The ESSENTIAL and ULTIMATE guide to English Language Teaching

Scott Thornbury- number one! (and Adrian Underhill)

with further reading and links at the bottom

Logos, pathos and ethos… who has them in the field of English Language teaching? Obviously, Scott, but if you haven’t heard of him already, what could i possibly say (with no ethos) that would make you read him?

So I’ll just rely on logos and the man himself and the many English Language professionals who interact with him.

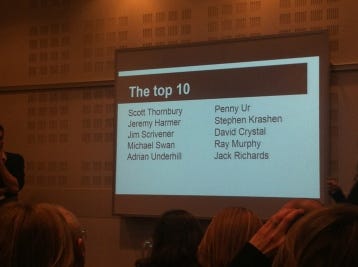

In this excellent talk, Nicola Prentis and Russell Mayne ask where all the women are in English Language Teaching. As part of the talk, they received over 500 responses to the question “Who would you say are the ‘big names’ in ELT”, and Scott Thornbury is number 1.

https://genderequalityelt.wordpress.com/where-are-the-women-in-elt-iatefl-talk/

Here is his article on Grammar McNuggets, perhaps his most important idea.

“Much of what is taught as pedagogic grammar is of equally doubtful authenticity. The skin, gristle and bones of language have been removed such that “grammar exists independently of other aspects of language such as vocabulary and phonology” (Kerr, 1996: 95). Moreover, the findings of corpus linguistics in particular suggest that pedagogic grammars only loosely reflect authentic language use and that “some relatively common linguistic constructions are overlooked, while some relatively rare constructions receive considerable attention” (Biber, et al. 1994, p. 171).

https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2010/09/18/g-is-for-grammar-mcnuggets/

If you’re still teaching McNugget style, surely you could at least give this a chance?

https://learnjam.com/who-ordered-the-mcnuggets/

If I had to reduce language learning to the bare essentials and then construct a methodology around those essentials, it might look something like this (from Edmund White’s autobiographical novel The Farewell Symphony):

[Lucrezia’s] teaching method was clever. She invited me to gossip away in Italian as best I could, discussing what I would ordinarily discuss in English; when stumped for the next expression, I’d pause. She’d then provide the missing word. I’d write it down in a notebook I kept week after week. … Day after day I trekked to Lucrezia’s and she tore out the seams of my shoddy, ill-fitting Italian and found ways to tailor it to my needs and interests.

https://learnjam.com/intersubjectivity-is-there-an-app-for-that/

***

part 2

extract from Scott

“Let’s start with the syllabus. I surveyed five intermediate coursebook syllabuses, ranging from 1996 to 2009, and found the following items were common to all five, more or less in the same order:

present simple and continuous

past simple and continuous

future forms (going to, will)

present perfect vs past simple

present perfect continuous

modal verbs of deduction/probability

first conditional

second conditional

reported speech

passive

Why is this? On what grounds have these items been selected and ordered in this way? Frequency? Complexity? Usefulness? Learnability? Or simply convention? Either way, this ‘canonical’ syllabus is endlessly reproduced with only minor variations, as are the syllabuses for all other levels in the curriculum. They can hardly be considered original.

Associated with the syllabus is the way a number of grammar myths are propagated from course to course, like mutant genes. Principal among these is the conflating of tense and aspect, and defining both in terms of time, as in ‘the Present Continuous is used to express an activity happening now’ (coursebook published in 1991) and ‘we use the Present Continuous to talk about things happening now’ (coursebook published in 2010). The article system and the use of passive voice are also prime candidates for this kind of accidental cross-fertilization. It’s as if the only grammars that these writers consulted are each other’s.

What about topics? Well, you only have to flip through a selection of adult courses and note the way that the same, relatively limited set of topics resurface again and again: friends and family, home and neighbourhood, leisure activities, travel, shopping and clothes, health and nutrition, technology and the future, popular culture and entertainment, the environment…. Arguably, these are chosen because of the coverage they offer with regard to learners’ lexical needs, as well as the kinds of situations which learners might find themselves in. But this is largely guesswork.

Another reason, of course, why the topical content is fairly repetitive (and pervasively upbeat) is that there are many topics (like sex, religion, and politics) which, through fear of causing offence or discomfort, cannot be mentioned. Since sex, religion and politics tend to impact in significant ways on people’s lives – and hence on their use of language – this is a severe limitation.

discussion/replies

I think that the McNugget approach in parts creates the illusion of learning and progress for students and teachers. And that in turn creates motivation. And motivation, as we know, is the key to language teaching. I’m not trying to pull a 3-card monte, I’m serious. I recognise the dangers of commodification and I have no interest in defending it (only in spelling it correctly), but having taught/trained/lived in an EFL context for 25+ years, and having observed the full range of successes and failures in the language learning process, I think there are factors at work that research and theory will always struggle to pinpoint. As a teacher (and learner) strongly biased against tidy packaging of grammar, I’ve resisted acknowledging what I see evidence for all too frequently, that for certain learners, the sensation of learning actually leads somehow to… learning.

****

I also agree with Steve as well as Scott- it makes me think of the Henry ford quote- “Whether you think you can, or whether you think you can't--you're probably right.”

***

back to Scott

“Perhaps it is that discourse that is part of the broader problem?”

Agreed, Philip. You mentioned earlier that there are at least two positions available, with regard to effecting change: ‘ Those who nibble away at the edges … , or those who, Canute-like, refuse to understand how tides work’. There is a third, I would venture, which is the caged canary in the coalmine, warbling warningly at the smell of encroaching gas. Gas- (or crap-) detectors don’t often have a direct effect on change, but for them it’s enough if the stakeholders start asking questions: Is that really gas? Are coursebooks really original?

For all its excesses, I think that the Dogme group has done a good job at alerting the profession to the rising levels of crap, not least about the slavish devotion to materials and technology (although it may have generated some crap of its own).

I used the canary in the coalmine metaphor in a talk today, and was informed that, of course, the canary doesn’t warble its warning, it simply drops dead. So, maybe it’s not the best analogy!

Alex Case I find primary courses to be the most similar of all, hence my own rant on the topic:

http://tefltastic.wordpress.com/2013/07/08/super-minds/

(The ranty bit in there was edited out when the review appeared in Modern English Teacher magazine).

I find ESP and Biz texbooks to be more innovative, if also only within certain limits. However, they are also a good example of one reason why “innovative” courses are not as popular as perhaps once they were – a lot of them turned out to be pants, probably because the concept became all. See for some of the many examples of this English Panorama, Innovations, Working Week, Natural English, Cutting Edge first edition, ….

all from here

https://learnjam.com/writing-by-numbers-the-myth-of-coursebook-creativity/

*****

http://www.scottthornbury.com/articles.html

Here is his site

https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/

Here’s an interview with Nicola and Russell before they gave their talk: https://iatefl.britishcouncil.org/2015/interview/interview-nicola-prentis-and-russel-mayne

how to teach without nuggets

https://cerij.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/following-a-thread/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/q-scott-thornbury-daniel-israel/

**

in order to draw up a useable set of criteria for gauging the learning power of any new edtech tool, I’m going to borrow from a selection of ‘state of the art’ papers on SLA (see bibliography below). Following VanPatten and Williams (2007), for example, I’m going to draw up a list of ‘observations’ about SLA that have been culled from the research. On the basis of these, and inspired by Long (2011), I will then attempt to frame some questions that can be asked of any educational technology in order to predict its potential for facilitating learning.

Here, then, are the 10 observations:

1. The acquisition of an L2 grammar follows a ‘natural order’ that is roughly the same for all learners, independent of age, L1, instructional approach, etc., although there is considerable variability in terms of the rate of acquisition and of ultimate achievement (Ellis 2008), and, moreover, ‘a good deal of SLA happens incidentally’ (VanPatten and Williams 2007).

2. ‘The learner’s task is enormous because language is enormously complex’ (Lightbown 2000).

3. ‘Exposure to input is necessary’ (VanPatten and Williams 2007).

4. ‘Language learners can benefit from noticing salient features of the input’ (Tomlinson 2011).

5. Learners benefit when their linguistic resources are stretched to meet their communicative needs (Swain 1995).

6. ‘There is clear evidence that corrective feedback contributes to learning’ (Ellis 2008).

7. Learners can learn from each other during communicative interaction (Swain et al. 2003).

8. Fluency is an effect of having a large store of memorized sequences or chunks (Nattinger & DeCarrico 1992; Segalowitz 2010).

9. Learning, particularly of words, is aided when the learner makes strong associations with the new material (Sökmen 1997).

10. All things being equal, the more time (and the more intensive the time) spent learning and using the language, the better (Muñoz 2012).

On the basis of these observations, the following questions can be formulated:

1. ADAPTIVITY: Does the software assume that learning is linear, incremental, uniform, predictable and intentional? Or does it accommodate the often recursive, stochastic, incidental, and idiosyncratic nature of learning, e.g. by revisiting material, by adapting to the user’s learning history, by allowing the users to set their own learning paths and goals?

2. COMPLEXITY: Does the software address the complexity of language, including its multiple interrelated sub-systems (e.g. grammar, lexis, phonology, discourse, pragmatics)?

3. INPUT: Is material provided for reading and/or listening, and is this input rich, comprehensible, and engaging? Are there means by which the input can be made more comprehensible? And is there a lot of input (so as to optimize the chances of repeated encounters with language items, and of incidental learning)?

4. FOCUS ON FORM: Are there mechanisms whereby the user’s attention is directed to features of the input and/or mechanisms that the user can enlist to make features of the input salient?

5. OUTPUT: Are there opportunities for language production? Are there means whereby the user is pushed to produce language at or even beyond his/her current level of competence?

6. FEEDBACK: Does the user get focused feedback on their comprehension and production, including feedback on error?

7. INTERACTION: Is there provision for the user to collaborate and interact with other users (whether other learners or proficient speakers) in the target language?

8. CHUNKS: Does the software encourage/facilitate the acquisition and use of formulaic language?

9. PERSONALIZATION: Does the software encourage the user to form strong personal associations with the material?

10. INVESTMENT: Is the software sufficiently engaging/motivating to increase the likelihood of sustained and repeated use?

some responses here

https://learnjam.com/how-could-sla-research-inform-edtech/

https://www.englishcentral.com/browse/videos?setLanguage=en

I’m missing some input to this from the area of cognitive neuroscience, and in particular research into how memory works: the transfer of language items from working memory to long-term memory, and then recall back the other way into working memory for active production.

There are many good articles on this from an eLearning perspective, and this one is as good a place to start as any:

http://info.shiftelearning.com/neuroscience-based-elearning-tips/

Here is a paste from the Table Of Contents of this article:

Tip 1: Important stuff comes first

Tip 2: Encourage consistent practice

Tip 3: Introduce novelty

Tip 4: Create multi-sensory learning experiences

Tip 5: Favor recognition over recall

Tip 6: Break your content into bite-sized chunks

Tip 7: Help learners access previous knowledge

Tip 8: Try more contrast

Tip 9: Enhance the relevancy of learning

Tip 10: The spacing effect

Tip 11: Trigger the right emotion

Tip 12: Balance emotion and cognition

Some of this is clearly mirrored in Scott’s article, eg Tip 6 and 7. But other ‘Tips’ seem important and missing from Scott’s observations. In particular, Tip 10 – the importance of ‘spaced repetition’. Neuroscience research argues that the space between the times when a student recycles and revises is absolutely critical. It’s in that space that neurones physically grow in the brain and synapses physically connect. Each revision event gives a further turn round memory and a further strengthening of the synapses.

Ebbinghaus wrote about this in 1885: his ‘forgetting curve’ is of central importance to learning of any kind.

I have always told my students: ‘Look at your notes and coursebook texts again tonight, then again in a few days time, then again in a week, then again in a month. That’s the best possible way to learn’. And I remind/encourage them. That’s how I learned how to play the bass guitar, how to drive, how to cook my repertoire of dishes, and how to do yoga poses. Spaced repetition. It’s how we all learn everything.

So here’s the question for SLA and eLearning: what makes for the best kind of revision? Just re-reading the input and re-doing the exercises? Or looking at the vocabulary or grammar or functional phrases again but in a different context?

eLearning makes ‘doing it again’ very easy. But most eLearning that I have seen doesn’t encourage this. You get the big green tick and ‘Completed’ on the LMS and move on. Any suggestion that this material might be forgotten and needs revisiting is absent.

https://learnjam.com/how-could-sla-research-inform-edtech/

**

more Scott

Scott Thornbury's 101 Grammar Questions

Download a free sample: https://camengli.sh/2k7St6m

Learn more about the book: https://camengli.sh/2lKuXN6

some criticism

wordle?

https://kenwilsonelt.wordpress.com/2009/11/22/putting-it-all-into-perspective/

Let’s look at the other top 5, starting with Adrian Underhill, the guru of pronunciation

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLbEWGLATRxw_2hL5hY164nvHdTpwhEOXC

“We are aiming at comfortable intelligibility.” Adrian Underhill

https://adrianpronchart.wordpress.com/about-this-site/

https://adrianpronchart.wordpress.com/2015/11/30/comfortable-intelligibility-2/

Scott

https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/t-is-for-teacher-knowledge/

more Scott

https://x.com/michaelegriffin/status/1668580217538113536

Michael Griffin and Russ Mayne

https://eltrantsreviewsreflections.wordpress.com/2014/04/04/interview-with-ebefl/

Steve Brown

https://stevebrown70.wordpress.com/2014/04/05/never-mind-the-boocks-heres-the-tefl-skeptic/

https://stevebrown70.wordpress.com/2015/02/01/jordan-scriverhill-and-guru-bashing/

https://simpleenglishuk.wordpress.com/2014/04/06/a-glut-of-elt-celebrity-encounters/

Hugh Dellar