force. Enjoying your job, a craft, or your favorite sport comes from the innate satisfaction of getting better. Though most people typically think that they are striving to get things (e.g., toys, better houses, money, status, etc.) that will make them happy, that is not usually the case. Instead, when we get the things we are striving for, we rarely remain satisfied. It affects the changes of everything from all species to the entire solar system. It is good because evolution is the process of adaptation that leads to improvement. So, based on how I observe both nature and humanity working, I believe that what is bad and most punished are those things that don’t work because they are at odds with the laws of the universe and they impede evolution.

19 It is natural that it should be this way—i.e., that our lives are not satisfied by obtaining our goals rather than by striving for them—because of the law of diminishing returns. It is natural for us to seek other things or to seek to make the things we have better. In the process of this seeking, we continue to evolve and we contribute to the evolution of all that we have contact with. The things we are striving for are just the bait to get us to chase after them in order to make us evolve, and it is the evolution and not the reward itself that matters to us and those around us.

20 I believe that pursuing self-interest in harmony with the laws of the universe and contributing to evolution is universally rewarded, and what I call “good.” Look at all species in action: they are constantly pursuing their own interests and helping evolution in a symbiotic way, with most of them not even knowing that their self-serving behaviors are contributing to evolution. Like the hyenas attacking the wildebeest, successful people might not even know if or how their pursuit of self-interest helps evolution, but it typically does. For example, suppose making a lot of money is your goal and suppose you make enough so that making more has no marginal utility. Then it would be foolish to continue to have making money be your goal. People who acquire things beyond their usefulness not only will derive little or no marginal gains from these acquisitions, but they also will experience negative consequences, as with any form of gluttony. So, because of the law of diminishing returns, it is only natural that seeking something new, or seeking new depths of something old, is required to bring us satisfaction. In other words, the sequence of 1) seeking new things (goals); 2) working and learning in the process of pursuing these goals; 3) obtaining these goals; and 4) then doing this over and over again is the personal evolutionary process that fulfills most of us and moves society forward.

The Personal Evolutionary Process

As I mentioned before, I believe that life consists of an enormous number of choices that come at us and that each decision we make has consequences, so the quality of our lives depends on the quality of the decisions we make. We aren’t born with the ability to make good decisions; we learn it.

26 I believe that the way we make our dreams into reality is by constantly engaging with reality in pursuit of our dreams and by using these encounters to learn more about reality itself and how to interact with it in We all start off as children with others, typically parents, directing us. But, as we get older, we increasingly make our own choices. We choose what we are going after (i.e., our goals), which influences our directions. For example, if you want to be a doctor, you go to med school; if you want to have a family, you find a mate; and so on. As we move toward our goals, we encounter problems, make mistakes, and run into personal weaknesses. Above all else, how we choose to approach these impediments determines how fast we move toward our goals.

It is a fundamental law of nature that to evolve one has to push one’s limits, which is painful, in order to gain strength—whether it’s in the form of lifting weights, facing problems head-on, or in any other way. Nature gave us pain as a messaging device to tell us that we are approaching, or that we have exceeded, our limits in some way. At the same time, nature made the process of getting stronger require us to push our limits. Gaining strength is the adaptation process of the body and the mind to encountering one’s limits, which is painful. In other words, both pain and strength typically result from encountering one’s barriers. When we encounter pain, we are at an important juncture in our decisionmaking process. Most people react to pain badly. They have “fight or flight” reactions to it: they either strike out at whatever brought them the pain or they try to run away from it. As a result, they don’t learn to find ways around their barriers, so they encounter them over and over again and make little or no progress toward what they want.

29 Those who react well to pain that stands in the way of getting to their goals—those who understand what is causing it and how to deal with it so that it can be disposed of as a barrier—gain strength and satisfaction. This is because most learning comes from making mistakes, reflecting on the causes of the mistakes, and learning what to do differently in the future. Believe it or not, you are lucky to feel the pain if you approach it correctly, because it will signal that you need to find solutions and to progress. Since the only way you are going to find solutions to painful problems is by thinking deeply about them—i.e., reflecting

30—if you can develop a knee-jerk reaction to pain that is to reflect rather than to fight or flee, it will lead to your rapid learning/evolving.

31 In other words, “The Process” consists of five distinct steps: Have clear goals. Identify and don’t tolerate the problems that stand in the way of achieving your goals. Accurately diagnose

40 The you I am referring to here is the strategic you – the one who is deciding on what you want and how best to get it, previously referred to as you.

Design plans that explicitly lay out tasks that will get you around your problems and on to your goals. Implement these plans—i.e., do 1) You must approach these as distinct steps rather than blur them together. For example, when setting goals, just set goals (don’t think how you will achieve them or the other steps); when diagnosing problems, just diagnose problems (don’t think about how you will solve them or the other steps). Blurring the steps leads to suboptimal outcomes because it creates confusion and short-changes the individual steps. Doing each step thoroughly will provide information that will help you do the other steps well, since the process is iterative. these tasks.

2) Each of these five steps requires different talents and disciplines. Most probably, you have lots of some of these and inadequate amounts of others. If you are missing any of the required talents and disciplines, that is not an insurmountable problem because you can acquire them, supplement them, or compensate for not having them, if you recognize your weaknesses and design around them. So you must be honestly self-reflective. 3) It is essential to approach this process in a very clear-headed, rational way rather than emotionally. Figure out what techniques work best for you; e.g., if emotions are getting the better of you, take time out until you can reflect unemotionally, seek the guidance of calm, thoughtful others, etc.