[COPY] Jan 2025 Sciences Po English course part 2

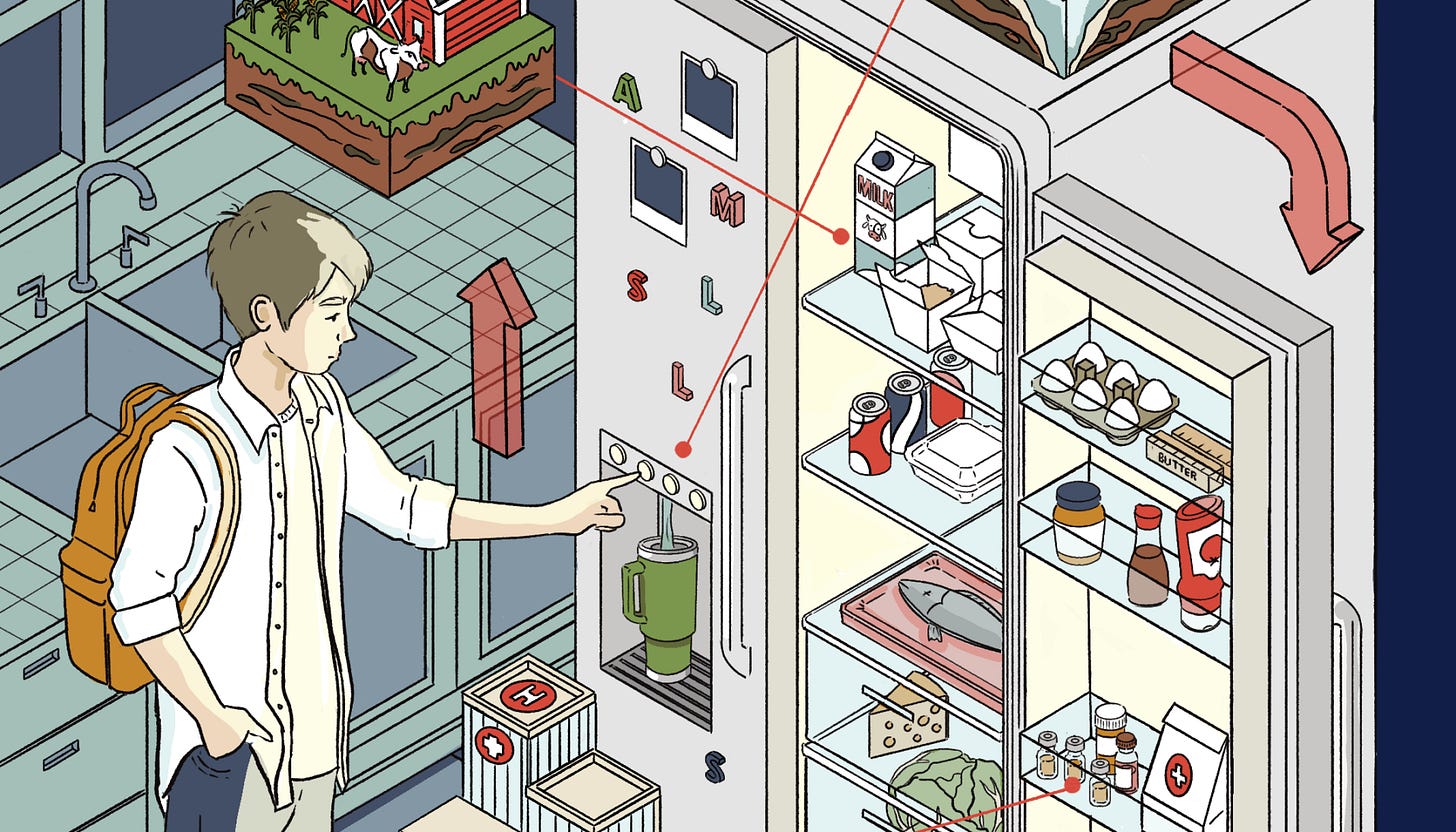

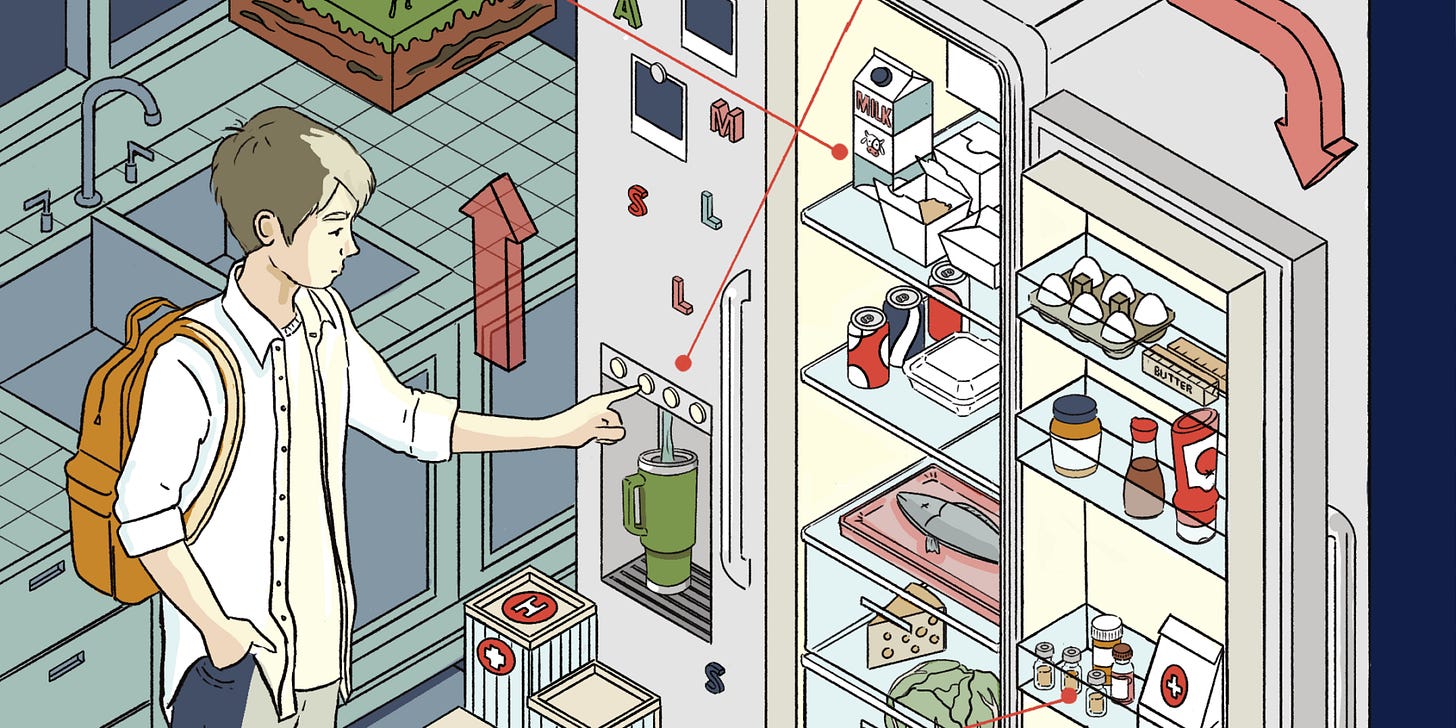

Living together https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/mar/08/the-only-way-i-can-survive-co-living-as-a-single-parent

a/an European policy?

Verbs followed by infinitive/gerund

causative verbs

https://englishwithjennifer.wordpress.com/2010/10/18/student-stumper-24-causative-verbs/

Fuchs and Bonner

a list of 32 verbs from Fuchs and Bonner:

advise, allow, ask, cause, challenge, choose, convince, enable, encourage, expect, forbid, force, get, help, hire, invite, need, order, pay, permit, presuade, promise, remind, request, require, teach, tell, urge, want, warn, wish, would like

Please use control F and composition// Week 1/2/ 3/ TOEFL// Esther Duflo// Cummings kayfabe/ Romer/ Chappelle/ Wolf/ Joy/ Unabomber/ Thiel/ Orfalea/ Eliot/ Lessing/tax /Silver/ Biden/ Harris/ Bayes// Covid/ Luria// counterfactuals// Taleb/ hedgehog/ Tetlock/ Bilderberg- Thiel// Marx/ Fonda/ Frankl/ Steve Jobs/drugs/ Taibbi/ Hamming /Charles C Mann// CIA from Unherd

to find the part you need.

add your name here

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1bntndQtQbz-PSu-7azPW_8qSDT1_S9CQyMBR63-1w4E/edit?userstoinvite=stuart.wiffin%40sciencespo.fr&gid=0#gid=0

Week 12 23.4.25

Trade-offs

Hard choices for Keir Starmer- if he gets rid of this policy, will he still be PM?

As of the latest data available, there were nearly 9.1 million pupils across all school types in the UK during the academic year 2023/24.6 This figure includes children from early years through to secondary education. Additionally, the population of children in care, known as "looked after children," was approximately 107,000 in 2022/23.

child poverty here

and the concept of relative poverty below Diamandis

The Pope

“As I meet, or lend an ear to those who are sick,

to the migrants who face terrible hardships

in search of a brighter future,

to prison inmates who carry a hell of pain inside their hearts,

and to those, many of them young, who cannot find a job,

I often find myself wondering:

"Why them and not me?"

I, myself, was born in a family of migrants;

my father, my grandparents, like many other Italians,

left for Argentina

and met the fate of those who are left with nothing.

I could have very well ended up among today's "discarded" people.

And that's why I always ask myself, deep in my heart:

"Why them and not me?"

***

Happiness can only be discovered

as a gift of harmony between the whole and each single component.

Even science – and you know it better than I do –

points to an understanding of reality

as a place where every element connects and interacts with everything else.**

Mother Teresa actually said:

"One cannot love, unless it is at their own expense."

cf

Orwell on coolies and Hitchens on Mother Teresa

poverty https://www.ted.com/talks/peter_diamandis_abundance_is_our_future

Tim Harford https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_harford_trial_error_and_the_god_complex

nationalisation

from the Telegraph

The second home tax is punitive, petty and politically motivated

Joe Wright

Senior Money Writer

Tax rises are never popular, but I think we have a winner. Second home owners feel that they are being unjustly targeted and treated as cash cows. Understandably, they're not happy.

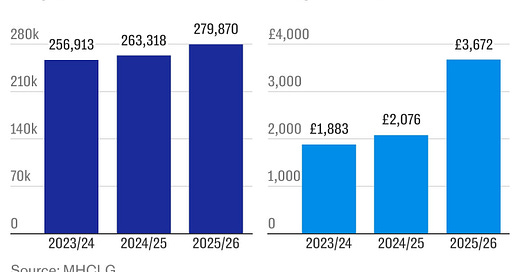

Two thirds of local authorities across England have this month brought in a double council tax charge on second homes, piling misery on 280,000 owners who will see their bills rise 77 per cent to £3,672, on average, according to analysis by The Telegraph. In some areas, council tax bills for second homes will surpass £10,000.

I’ve rarely seen a topic enrage readers like this stealth tax on wealth. The Telegraph’s inbox has been inundated with emails of woe from those who feel that they have done nothing wrong but are being financially penalised. Property owners tell us they feel more like residents in their second home area than their hometown, taking great efforts to get to know their neighbours and pumping money into the economy. Yet councils want them gone, ostensibly to free up homes in holiday hotspots for local buyers and to raise funds to tackle housing shortages.

These have already failed to hold up to scrutiny, with holiday “notspots” (really, Bradford?) also capitalising on the chance to raid wallets and councils spending just 9p of every £1 raised on affordable housing.

Worst of all? The Government has admitted it has no idea what effect this policy will have on house prices or the number of second homes. This sorry state of affairs appears to be a politically-motivated crackdown on perceived wealth – and it may well backfire.

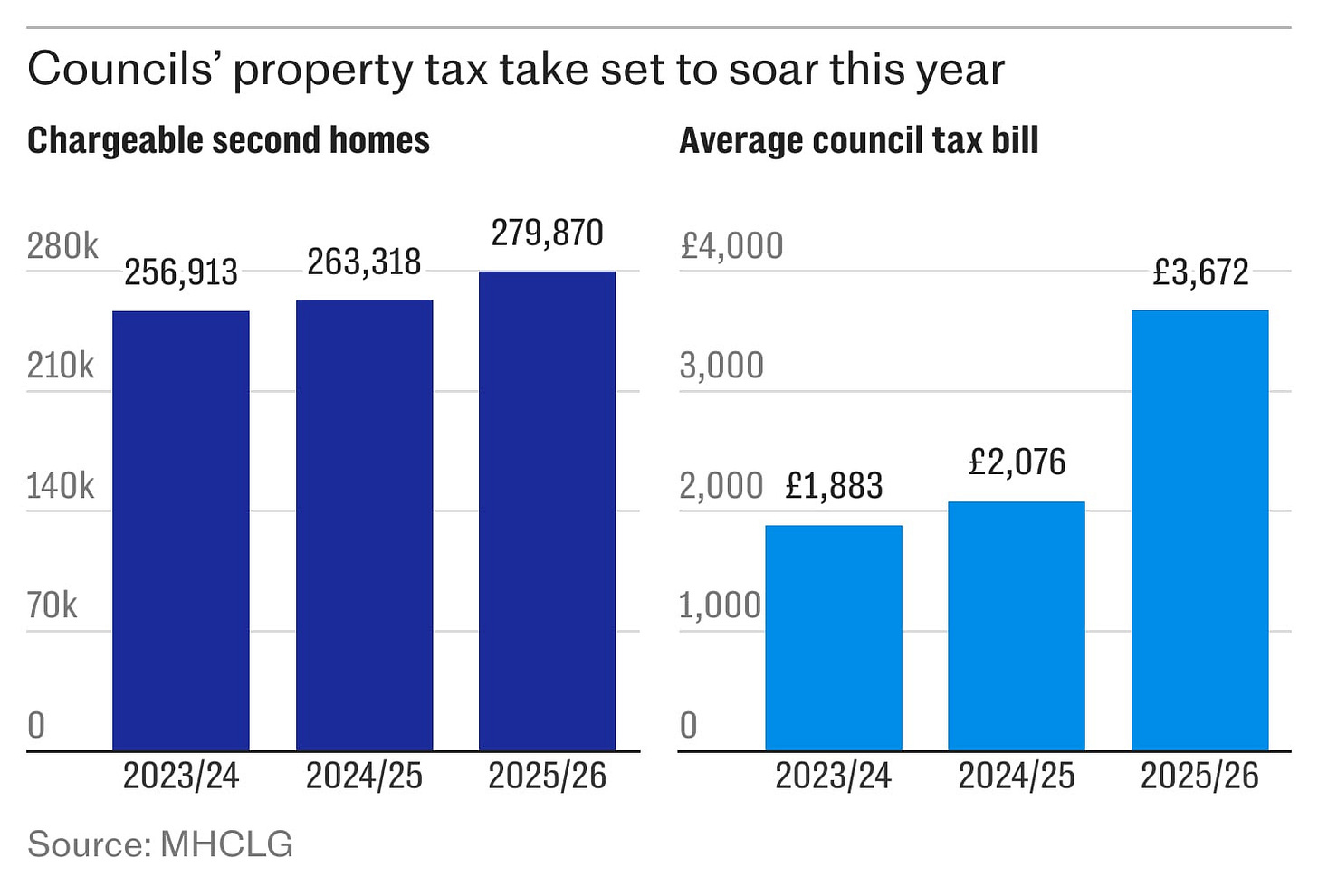

In 2013, the Government attempted a similar attack on empty homes, giving local authorities powers to increase council taxes by 50 per cent, with quadruple bills for properties unfilled for over a decade. I dug into the numbers and discovered that the situation is worse now than it was before, with the number of empty homes at a 14-year high.

Could a similar fate befall second homes? It certainly appears so. My colleague Pieter Snepvangers went to Wales, where the second home council tax surcharge was introduced a year ago, and found that the country had succumbed to a “lose-lose” situation where house prices have plunged but still remain out of the budget of local buyers.

Questions are also swirling about the legality of the crackdown. Homeowners tell us that they were “blindsided” when the tax bill landed on their doormat. They say the policy amounts to “taxation without representation” as second home owners cannot vote in local elections and are being billed twice for council services that they cannot use.

Some savvy owners are already deploying legally sound tactics to swerve the hefty bills. By listing a second home for sale (and marketing it at a reasonable price) you’ll be awarded with a 12-month exemption to the premium from your local council. It’s a neat trick and one where there is no obligation to sell.

But this should be unnecessary, as second home owners shouldn’t be penalised for inheriting a family home or investing their hard-earned money in property instead of stocks. That’s why The Telegraph is calling on the Government to abolish this punitive, petty premium. Have you been affected by double council tax on second homes?

conterfactuals Luria Black Swan Taleb

Did Paul Graham more on Y Combinator, Aaron Swartz Failure at Ycombinator link??????

Mean people fail https://www.paulgraham.com/mean.html

China US export stats

https://x.com/SpencerHakimian/status/1909059731748167963

https://avc.com/2014/10/paul-graham-dropping-serious-wisdom/

***

personality test- “I ramp up views”

https://www.theguardian.com/wellness/2025/apr/14/why-am-i-like-this-disagreeable

***

plus size models- Ozempic https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2025/apr/15/ozempic-arrived-and-everything-changed-plus-size-models-on-the-body-positivity-backlash

****

steel

On Saturday, when MPs were supposed to be on their Easter holidays, a rare emergency sitting was called. Jonathan Reynolds, the business secretary, told the House of Commons that they were meeting “in exceptional circumstances to take exceptional action in what are exceptional times”.

MPs passed a bill to save the Scunthorpe steelworks, a vital part of the UK’s critical infrastructure and the last remaining maker of mass-produced virgin steel. The emergency legislation allowed the government to instruct the Chinese owners of the British Steel plant, Jingye, to keep Scunthorpe open or face criminal penalties.

Jasper Jolly is a financial reporter for the Guardian. He tells Helen Pidd that the steelworks are central to life in Scunthorpe and that their loss would be devastating for the town. He explains that the plant has been loss-making for several years and that it is largely the glut of cheap Chinese steel in the global market that has led its owners to consider its closure.

The pair discuss why the government has taken control of Scunthorpe in a way that it did not with the Port Talbot steelworks, the race to keep the blast furnaces hot, and the way that this crisis has led many to question the wisdom of selling critical parts of the UK’s infrastructure to foreign and private companies.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2025/apr/15/the-scramble-to-save-british-steel-podcast

**

space

*****

“I am broadly of the view that Katy Perry should do whatever she likes, and wear whatever she likes, and if she wants to be shot into space for no obvious purpose looking like one of Charlie’s Angels, then that falls squarely into those categories. So why am I so bothered by Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, which has just made a suborbital flight to the edge of space and back? OK, it’s partly the outfits (see Angels, Charlie’s, above), but it’s mainly the flight manifest: Perry joined Lauren Sánchez, Jeff Bezos’s fiancee; Amanda Nguyen, a civil rights activist; CBS Mornings co-host Gayle King; film producer Kerianne Flynn and former Nasa rocket scientist Aisha Bowe. I cannot help but notice that only two of these women had anything to do with astronauting (Nguyen studied astrophysics and interned at Nasa before becoming an activist).

Obviously it’s very staid and 20th century to think that only experts should be allowed in space – yet their absence did suggest the primary purpose of the trip to be tourism rather than research. Which in turn suggests that this was a dumb waste of money. Which itself makes you wonder just how many of the world’s problems would have to have been solved before space tourism would look like a worthwhile enterprise – hard to put a number on it, but significantly more than have been solved today.”

from CNN

Karman line 62 miles above sea level

week 11

aaron the logic of the situation

Ozempic price? https://www.doktorabc.com/fr/ordonnance/ozempic/ozempic-prix

no easy answers, trade-offs?

997 a month- who pays?

https://ro.co/weight-loss/ozempic-cost-without-insurance/

cancer drug

The cost of cancer drugs has been a significant concern, with some drugs priced at over $100,000 per patient for one year of treatment, and more recently, launch prices exceeding $400,000 for a year of treatment.32 For instance, ipilimumab (Yervoy), approved for treating metastatic melanoma, costs $120,000 for four doses.1 Global spending on cancer drugs reached a record $185 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach $307 billion by 2030.2 Despite the high costs, there is no evidence that the savings from developing precision oncology drugs, which could be $1 billion cheaper to develop than non-precision drugs, will lead to more affordable cancer medicines.

Orwell.International socialism.

“In England there is only one Socialist party that has ever seriously mattered, the Labour Party. It has never been able to achieve any major change, because except in purely domestic matters it has never possessed a genuinely independent policy. It was and is primarily a party of the trade unions, devoted to raising wages and improving working conditions. This meant that all through the critical years it was directly interested in the prosperity of British capitalism. In particular it was interested in the maintenance of the British Empire, for the wealth of England was drawn largely from Asia and Africa. The standard of living of the trade-union workers, whom the Labour Party represented, depended indirectly on the sweating of Indian coolies. At the same time the Labour Party was a Socialist party, using Socialist phraseology, thinking in terms of an old-fashioned anti-imperialism and more or less pledged to make restitution to the coloured races. It had to stand for the ‘independence’ of India, just as it had to stand for disarmament and ‘progress’ generally. Nevertheless everyone was aware that this was nonsense. In the age of the tank and the bombing plane, backward agricultural countries like India and the African colonies can no more be independent than can a cat or a dog. Had any Labour government come into office with a clear majority and then proceeded to grant India anything that could truly be called independence, India would simply have been absorbed by Japan, or divided between Japan and Russia.”

“A Socialist Party which genuinely wished to achieve anything would have started by facing several facts which to this day are considered unmentionable in left-wing circles. It would have recognized that England is more united than most countries, that the British workers have a great deal to lose besides their chains, and that the differences in outlook and habits between class and class are rapidly diminishing. In general, it would have recognized that the old-fashioned ‘proletarian revolution’ is an impossibility.”

nationalize steel and coal??????

https://x.com/trevgoes4th/status/1911366527867068714

****

Sandel- killling in the army sgt B

16.4 deadline for 3rd composition

either https://www.toeflresources.com/toefl-discussion-board-writing-question-city-spending/

or

https://www.toeflresources.com/toefl-academic-discussion-writing-question-price-controls/

or

How should France deal with the problem of homelessness?

or

Does France need an independent nuclear defence?

or

France should have a universal basic income.Discuss.

or

We should require people of all genders to register for the draft.

week 10 9.4

L'Institut des Compétences et de l'Innovation a le plaisir de nous inviter à l'évènement "Comprendre nos étudiants : attentes et attitudes de la génération Z" qui aura lieu ce jeudi 10 avril, 10h30-12h au Learning Lab (1 place Saint-Thomas) et sur Zoom. Ce lien https://www.billetweb.fr/ici-evenements-du-learning-lab-2024-2025 permet de s'y inscrire. Vous y trouverez également une brève description.

Vous souhaitant une agréable journée et bien cordialement,

Homelessness from Scott

Engage in good faith- “you’re all wrong”

‘the logic of the situation’

Andrew Chambers

Senghor

“And one of the things that we talked about is the three things that I found important in my personal transformation, the first being acknowledgment. I had to acknowledge that I had hurt others.I also had to acknowledge that I had been hurt.The second thing was apologizing. I had to apologize to the people I had hurt.Even though I had no expectations of them accepting it,it was important to do because it was the right thing. But I also had to apologize to myself. The third thing was atoning. For me, atoning meant going back into my community and working with at-risk youthwho were on the same path, but also becoming at one with myself.”

“So what I'm asking today is that you envision a world where men and women aren't held hostage to their pasts, where misdeeds and mistakes don't define you for the rest of your life.”

Ray Dalio

hedgers

from linked in

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/effects-tariffs-how-machine-works-ray-dalio-vg96e/

“Additionally, there is a lot of talk now about whether it is a helpful or harmful thing that 1) the the U.S. dollar is the world’s primary reserve currency and 2) the dollar is strong. It is clearly a good thing that the dollar is a reserve currency (because it creates a greater demand for its debt and other capital than would otherwise exist if the U.S. doesn’t have that privilege to abuse via over-borrowing). Though since the markets drive such things, it inevitably contributes to abusing this privilege and over-borrowing and debt problems which has gotten us to where we now are (i.e., needing to deal with the inevitable reducing of goods, services, and capital imbalances, needing to take extraordinary measures to reduce the debt burdens, and reducing foreign dependencies on these things because of geopolitical circumstances.) More specifically, it has been said that China’s RMB should be appreciated which probably could be agreed to between the Americans and Chinese as part of some trade and capital deal, ideally made when Trump and Xi meet. That and/or other non-market, non-economic adjustments would have unique and challenging impacts on the countries they apply to, which would lead to some of the second order consequences I mentioned earlier happening to cushion the effects.”

dalio tedtalk

currency trading

The renminbi (Chinese: 人民币; pinyin: Rénmínbì; lit. 'People's Currency' Chinese pronunciation: [ʐən˧˥min˧˥pi˥˩]; symbol: ¥; ISO code: CNY; abbreviation: RMB), also known as the Chinese yuan, is the official currency of the People's Republic of China.[a] The renminbi is issued by the People's Bank of China, the monetary authority of China.[3] It is the world's fifth-most-traded currency as of April 2022.[4]

What % of currency trading is speculation?

Galloway tedtalk

Scott Galloway https://www.profgalloway.com/earners-vs-owners-2/

Orwell on Gandhi https://stuartwiffin.substack.com/p/orwell-on-gandhi?utm_source=publication-search

Week 9 2.4

Harari chain of events

“There is no such thing as a chain of events” see Taleb below

Yuval Noah Harari

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Taleb

Charlie Rose

T

https://x.com/rohanpaul_ai/status/1883601254318039148

To

from the New Yorker

On a blanket on the lawn under a cedrillatoona tree, in Southern Rhodesia, in 1942, a young woman sat explaining to her two children why she was leaving them. The boy was three years old and the girl not yet two, but she believed that they would understand someday, and thank her. She was going off to forge a better world than the one she herself had grown up in, a world without race hatred or injustice, a world full of marvellous people. She later admitted that she really hadn’t been much interested in politics; what had drawn her to the local Communist Party was the love of literature that she’d found she shared with its members—some twenty mostly well-off, young white people who formed a self-designated Party branch in nearby Salisbury—and the sense of heroic expectation that surrounded their lives. They were eagerly awaiting the revolution that they believed would end the hateful white regime, and, if their activities were principally confined to meetings and disputes and love affairs with one another, their goals were undeniably noble. The newest comrade had not yet begun to consider the disparity between their professed goals and their actions, possibly because she could not afford to consider the disparity between her own.

Doris Lessing’s stingingly self-mocking account of her escape from maternal to global responsibility appeared just a few years ago, in the first volume of her autobiography, “Under My Skin.” Now the second volume, “Walking in the Shade” (HarperCollins; $27.50), carries her story up to its political and emotional climax, twenty years later, with the publication of her most celebrated novel, “The Golden Notebook”—which has been in print since 1962 and become a fixture of the social history it helped to shape. Many of the scenes in these memoirs are already familiar, since Lessing has drawn on the particulars of her experience throughout the broad reaches of her fiction, characteristically joining the daily realities of life on the veldt or in a London flat to the biggest political issues of the age.

“After all, you aren’t someone who writes little novels about the emotions. You write about what’s real,” a Party comrade assures “The Golden Notebook” ’s emphatically autobiographical heroine, Anna Wulf. A fully self-conscious specimen of the “position of women in our time,” Anna is also an individual of high neurotic distinction, the very model of the modern madwoman who has found her way down from the attic to the bedroom only to stand fumbling for decades with the next set of keys. It is Anna—an earnest revolutionary with a weakness for scarred and brooding men—who patiently writes and assembles the many parts of “The Golden Notebook” itself: an old-fashioned baggy monster of a modern novel, at once didactic and feverishly intense, thick with sermons and stories about African racial policy and Soviet Communism and the modern male’s inability to love and the vaginal orgasm and the question of whether women can ever be free. Anna’s goal is to write a book that will change the way people see the world, and many readers of “The Golden Notebook” claim that Lessing herself accomplished something remarkably like that.

Get The New Yorker’s daily newsletter

Keep up with everything we offer, plus exclusives available only to newsletter readers, directly in your in-box.

Sign up

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

“Walking in the Shade,” which begins with Lessing’s arrival in England, in 1949, just after the end of her second marriage, takes a far more caustic view of these goals and possible accomplishments. A blunt and hasty book, it provides a less compelling—even a less convincing—version of Lessing’s life than the complex novel whose themes it shares. Yet the memoir is a valuable guide to the equally complex human being who now questions whether that novel was worth writing, and a portrait of the artist as a woman and a thinker which is as troubling as it was evidently meant to be.

“Iwas free. I could at last be wholly myself” the gay divorcée exulted as she caught sight of London from the ship she’d boarded in Cape Town. “A clean slate, a new page—everything still to come.” Readers’ expectations of a triumphant resolution to “A Doll’s House,” however, are quickly smashed. Looking back, Lessing is sardonic, even accusing, as she marvels at what she terms her adolescent sense of self-possession. In the modern self-experiment of a life she had begun, freedom would turn out to be much harder to use than it was to win.

She was nearly thirty; and had brought with her the manuscript of her first novel and also a son, aged two and a half. Her second marriage had been no more than a wartime arrangement made to avail a German lover in Rhodesia of her British citizenship. To her surprise, she’d found that she yearned for another baby—a yearning that she now accuses Mother Nature of having aroused in order to make up for the war’s wounded and dead. Against such a force she hadn’t a choice. And so her account of her early London days becomes a catalogue of the hardships of single motherhood, what with getting up at five, working for too little money, feeling ever duty-bound and exhausted. Then, there was the tremendous loneliness and exclusion from adult society. London was still a dark and blinkered city, a barely recovered war casualty itself. She describes walking the empty streets alone at night, and the tantalizing glimpses of fellowship in the lighted pubs she sometimes passed. And one feels that if only these pubs had been a little less beery or more welcoming to a foreign woman Lessing might not have committed “probably the most neurotic act of my life,” about a year after her arrival, by officially joining the Communist Party. She writes:

I did know it was a neurotic decision, for it was characterised by that dragging helpless feeling, as if I had been drugged or hypnotised—like getting married the first time because the war drums were beating, or having babies when I had decided not to—pulled by the nose like a fish on a line.

If this lends some limited clarity to her reasons for joining, a good deal of the book is spent anxiously trying to explain why she stayed on past so many protests of her conscience. Riddled by doubts from the start, she was increasingly dismayed by the petty corruption of the British Communist bureaucracy and by evidence of the deadly Soviet variety, impossible for even the most faithful to ignore after Khrushchev’s 1956 revelations of Stalin’s atrocities and the military suppression of Hungary later that year. In fact, she was sufficiently outraged about Hungary to write a “passionate letter protesting about it” to—astonishingly—the Union of Soviet Writers. Perhaps no one has taken the power of the pen more literally; one longs to have witnessed the bleakly Gogolian farce out of which a “conciliatory letter” was produced for her edification and sent by return post. And still she struggled with turning in her Party card. In her memoirs Lessing often blames the undertow of history itself: if her feelings were neurotic, her thinking belonged to the “Zeitgeist.” What she was always secretly hoping for, she writes, was the emergence of a few pure Russian souls to put the system back on its true path.

The most perplexing and dispiriting of her adventures, however, occurred when she came upon just such a soul, and the message was not what she wanted to hear. In 1952, while she was visiting the Soviet Union and touring a collective farm, a classic Tolstoyan old farmer in a white peasant smock stepped forward to cry out that everything the foreigners were being shown was false, that life under Communism was terrible, and that they must go back to Britain and tell the truth. Lessing now calls this the bravest act she had ever witnessed, since the old man had to know that “he would be arrested and disposed of.” It is unclear how much she herself knew or was willing to know at the time. After a banquet and a viewing of “presents to Stalin from his grateful subjects,” she went to sit outside, alone, and brood. And it was apparently her shame over her aesthetic revulsion at those hideous presents—mostly boxes and rugs featuring Stalin’s carved or woven face that led her to the macabre conclusion of this episode: her decision to write a story “according to the communist formula.”

Insisting on one’s belief in the face of all evidence; seeing and hearing what you need to be true instead of what, horribly, is; hanging on to what you know you cannot live without. And then letting it go. This memoir—like “The Golden Notebook”—is about the admission of colossal, sickening error and defeat. “All around me,” Lessing recalls, “people’s hearts were breaking, they were having breakdowns, they were suffering religious conversions” over the collapse of Communism as a moral force. She points almost gratefully to one of the century’s awful paradoxes: that, while the politically negligent helped make Hitler possible, it was “the most sensitive, compassionate, socially concerned people” who did the same for Stalin. This is not offered as a defense, exactly, but as evidence of a kind of mass delusion, in which the only imperative was to believe in something larger than the single self.

“Losing faith in communism is exactly paralleled by people in love who cannot let their dream of love go,” Lessing writes. For her, the comparison is not abstract. She suffered two disastrous love affairs during the years covered here, long affairs that were more marriages than her marriages had been, and that left her feeling misused, empty, and nearly out of her mind with misery. In fact, she was misused, as she reports it—both here and, in far more excruciating detail, in “The Golden Notebook.” She was lonely and in need and had read far too much D. H. Lawrence. But she was also a modern woman: she wasn’t going to ask for anything that would make her seem wanting or weak. And the very modern “men-babies” that the age was producing certainly weren’t going to give anything—there were now spoken rules about this—even as they pillaged her emotional store and absorbed all the loving and the cooking and the nursing and the sex that any sensible Victorian woman would have set at a far higher market price. No wonder she felt empty by the time they were sated and moved on.

“Sometimes I think we’re all in a sort of sexual mad house,” one of the shell-shocked women in “The Golden Notebook” remarks. “My dear,” a friend replies, “we’ve chosen to be free women and this is the price we pay.” As it happens, “Free Women” is the title of a book that Anna Wulf begins writing, and it is meant to be ironic. Lessing’s women are not only willfully blind in their romantic delusions but—and this is the price they pay—deprived of any further use of their corrupted and exhausted wills. Like Lessing in her memoir, they have descended to the level where accepting pain is easier than taking responsibility.

What is most ironic of all, perhaps, is that “The Golden Notebook” has entered literary history as, in Lessing’s words, the “Bible of the Women’s Movement”—the novel that introduced the subject of women’s liberation to American society. Lessing herself seems torn between laughter and tears at the thought. It is clearly her searching, shameless honesty that readers responded to so avidly; women had never talked like this in print before. But as a document of liberation her book may be classed with Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex” (which in 1949 announced the “free woman” as a type just being born) and with Richard Wright’s “Native Son.” All three are works in which the angry subject is such a crippled specimen that hope and progress can be detected primarily in the sheer, howling relief of the author’s declaration: If I am a monster, it is because you have made me one.

Lessing’s heroines tend to break down completely before they are able to put themselves back together—perhaps on the Marxist model that revolution must precede utopia. The author informs us that she herself managed to escape real breakdown through writing about it. Through psychoanalysis, she came to understand that even her support of the Soviet Union was “only a continuation of early childhood feelings,” primarily suffering and identification with pain. In Africa, in a house with mud walls and Liberty curtains, her mother had complained bitterly of the sacrifice of her own talents to the raising of two children. Lessing’s strikingly exact reversal of that sacrifice did not ease the weight she carried. In her earlier memoir she skips ahead to let us know that her firstborn son, when a middle-aged man, told her that he understood why she’d had to leave his father, but that he still resented it. Her need to save the world—so much better an excuse for running off than domestic restlessness or the desire to write stories and novels—is not mentioned. Both this crusade and its failure, however, may help to explain why her stories and novels had to take on that moral burden.

But this isn’t why they are worth reading. For all her theories and her ethics and the range of her literary personae—the African realist, the London scene painter, the anguished psychologist, the science-fiction galaxy roamer turning out volumes on “the fate of the universe”—Lessing’s rarest gift is for getting characters on their feet and setting the wind stirring the curtains with language so apparently simple it betrays no method at all. Many of the short stories, in particular, seem to have written themselves. “Homage for Isaac Babel” renders adolescent tenderness and the psychology of literary style in three perfect pages; “The Day Stalin Died” and “How I Finally Lost My Heart” divide the weighty themes of “The Golden Notebook” and release them like birds into the air. The classical concision of the form seems to induce in Lessing a kind of clear-eyed mental energy, an urge to pick the locks of the elaborate cages she builds in her novels.

It’s possible that what makes Lessing so fascinating a writer is the skewed alignment of her vision and her gifts. Here is a utopian humanist who cannot help seeing into the mixed and muddled cores of actual people; an apocalyptic town crier who is also one of modern fiction’s most precise domestic realists—a Pieter de Hooch who can suddenly flare into Bosch. True, it can sometimes seem that apocalypse is merely her requirement for making a decision. (When a world is ending, it is surely time to pack your bags.) But the woman who now claims in her memoirs to have been borne through much of her life upon the tides of history, helpless and passive, has written a stack of books that entirely contradict this notion—books that are nothing if not the product of a hugely stubborn and struggling soul.

“I have to conclude that fiction is better at ‘the truth’ than a factual record,” Lessing surmised in a new introduction to “The Golden Notebook,” in 1993. As is true of most writers’ memoirs, Lessing’s are secondary events, their unvarnished truths of special interest only because of the beautifully painted half truths that have gained a hold on our imaginations. But with Lessing the usual paradox only begins here, for the fiction that details her personal and political failures also embodies her creative triumphs. “The Golden Notebook” may be a monument to disillusion and despair, but it remains a monument—one that stands for an era of formidable transition. At its end, Anna Wulf pulls herself together, joins the Labour Party, and begins to do volunteer work to ease her need to make all things better than they ever can be. Her steps seem small, sad, and honest. At the same point of emotional recovery in “Walking in the Shade,” Lessing announces a newfound allegiance to Sufism, and the reader almost sighs at the sound of the authorial boots tramping off uphill again, in this spiralling Pilgrim’s Progress of a life.

In a time with so little faith in the achievement of higher destinations, it is surely Lessing’s ability to hold fast to her goal even as she records every stumble and collapse along the way which has made her work of near-inspirational value to so many. Oddly, Lessing the memoirist is unable to acknowledge this dual aspect of her appeal, and ends by belittling her own contribution. In “Walking in the Shade” she pronounces “The Golden Notebook” to be a failure, on the ground that even this most influential of her books hasn’t really changed the way people think. Characteristically, the standards of judgment expressed in her fiction are more reasonable, even more forgiving.

In a slender novel called “The Memoirs of a Survivor,” written in 1974 and called by the author “an attempt at autobiography,” Lessing fused all her visions and gifts into a single ravishing fable. Set on several levels of reality, it tells of a woman who is mysteriously entrusted with a child to care for just as the civilization around her crashes down. Despite its fantastic elements, the tone is natural, the people are true, the language is taut and glowing. Near the end, the woman sits in the ruins of a London-like city and pictures a garden that is now out of reach, a place she visited briefly and believes that people will return to someday. “It was hard to maintain a knowledge of that other world, with its scents and running waters and its many plants, while I sat here in this dull shabby daytime room,” she recalls. But then she goes on to assert, with quiet pride, just what Lessing might rightly claim for herself: “I did hold it. I kept it in my mind. I was able to do this.” ♦

Published in the print edition of the November 17, 1997, issue.

Claudia Roth Pierpont has contributed to The New Yorker since 1990 and became a staff writer in 2004.

****

Jean Gee was there at the start with Ann Cryer. Now 77, the former social worker helped to introduce the MP to the victims’ mothers in 2002. “I used to work with kids who were excluded from school,” she tells me. “And I’d see first-hand how they were picked up by men in their taxis.” At the time, Jean didn’t know that one of the girls would be a close family member.

Amber* was raped just over a decade ago by a man she believed was a friend of her father’s. Unlike a number of the town’s victims, who have left, fearful that their attackers still walk its streets, Amber still lives in Keighley. Every day is a reminder of her trauma. She suffers from a severe eating disorder that has left her unable to have children. Her body is skeletal, her arms tattooed. “It marks a girl for life,” Jean says.

Around the same time as Amber was being groomed, a gang of 12 men were targeting a 13-year-old girl, Autumn*. The torment she would endure — over 13 months between 2011 and 2012 — would become Keighley’s darkest chapter. During one incident, she was gang-raped by five men; during another, she was raped in an underground car park next to a wall brazenly graffitied with the names of some of her attackers.

In 2016, Autumn’s 12 attackers were convicted — and the judge found she’d been failed by police and social workers. After one attack, officers dismissed her as a prostitute; after another, they failed to progress a medical assessment. As for her abusers, the judge concluded that “they saw her as a pathetic figure who… served no purpose than to be an object that they could sexually misuse and cast aside”. In their mugshots, two of her attackers are smiling.

Autumn’s younger brother, Adam*, now in his early 20s, believes the past fortnight’s debate over grooming gangs is fuelled by hypocrisy. “Politicians of all stripes colluded with the police to engage in a cover-up,” he tells me. He blames the Conservative Party for “failing to act on this issue despite so many cases occurring under them”. And he blames Labour, whose leader this week suggested it was a “far-Right” issue, despite the “most impacted areas being run by that party”. Meanwhile, Nigel Farage’s Reform — which registered 10% of the vote in Keighley in last year’s general election, well below its national average — is also trying to make political hay. “At least the SDP here have always prioritised the issue of grooming gangs,” he says. As for Elon Musk, who described Labour MP Jess Phillips as a “rape genocide apologist” and called for Tommy Robinson to be released from prison, Adam views him as “clearly unstable” but welcomes his intervention. “Anything that brings attention to this issue is good,” he says.

Back in town, though, most are oblivious to this week’s political mudslinging, which culminated on Wednesday in a failed Conservative vote to force a new inquiry. Few of those I speak to — Pakistani and white, young and old — are aware of Musk’s recent comments. “If Tommy Robinson came to Keighley, he’d get beaten up,” says one white woman in her early-20s. “When will [Pretoria-born] Musk start tweeting about South Africa’s race problems?” jokes one bemused madrasah teacher.

There’s a similar lack of consensus over calls for a new inquiry into West Yorkshire’s grooming gangs. This is partly because people doubt its sincerity; neither the Conservatives nor Reform mentioned an inquiry in last year’s manifestos. But it’s mostly because few believe another investigation will be acted upon. “What would the value be?” says Gee, who voted Conservative last year. “How likely is it that something will happen? It’s not as if we have the money to change anything. Just look at our housing and social care system.”

Even Adam has his reservations. “What comes after? We need to deal with the source and not just address the past.” Typical was one stallholder in Keighley’s indoor market. “I know I’d feel different if my daughter was one of the victims,” she said, “but I don’t think it’s a priority now.” Keighley, she points out, may be pretty — but it isn’t thriving. In some neighbourhoods, 40% of households are classified as deprived.

Still, there are attempts to learn from the past. After school, youth workers patrol the shopping centre and adjoining bus station where many of the town’s victims were once ensnared. “There are still creeps around,” says one teenage girl. “But they’re not just Pakistani. To be honest, they’re more likely to be a 60-year-old white guy.”

There are those, however, who remain concerned that former groomers have gone unpunished. After all, if Cryer and those seven mothers were correct, and there were at least 35 offenders in the town, not all have been caught. “Membership of these gangs is informal and often it’s hard to pin down members,” says Adam, who still believes the abusers walk the town’s streets. “You also can’t blame girls who haven’t come forward given the police’s previous failures.” Jean agrees, though also believes many “grooming gangs” have been replaced by county lines gangs, whose members are both Pakistani and white. Just this month, more than 50 members of one such gang in Keighley — peddling heroin and crack cocaine — were arrested by police.

But such developments don’t fit into the narrative of Britain’s national debate — a binary war, fought mostly online, between those uncomfortable with highlighting the ethnicity of West Yorkshire’s grooming gangs and those who seek to exploit it. Meanwhile, the affected communities are viewed as collateral. As one fed up local told me: “We’ve got enough wars going on without your Tommy Robinsons starting another.”

In Keighley, few are worried about the return of the far-Right. Their Conservative MP, Robbie Moore, has been outspoken about the need for another inquiry, neutralising movements further to the Right. In 2017, the EDL tried to hold a protest in the town and were outnumbered by police. But there’s still disquiet. In 2022, three members of a neo-Nazi cell in Keighley were jailed after being caught buying a 3D printer to make a gun. The following year, a teenager was jailed after he planned to attack one of the town’s mosques while disguised as an armed police officer.

Nor has faith in its institutions been restored. Last November, the town was left horrified when a local police officer was jailed for having sex with a vulnerable domestic abuse victim whose complaints he had been tasked with investigating. When I asked West Yorkshire Police how it hopes to regain Keighley’s trust after decades of neglect, I was told the officer’s “offending was not connected to grooming gangs” and redirected to an old press release.

But it feels connected, feeding into a pattern of betrayal. Despite the best efforts of a noble MP, Keighley remains a case study in exploitation — first by a terrified establishment who ignored the abuse of the town’s young girls, and then by a far-Right menace who sought to capitalise on their cowardice. And now, as attempts are made to reheat their trauma, Keighley’s residents might be forgiven for their ambivalence. They’ve seen this before, and know how it ends. The fires of our digital ecosystem will consume its subjects. But in Keighley, cold resignation preserves them.

*Names have been changed

Jacob Furedi is

***

Dylan

Will Stenberg ·

Follow

oodenpstSre0m0325reuht4gl:4ct64a m8870u1c3cg9e2bht2 g0uDg037c ·

Alright, so I just saw the Bob Dylan movie. Some context: Bob Dylan is my favorite artist, in any medium, ever. Period. I'm not saying he's better than your favorite. Just, for me, he's the guy, in a profound way that's hard to articulate.

I'm one of those insufferable Bob Dylan nerds. I come to it naturally: my father is a Dylan bootleg collector who could easily, for instance, make you a playlist of 500 different renditions of "Like a Rolling Stone." As for me I can make the case that his 1983 album "Infidels" would be up there with "Blood on the Tracks" if he'd subbed out some of the official tracklist for outtakes (drop "Neighborhood Bully" and "Union Sundown," add "Blind Willie McTell" and "Lord Protect My Child" and, while you're at it, grab "Angelina" from the "Shot of Love" sessions; now you have a masterpiece). And that's just surface-level stuff.

I'm one of those guys - one of those who cringes when people make fun of his voice because it tends to show that they think his "Blonde on Blonde" vocal style was emblematic of his career when in fact very few popular singers have changed singing styles as often or as brazenly as Dylan; the type of fan who listens to his modern output as much as anything else and has seen him in concert many times and knows his interviews almost as well as his songs.

So, the movie was an experience.

In a way, it's impossible to make a movie about Bob Dylan because it's like taking a still picture of a kaleidoscope: the resulting impression will be inevitably deceptive. Todd Haynes knew this when he made "I'm Not There," but that was the right approach with a very uneven execution, as memorable as Cate Blanchett was in her segment. The perfect Dylan biopic, if such a thing is conceivable, might be some kind of middle ground between "A Complete Unknown" and the Haynes pic.

Anyway. This movie. I don't really care about the inaccuracies. They are abundant; too many to go over. As a screenwriter myself, a lot of them are forgivable. Lives don't play out like movies, with all the right beats falling into a Three Act structure, so if you're making a film from reality you can't escape playing with facts, molding the chaos of actual life into the form of a film.

For example, Johnny Cash was not at the Newport Fest where Dylan "went electric"; he was, however, a really vocal advocate of Dylan's transformation and gave him crucial encouragement to follow his muse. But it played out mostly in letters, which are shown in the movie but aren't very cinematic. So, you put him at Newport - he wasn't there in '65, but he was there in '64. Close enough. It's not really a lie; rather it is taking some truths (Cash played Newport, Cash defended Dylan) and finding a way to combine them that portrays Cash's advocacy dramatically. That's how you write a biopic.

I won't defend all the changes - I think the first meeting with Woody would play a lot more powerfully as it happened, without Pete Seeger present - but I'm just saying that I understand what was going on in principle.

The other thing is that Dylan obfuscates his own life and past to such a degree that any Dylan movie that is too faithful to the truth just wouldn't be Dylanesque. He's still doing this. Casual fans might not be aware, but the Netflix Martin Scorsese documentary on The Rolling Thunder Revue is full of mistruths, put in at Dylan's request, including actors portraying fictional interview subjects. At one point, Sharon Stone says she was with the tour as an underage groupie - she was not - which shows that Dylan will even lie in such a way that it makes him look bad, as long as it throws people off the trail. Those of us who are acolytes admire that about him, perversely or otherwise.

Okay, so, how was the movie? Fairly conventional, as one might expect from Mangold. Full of masterful performances, though they come off more often than not as highly-skilled impersonations rather than embodiments or impressionistic riffs, an approach which might be more suited to the subject, if not the tone, of the film.

Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez is superb. If she fails to fully capture the icy perfection of Joan's singing, that's not a knock - few can. (On the other hand, she nailed a really underrated facet of Joan's artistry - that she's a killer guitar player.) I don't know what Joan Baez was like in private in the 60s, but her performance also showcased a bit of the salty, foul-mouthed, free-spirited Baez we've seen in interviews since the turn of the century, who is a lot more fun-loving and relatable than the sometimes sanctimonious and overly pious folk goddess of the 60s. Barbaro's performance made me believe that Joan has always been both, which is probably true.

Speaking of pious, Norton's Pete Seeger might be the most pitch-perfect impression. I was able to suspend my disbelief most closely with his performance, so attuned was he to that collegiate mid-Atlantic accent, ramrod posture and seemingly unflappable demeanor (though they really kind of had it both ways with the infamous axe incident; I wanted to see Pete Hulk out as per the legend). The Pete Seeger I saw in the movie was exactly like the Pete Seeger of real life, in my humble opinion: artistically boring and ethically unimpeachable.

Elle Fanning was great, but her part was thin and mostly served as a foil to Chalamet. That's one point where a weak script showed through; another was some of the ridiculously expository dialogue (as Bob launches into "Like a Rolling Stone" in the studio, an engineer says something like, "Ooh boy, people aren't going to like this").

As for Timmy, I can't take anything away from him. It struck me as the impression of an excellent technician rather than a deep embodiment, but I don't think the script allowed for more. He did great. Particularly when he dons the dark glasses and high fashion, I caught glimpses of the real Dylan. (The 19 year-old Dyan who first came to New York and made that record was still very baby-faced so seeing the waifish Chalomet in this period was surreal, like the '65 Bob doing an impression of his own childhood.)

There are some reviews out there complaining that we never get to know who the "real" Bob Dylan is, why he's writing these songs, or what he wants. That's fine with me. We don't know that in real life and any film that tried to make a thesis statement on this subject would be making a crucial mistake. And, yes, Dylan's reputation as "kind of an asshole" is portrayed without a lot of caveats - arguably to Bob's credit, since he reviewed the script - although I will say that this knock on Bob is mostly down to him being rude and kind of careerist whereas there is shit about his contemporaries that is actually nefarious and criminal, so I'm not sure why he gets singled out.

Maybe a nitpick of mine would be how wishy-washy the script is about to what extent Dylan believed in the movements that adopted his songs and offered him a figurehead position that he ultimately rejected. There's literally no point where you see him talk about politics or racial justice, but, like, the guy went to Mississippi at a time when it was possible to be yanked off a bus and found in a ditch with the back of your head blown off for doing so. A lot of people didn't go; Bob did. He "opened" for MLK before the "I Have a Dream Speech." The movie shows this - in a montage, and further removed by taking place on a television screen.

In my view, Dylan rejected the mantle of spokesperson and the rigidity of ideological constraints on his artistic vision - and more power to him - but I don't think his participation was insincere. The film doesn't take a stand on this one way or another, and that felt a little off, like they were afraid of offering a perspective. But it's a hard topic to avoid given the years they decided to cover, and I'd rather they'd disagreed with my take than just refuse to have one.

On this topic, I always like to mention that there's an issue of Esquire Magazine from 1965 that features a facial conglomeration of JFK, Fidel Castro, Malcom X and ... Bob Dylan, a young guy who writes songs. When I see this, I get a visceral sense of the absolute dread that must have gripped the heart of someone who was essentially a middle-class Midwestern Jewish kid who happened to be possessed by artistic genius. He was being asked to die, by people who didn't even know him, and from this perspective I think his supposedly callous treatment of folks in the movement who refused to let him go feels more like the panic of self-preservation.

Anyway, that's a tangent. How was the movie? Fine. They made one really good decision: they put a ton of focus on the music, which is ultimately what matters. And Timmy did an incredible vocal impersonation of Dylan's singing at this juncture: the knife-like nasality that jumped through the speakers and forced you to listen; the weird flattened Midwest vowels filtered through an Okie impersonation; the deliberate articulation of each syllable like a judge pounding a gavel. He really nailed that.

It was good to begin and end with Woody, too. For all of the young Dylan's rudeness and ruthlessness, those visits showed "Another Side of Bob Dylan," as the record would be called. Not everyone in the folk scene was crossing the river to that grim place to spend time with a very sick man who could give nothing in return. And Bob wasn't inviting press to these things; we only know because he became famous. Those visits showed Bob Dylan's sense of the sacred which is ultimately what he has sought to preserve from anyone who would attempt to control or confine it, throughout all the years, eras and masks.

The young man who saw saw "a black branch with blood that kept drippin’," "a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’," "a white ladder all covered with water," and "ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken" isn't someone who can be portrayed onscreen because he exists in the interior, not the exterior, of the self. This is ultimately why biopics about artists are so difficult: that what we most admire about them - their art - comes from a place where cameras can't go, and Bob Dylan has spent more time there than most people who have ever lived.

pg

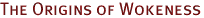

woke

January 2025

The word "prig" isn't very common now, but if you look up the definition, it will sound familiar. Google's isn't bad:

A self-righteously moralistic person who behaves as if superior to others.

This sense of the word originated in the 18th century, and its age is an important clue: it shows that although wokeness is a comparatively recent phenomenon, it's an instance of a much older one.

There's a certain kind of person who's attracted to a shallow, exacting kind of moral purity, and who demonstrates his purity by attacking anyone who breaks the rules. Every society has these people. All that changes is the rules they enforce. In Victorian England it was Christian virtue. In Stalin's Russia it was orthodox Marxism-Leninism. For the woke, it's social justice.

So if you want to understand wokeness, the question to ask is not why people behave this way. Every society has prigs. The question to ask is why our prigs are priggish about these ideas, at this moment. And to answer that we have to ask when and where wokeness began.

The answer to the first question is the 1980s. Wokeness is a second, more aggressive wave of political correctness, which started in the late 1980s, died down in the late 1990s, and then returned with a vengeance in the early 2010s, finally peaking after the riots of 2020.

(AA Gill on PC versus Wales and Claire Balding)

This was not the original meaning of woke, but it's rarely used in the original sense now. Now the pejorative sense is the dominant one. What does it mean now? I've often been asked to define both wokeness and political correctness by people who think they're meaningless labels, so I will. They both have the same definition:

An aggressively performative focus on social justice.

In other words, it's people being prigs about social justice. And that's the real problem — the performativeness, not the social justice.

Racism, for example, is a genuine problem. Not a problem on the scale that the woke believe it to be, but a genuine one. I don't think any reasonable person would deny that. The problem with political correctness was not that it focused on marginalized groups, but the shallow, aggressive way in which it did so. Instead of going out into the world and quietly helping members of marginalized groups, the politically correct focused on getting people in trouble for using the wrong words to talk about them.

As for where political correctness began, if you think about it, you probably already know the answer. Did it begin outside universities and spread to them from this external source? Obviously not; it has always been most extreme in universities. So where in universities did it begin? Did it begin in math, or the hard sciences, or engineering, and spread from there to the humanities and social sciences? Those are amusing images, but no, obviously it began in the humanities and social sciences.

Why there? And why then? What happened in the humanities and social sciences in the 1980s?

A successful theory of the origin of political correctness has to be able to explain why it didn't happen earlier. Why didn't it happen during the protest movements of the 1960s, for example? They were concerned with much the same issues. [1]

The reason the student protests of the 1960s didn't lead to political correctness was precisely that — they were student movements. They didn't have any real power. The students may have been talking a lot about women's liberation and black power, but it was not what they were being taught in their classes. Not yet.

But in the early 1970s the student protestors of the 1960s began to finish their dissertations and get hired as professors. At first they were neither powerful nor numerous. But as more of their peers joined them and the previous generation of professors started to retire, they gradually became both.

The reason political correctness began in the humanities and social sciences was that these fields offered more scope for the injection of politics. A 1960s radical who got a job as a physics professor could still attend protests, but his political beliefs wouldn't affect his work. Whereas research in sociology and modern literature can be made as political as you like. [2]

I saw political correctness arise. When I started college in 1982 it was not yet a thing. Female students might object if someone said something they considered sexist, but no one was getting reported for it. It was still not a thing when I started grad school in 1986. It was definitely a thing in 1988 though, and by the early 1990s it seemed to pervade campus life.

What happened? How did protest become punishment? Why were the late 1980s the point at which protests against male chauvinism (as it used to be called) morphed into formal complaints to university authorities about sexism? Basically, the 1960s radicals got tenure. They became the Establishment they'd protested against two decades before. Now they were in a position not just to speak out about their ideas, but to enforce them.

A new set of moral rules to enforce was exciting news to a certain kind of student. What made it particularly exciting was that they were allowed to attack professors. I remember noticing that aspect of political correctness at the time. It wasn't simply a grass-roots student movement. It was faculty members encouraging students to attack other faculty members. In that respect it was like the Cultural Revolution. That wasn't a grass-roots movement either; that was Mao unleashing the younger generation on his political opponents. And in fact when Roderick MacFarquhar started teaching a class on the Cultural Revolution at Harvard in the late 1980s, many saw it as a comment on current events. I don't know if it actually was, but people thought it was, and that means the similarities were obvious. [3]

College students larp. It's their nature. It's usually harmless. But larping morality turned out to be a poisonous combination. The result was a kind of moral etiquette, superficial but very complicated. Imagine having to explain to a well-meaning visitor from another planet why using the phrase "people of color" is considered particularly enlightened, but saying "colored people" gets you fired. And why exactly one isn't supposed to use the word "negro" now, even though Martin Luther King used it constantly in his speeches. There are no underlying principles. You'd just have to give him a long list of rules to memorize. [4]

The danger of these rules was not just that they created land mines for the unwary, but that their elaborateness made them an effective substitute for virtue. Whenever a society has a concept of heresy and orthodoxy, orthodoxy becomes a substitute for virtue. You can be the worst person in the world, but as long as you're orthodox you're better than everyone who isn't. This makes orthodoxy very attractive to bad people.

But for it to work as a substitute for virtue, orthodoxy must be difficult. If all you have to do to be orthodox is wear some garment or avoid saying some word, everyone knows to do it, and the only way to seem more virtuous than other people is to actually be virtuous. The shallow, complicated, and frequently changing rules of political correctness made it the perfect substitute for actual virtue. And the result was a world in which good people who weren't up to date on current moral fashions were brought down by people whose characters would make you recoil in horror if you could see them.

One big contributing factor in the rise of political correctness was the lack of other things to be morally pure about. Previous generations of prigs had been prigs mostly about religion and sex. But among the cultural elite these were the deadest of dead letters by the 1980s; if you were religious, or a virgin, this was something you tended to conceal rather than advertise. So the sort of people who enjoy being moral enforcers had become starved of things to enforce. A new set of rules was just what they'd been waiting for.

Curiously enough, the tolerant side of the 1960s left helped create the conditions in which the intolerant side prevailed. The relaxed social rules advocated by the old, easy-going hippy left became the dominant ones, at least among the elite, and this left nothing for the naturally intolerant to be intolerant about.

Another possibly contributing factor was the fall of the Soviet empire. Marxism had been a popular focus of moral purity on the left before political correctness emerged as a competitor, but the pro-democracy movements in Eastern Bloc countries took most of the shine off it. Especially the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. You couldn't be on the side of the Stasi. I remember looking at the moribund Soviet Studies section of a used bookshop in Cambridge in the late 1980s and thinking "what will those people go on about now?" As it turned out the answer was right under my nose.

One thing I noticed at the time about the first phase of political correctness was that it was more popular with women than men. As many writers (perhaps most eloquently George Orwell) have observed, women seem more attracted than men to the idea of being moral enforcers. But there was another more specific reason women tended to be the enforcers of political correctness. There was at this time a great backlash against sexual harassment; the mid 1980s were the point when the definition of sexual harassment was expanded from explicit sexual advances to creating a "hostile environment." Within universities the classic form of accusation was for a (female) student to say that a professor made her "feel uncomfortable." But the vagueness of this accusation allowed the radius of forbidden behavior to expand to include talking about heterodox ideas. Those make people uncomfortable too. [5]

Was it sexist to propose that Darwin's greater male variability hypothesis might explain some variation in human performance? Sexist enough to get Larry Summers pushed out as president of Harvard, apparently. One woman who heard the talk in which he mentioned this idea said it made her feel "physically ill" and that she had to leave halfway through. If the test of a hostile environment is how it makes people feel, this certainly sounds like one. And yet it does seem plausible that greater male variability explains some of the variation in human performance. So which should prevail, comfort or truth? Surely if truth should prevail anywhere, it should be in universities; that's supposed to be their specialty; but for decades starting in the late 1980s the politically correct tried to pretend this conflict didn't exist. [6]

Political correctness seemed to burn out in the second half of the 1990s. One reason, perhaps the main reason, was that it literally became a joke. It offered rich material for comedians, who performed their usual disinfectant action upon it. Humor is one of the most powerful weapons against priggishness of any sort, because prigs, being humorless, can't respond in kind. Humor was what defeated Victorian prudishness, and by 2000 it seemed to have done the same thing to political correctness.

Unfortunately this was an illusion. Within universities the embers of political correctness were still glowing brightly. After all, the forces that created it were still there. The professors who started it were now becoming deans and department heads. And in addition to their departments there were now a bunch of new ones explicitly focused on social justice. Students were still hungry for things to be morally pure about. And there had been an explosion in the number of university administrators, many of whose jobs involved enforcing various forms of political correctness.

In the early 2010s the embers of political correctness burst into flame anew. There were several differences between this new phase and the original one. It was more virulent. It spread further into the real world, although it still burned hottest within universities. And it was concerned with a wider variety of sins. In the first phase of political correctness there were really only three things people got accused of: sexism, racism, and homophobia (which at the time was a neologism invented for the purpose). But between then and 2010 a lot of people had spent a lot of time trying to invent new kinds of -isms and -phobias and seeing which could be made to stick.

The second phase was, in multiple senses, political correctness metastasized. Why did it happen when it did? My guess is that it was due to the rise of social media, particularly Tumblr and Twitter, because one of the most distinctive features of the second wave of political correctness was the cancel mob: a mob of angry people uniting on social media to get someone ostracized or fired. Indeed this second wave of political correctness was originally called "cancel culture"; it didn't start to be called "wokeness" till the 2020s.

One aspect of social media that surprised almost everyone at first was the popularity of outrage. Users seemed to like being outraged. We're so used to this idea now that we take it for granted, but really it's pretty strange. Being outraged is not a pleasant feeling. You wouldn't expect people to seek it out. But they do. And above all, they want to share it. I happened to be running a forum from 2007 to 2014, so I can actually quantify how much they want to share it: our users were about three times more likely to upvote something if it outraged them.

This tilt toward outrage wasn't due to wokeness. It's an inherent feature of social media, or at least this generation of it. But it did make social media the perfect mechanism for fanning the flames of wokeness. [7]

It wasn't just public social networks that drove the rise of wokeness though. Group chat apps were also critical, especially in the final step, cancellation. Imagine if a group of employees trying to get someone fired had to do it using only email. It would be hard to organize a mob. But once you have group chat, mobs form naturally.

Another contributing factor in this second wave of political correctness was the dramatic increase in the polarization of the press. In the print era, newspapers were constrained to be, or at least seem, politically neutral. The department stores that ran ads in the New York Times wanted to reach everyone in the region, both liberal and conservative, so the Times had to serve both. But the Times didn't regard this neutrality as something forced upon them. They embraced it as their duty as a paper of record — as one of the big newspapers that aimed to be chronicles of their times, reporting every sufficiently important story from a neutral point of view.

When I grew up the papers of record seemed timeless, almost sacred institutions. Papers like the New York Times and Washington Post had immense prestige, partly because other sources of news were limited, but also because they did make some effort to be neutral.

Unfortunately it turned out that the paper of record was mostly an artifact of the constraints imposed by print. [8] When your market was determined by geography, you had to be neutral. But publishing online enabled — in fact probably forced — newspapers to switch to serving markets defined by ideology instead of geography. Most that remained in business fell in the direction they'd already been leaning: left. On October 11, 2020 the New York Times announced that "The paper is in the midst of an evolution from the stodgy paper of record into a juicy collection of great narratives." [9] Meanwhile journalists, of a sort, had arisen to serve the right as well. And so journalism, which in the previous era had been one of the great centralizing forces, now became one of the great polarizing ones.

The rise of social media and the increasing polarization of journalism reinforced one another. In fact there arose a new variety of journalism involving a loop through social media. Someone would say something controversial on social media. Within hours it would become a news story. Outraged readers would then post links to the story on social media, driving further arguments online. It was the cheapest source of clicks imaginable. You didn't have to maintain overseas news bureaus or pay for month-long investigations. All you had to do was watch Twitter for controversial remarks and repost them on your site, with some additional comments to inflame readers further.

For the press there was money in wokeness. But they weren't the only ones. That was one of the biggest differences between the two waves of political correctness: the first was driven almost entirely by amateurs, but the second was often driven by professionals. For some it was their whole job. By 2010 a new class of administrators had arisen whose job was basically to enforce wokeness. They played a role similar to that of the political commissars who got attached to military and industrial organizations in the USSR: they weren't directly in the flow of the organization's work, but watched from the side to ensure that nothing improper happened in the doing of it. These new administrators could often be recognized by the word "inclusion" in their titles. Within institutions this was the preferred euphemism for wokeness; a new list of banned words, for example, would usually be called an "inclusive language guide." [10]

This new class of bureaucrats pursued a woke agenda as if their jobs depended on it, because they did. If you hire people to keep watch for a particular type of problem, they're going to find it, because otherwise there's no justification for their existence. [11] But these bureaucrats also represented a second and possibly even greater danger. Many were involved in hiring, and when possible they tried to ensure their employers hired only people who shared their political beliefs. The most egregious cases were the new "DEI statements" that some universities started to require from faculty candidates, proving their commitment to wokeness. Some universities used these statements as the initial filter and only even considered candidates who scored high enough on them. You're not hiring Einstein that way; imagine what you get instead.

Another factor in the rise of wokeness was the Black Lives Matter movement, which started in 2013 when a white man was acquitted after killing a black teenager in Florida. But this didn't launch wokeness; it was well underway by 2013.

Similarly for the Me Too Movement, which took off in 2017 after the first news stories about Harvey Weinstein's history of raping women. It accelerated wokeness, but didn't play the same role in launching it that the 80s version did in launching political correctness.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 also accelerated wokeness, particularly in the press, where outrage now meant traffic. Trump made the New York Times a lot of money: headlines during his first administration mentioned his name at about four times the rate of previous presidents.

In 2020 we saw the biggest accelerant of all, after a white police officer asphyxiated a black suspect on video. At this point the metaphorical fire became a literal one, as violent protests broke out across America. But in retrospect this turned out to be peak woke, or close to it. By every measure I've seen, wokeness peaked in 2020 or 2021.

Wokeness is sometimes described as a mind-virus. What makes it viral is that it defines new types of impropriety. Most people are afraid of impropriety; they're never exactly sure what the social rules are or which ones they might be breaking. Especially if the rules change rapidly. And since most people already worry that they might be breaking rules they don't know about, if you tell them they're breaking a rule, their default reaction is to believe you. Especially if multiple people tell them. Which in turn is a recipe for exponential growth. Zealots invent some new impropriety to avoid. The first people to adopt it are fellow zealots, eager for new ways to signal their virtue. If there are enough of these, the initial group of zealots is followed by a much larger group, motivated by fear. They're not trying to signal virtue; they're just trying to avoid getting in trouble. At this point the new impropriety is now firmly established. Plus its success has increased the rate of change in social rules, which, remember, is one of the reasons people are nervous about which rules they might be breaking. So the cycle accelerates. [12]

What's true of individuals is even more true of organizations. Especially organizations without a powerful leader. Such organizations do everything based on "best practices." There's no higher authority; if some new "best practice" achieves critical mass, they must adopt it. And in this case the organization can't do what it usually does when it's uncertain: delay. It might be committing improprieties right now! So it's surprisingly easy for a small group of zealots to capture this type of organization by describing new improprieties it might be guilty of. [13]

How does this kind of cycle ever end? Eventually it leads to disaster, and people start to say enough is enough. The excesses of 2020 made a lot of people say that.

Since then wokeness has been in gradual but continual retreat. Corporate CEOs, starting with Brian Armstrong, have openly rejected it. Universities, led by the University of Chicago and MIT, have explicitly confirmed their commitment to free speech. Twitter, which was arguably the hub of wokeness, was bought by Elon Musk in order to neutralize it, and he seems to have succeeded — and not, incidentally, by censoring left-wing users the way Twitter used to censor right-wing ones, but without censoring either. [14] Consumers have emphatically rejected brands that ventured too far into wokeness. The Bud Light brand may have been permanently damaged by it. I'm not going to claim Trump's second victory in 2024 was a referendum on wokeness; I think he won, as presidential candidates always do, because he was more charismatic; but voters' disgust with wokeness must have helped.

So what do we do now? Wokeness is already in retreat. Obviously we should help it along. What's the best way to do that? And more importantly, how do we avoid a third outbreak? After all, it seemed to be dead once, but came back worse than ever.

In fact there's an even more ambitious goal: is there a way to prevent any similar outbreak of aggressively performative moralism in the future — not just a third outbreak of political correctness, but the next thing like it? Because there will be a next thing. Prigs are prigs by nature. They need rules to obey and enforce, and now that Darwin has cut off their traditional supply of rules, they're constantly hungry for new ones. All they need is someone to meet them halfway by defining a new way to be morally pure, and we'll see the same phenomenon again.

Let's start with the easier problem. Is there a simple, principled way to deal with wokeness? I think there is: to use the customs we already have for dealing with religion. Wokeness is effectively a religion, just with God replaced by protected classes. It's not even the first religion of this kind; Marxism had a similar form, with God replaced by the masses. [15] And we already have well-established customs for dealing with religion within organizations. You can express your own religious identity and explain your beliefs, but you can't call your coworkers infidels if they disagree, or try to ban them from saying things that contradict its doctrines, or insist that the organization adopt yours as its official religion.

If we're not sure what to do about any particular manifestation of wokeness, imagine we were dealing with some other religion, like Christianity. Should we have people within organizations whose jobs are to enforce woke orthodoxy? No, because we wouldn't have people whose jobs were to enforce Christian orthodoxy. Should we censor writers or scientists whose work contradicts woke doctrines? No, because we wouldn't do this to people whose work contradicted Christian teachings. Should job candidates be required to write DEI statements? Of course not; imagine an employer requiring proof of one's religious beliefs. Should students and employees have to participate in woke indoctrination sessions in which they're required to answer questions about their beliefs to ensure compliance? No, because we wouldn't dream of catechizing people in this way about their religion. [16]

One shouldn't feel bad about not wanting to watch woke movies any more than one would feel bad about not wanting to listen to Christian rock. In my twenties I drove across America several times, listening to local radio stations. Occasionally I'd turn the dial and hear some new song. But the moment anyone mentioned Jesus I'd turn the dial again. Even the tiniest bit of being preached to was enough to make me lose interest.

But by the same token we should not automatically reject everything the woke believe. I'm not a Christian, but I can see that many Christian principles are good ones. It would be a mistake to discard them all just because one didn't share the religion that espoused them. It would be the sort of thing a religious zealot would do.

If we have genuine pluralism, I think we'll be safe from future outbreaks of woke intolerance. Wokeness itself won't go away. There will for the foreseeable future continue to be pockets of woke zealots inventing new moral fashions. The key is not to let them treat their fashions as normative. They can change what their coreligionists are allowed to say every few months if they like, but they mustn't be allowed to change what we're allowed to say. [17]