Week 1 Jan 2023

ctrl F

“All Vaclav wants is for people to look at all the areas of emissions—producing electricity, manufacturing, transportation, and so on—and propose realistic, economically viable plans for reducing emissions in each one.”

Bill Gates

Murdoch

Seth Godin

"As a public speaker, I see far more than my fair share of presentations. Worse, a lot of them are from people getting paid to give them - and they're horrible. Horribly produced, horribly ineffective."

Many professionals who give presentations are not actually selling a product, so does all this selling and pitching stuff really apply, say, to academics, researchers, or to the guys down the hall in the accounting department? This was a question asked in the Atkinson interview. Seth comments:

"It seems to me that if you're not wasting your time and mine, you're here to get me to change my mind, to do something different. And that, my friend, is selling. If you're not trying to persuade, why are you here?"

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in dissent, “Great cases, like hard cases, make bad law. For great cases are called great, not by reason of their real importance in shaping the law of the future, but because of some accident of immediate overwhelming interest which appeals to the feelings and distorts the judgment.

“The classic Harriet Hall quote — “always ask who disagrees and why” — is one of the most influential nuggets of information in my whole life and career. It’s right up there with “billions and billions” and “the 3 most dangerous words in medicine: in my experience” (that one from another SBM alumnus, Dr. Mark Crislip). It’s one of the most important things I have ever learned … because it’s the key to learning about so much more.

The and why is the special sauce. Most reasoning is motivated reasoning. So what’s the motive? Why someone disagrees is critical context.”

Paul Ingraham

PainScience.com Publisher

France - richest man and woman both French

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_female_billionaires

To do

https://www.vogue.com/article/joan-didion-self-respect-essay-1961

eric mazur

lodges in my brain, philosophy student- retirement, alternatives to GDP, poets unacknowledged legislators, doughnut economics, superforecasting

https://intheblack.cpaaustralia.com.au/economy/8-ways-of-measuring-economic-health

Philosophy masters sorbonne

Bubble

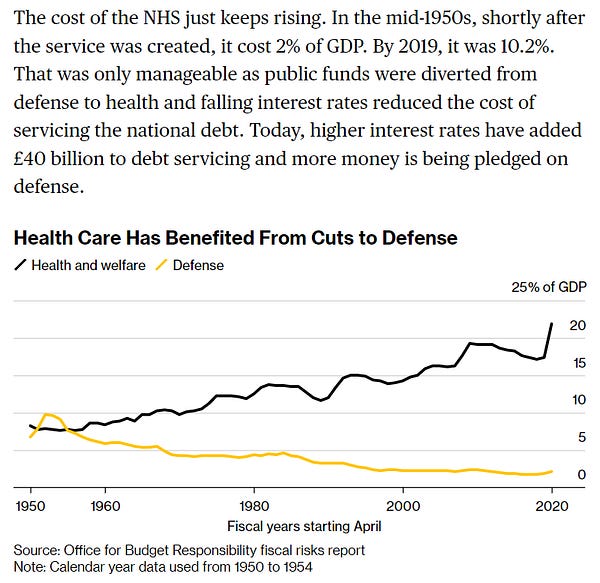

Health care

https://intheblack.cpaaustralia.com.au/economy/8-ways-of-measuring-economic-health

https://technionuk.org/news-post/the-12-best-tech-inventions-of-april-2022/

“Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Shelley

https://interestingliterature.com/2021/12/shelley-poets-unacknowledged-legislators-world-meaning/

A hierophant (Ancient Greek: ἱεροφάντης) is a person who brings religious congregants into the presence of that which is deemed holy.[1] As such, a hierophant is an interpreter of sacred mysteries and arcane principles.

“It was the 30-year anniversary last week of Sky TV's first UK satellite broadcast, a date that somehow passed largely unmarked, no doubt due in part to a widespread perception of Rupert Murdoch and his corporation as some sort of low-browed, profiteering, amoral, sociopathic corporate mega-parasite.”

(now 40) https://www.theguardian.com/media/blog/2013/nov/01/sky-bt-sport-rupert-murdoch

The first thing you need to know about Goldman Sachs is that it’s everywhere. The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money. In fact, the history of the recent financial crisis, which doubles as a history of the rapid decline and fall of the suddenly swindled dry American empire, reads like a Who’s Who of Goldman Sachs graduates.

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/the-great-american-bubble-machine-195229/

Perusall (env) Orwell, Musk satellites, Bettancourt, Arnault, env, UNESCO, Ehrlich, solar, Aaron, connect, global, Gill, crime, marshmallows, obesity, Mesquita, compromise, lists, ethos, trust, heuristics, Gates, Mazur, Hanscom, Murdoch, TOEFL writing

Trojan coffee pot/env/energy

UN sec council. Five permanent members: China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States,

or WEF Davos

There are 3 reasons people steal:

they have to

they think everyone else is stealing

they like it

There are 3 reasons people destroy the environment.

Who are your heroes?

Severn Suzuki, Greta Thunberg, Bella Lack?

Or Rachel Carson, James Lovelock and Douglas Tompkins?

Or all 6?

Which answers are you willing to accept?

Meat once a week/month/year? ration books? Restaurants?

No private jets?

No new oil pipelines? No 900 mile Total pipeline in Uganda?

Reduction in electricity- 6/12 hours a day?

Cap on salaries? Change our way of thinking? Degrowth?

New inventions? Hydrogen? Fusion?

How do you persuade Total not to build the pipeline? And if they don’t, who will?

Is energy from renewables subsidised? Is oil subsidised?

Is Walmart subsidised?

Ralph Norman and Greta Thunberg

Bill Gates- mislabelled tweets

To limit the freedom of the individual in the name of the wellbeing of the collective.

******************************************

Martin Luther King Jr said: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

********************************

George Orwell

“There will be a bitter political struggle, and there will be unconscious and half-conscious sabotage everywhere. At some point or other it may be necessary to use violence. “

“On my return from Spain I thought of exposing the Soviet myth in a story that could be easily understood by almost anyone and which could be easily translated into other languages. However, the actual details of the story did not come to me for some time until one day (I was then living in a small village) I saw a little boy, perhaps ten years old, driving a huge cart-horse along a narrow path, whipping it whenever it tried to turn. It struck me that if only such animals became aware of their strength we should have no power over them, and that men exploit animals in much the same way as the rich exploit the proletariat.”

Konstantin

What is the aim of a Presentation?

The aim is to give information about a topic which the other students will then debate. The topic should therefore be something which you think will divide the other students. So, the death penalty, probably not a good topic. Students will already have a firm view and most students will share the same opinion. Possibly a debate on how the use of the death penalty is being changed by the financial crisis and whether governments’ main principles should be economic or financial in deciding policy might work. Should governments pay for hostages? Maybe.Should governmantes admit they pay for hostages/ pay ransoms/ supply arms to dodgy groups/break the law?

Here’s a few of my recent favourites, with a few ideas as to why they worked. Should dwarf-tossing be allowed? On the face of it, a bit off the wall, but it provoked a good debate on moral acceptability of a wide range of activities.

http://www.worldcourts.com/hrc/eng/decisions/2002.07.15_Wackenheim_v_France.htm

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09649069608410182?journalCode=rjsf20

Are Sciences Po degrees “Mickey Mouse” diplomas? I feared this would not stimulate debate, but it worked well because the presenter gave roles to the students.

Should we burn Hitler’s paintings?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paintings_by_Adolf_Hitler

Read from notes? No. The idea is to look at your presenting and speaking skills, not your reading and writing skills. Use notes? Yes, in moderation. Maybe cue cards?

It doesn’t always work, occasionally a good topic just won’t take off. I would like you to end the presentation by starting the debate, so a presentation giving facts about a country isn’t enough. You must finish the presentation with at least 2 questions- it’s the debate I’m interested in, and your participation in other people’s presentations, not your particular presentation. This is ungraded and should last somewhere between 2 and 10 minutes- this is deliberately vague as the goal is the debate, not the presentation.

Correcting errors/mistakes- what is the best way to do this?

So what are we going to do in this class? (from Scott Thornbury)

Aim for developing intuitions (‘a feel for what is right’) rather than knowledge of rules and terms – this requires a lot of exposure and use, combined with regular ‘grammaticality testing’ , “why is this wrong?”

Pattern sensitization: study texts and transcripts for regularities, even if these are not specifically grammatical (it might just be the repetition of certain words or phrases).

As with the presentations, it won’t always work, but that’s what I’m aiming to do. Please feel free to comment on whether you think these are useful or realistic aims and in what ways I could better achieve them (and to what extent these aims depend on the students).

Compositions

Either print them out and hand them to me, or, preferably, email them to me.

Just how bad are things? How long have we got? Should we save this world or move on to the next one? Should we send humans or eggs on the spaceship? What do we owe the future?

doughnut

song

steady state economy

jobs link gdp

Henry Wallich, who was a former governor of the Federal Reserve in the US, came right out and said this:

"Growth is a substitute for equality of income.

So long as there is growth, there is hope,

and that makes large income differentials tolerable."

And one intervention we could use

would be to have a minimum and a maximum income throughout society.

By a minimum income I don't mean a minimum wage,

conditional on working at McDonalds,

I mean a basic minimum entitlement,”

*****************

fractional reserve banking system

*********************************************

Elizabeth Holmes Theranos

former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger; former Defense Secretary William Perry; former senators Sam Nunn and William Frist; Richard Kovacevich, a former chief executive officer of Wells Fargo & Co.; William Foege, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control; Gary Roughead, a former U.S. Navy admiral; Riley P. Bechtel, a former board chairman of Bechtel Group Inc., and James Mattis, a former U.S. Marine Corps general who later served as a defense secretary in the Trump administration.

Is it “mostly men” who want to discover the elixir of life?

From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs

Although Marx is popularly thought of as the originator of the phrase, the slogan was common within the socialist movement. For example, August Becker in 1844 described it as the basic principle of communism[7] and Louis Blanc used it in 1851.[8] The French socialist Saint-Simonists of the 1820s and 1830s used slightly different slogans such as,"from each according to his ability, to each ability according to its work"[9] or," From each according to his capacity, to each according to his works.”[10] The origin of this phrasing has also been attributed to the French utopian Étienne-Gabriel Morelly

In the Marxist view, such an arrangement will be made possible by the abundance of goods and services that a developed communist system will be capable to produce; the idea is that, with the full development of socialism and unfettered productive forces, there will be enough to satisfy everyone's needs.[4][

literally "Proletarians of all countries, unite!",[5] but soon popularised in English as "Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!").[5][note 1] A variation of this phrase ("Workers of all lands, unite") is also inscribed on Marx's tombstone.

Five years before The Communist Manifesto, this phrase appeared in the 1843 book The Workers' Union by Flora Tristan.[8]

The International Workingmen's Association, described by Engels as "the first international movement of the working class" was persuaded by Engels to change its motto from the League of the Just's "all men are brothers" to "working men of all countries, unite!".

A Socialist Party which genuinely wished to achieve anything would have started by facing several facts which to this day are considered unmentionable in left-wing circles. It would have recognized that England is more united than most countries, that the British workers have a great deal to lose besides their chains, and that the differences in outlook and habits between class and class are rapidly diminishing. In general, it would have recognized that the old-fashioned ‘proletarian revolution’ is an impossibility. But all through the between-war years no Socialist programme that was both revolutionary and workable ever appeared; basically, no doubt, because no one genuinely wanted any major change to happen. The Labour leaders wanted to go on and on, drawing their salaries and periodically swapping jobs with the Conservatives. The Communists wanted to go on and on, suffering a comfortable martyrdom, meeting with endless defeats and afterwards putting the blame on other people. The left-wing intelligentsia wanted to go on and on, sniggering at the Blimps, sapping away at middle-class morale, but still keeping their favoured position as hangers-on of the dividend-drawers. Labour Party politics had become a variant of Conservatism, ‘revolutionary’ politics had become a game of make-believe.

In England there is only one Socialist party that has ever seriously mattered, the Labour Party. It has never been able to achieve any major change, because except in purely domestic matters it has never possessed a genuinely independent policy. It was and is primarily a party of the trade unions, devoted to raising wages and improving working conditions. This meant that all through the critical years it was directly interested in the prosperity of British capitalism. In particular it was interested in the maintenance of the British Empire, for the wealth of England was drawn largely from Asia and Africa. The standard of living of the trade-union workers, whom the Labour Party represented, depended indirectly on the sweating of Indian coolies. At the same time the Labour Party was a Socialist party, using Socialist phraseology, thinking in terms of an old-fashioned anti-imperialism and more or less pledged to make restitution to the coloured races. It had to stand for the ‘independence’ of India, just as it had to stand for disarmament and ‘progress’ generally. Nevertheless everyone was aware that this was nonsense. In the age of the tank and the bombing plane, backward agricultural countries like India and the African colonies can no more be independent than can a cat or a dog. Had any Labour government come into office with a clear majority and then proceeded to grant India anything that could truly be called independence, India would simply have been absorbed by Japan, or divided between Japan and Russia.

To a Labour government in power, three imperial policies would have been open. One was to continue administering the Empire exactly as before, which meant dropping all pretensions to Socialism. Another was to set the subject peoples ‘free’, which meant in practice handing them over to Japan, Italy and other predatory powers, and incidentally causing a catastrophic drop in the British standard of living. The third was to develop a positive imperial policy, and aim at transforming the Empire into a federation of Socialist states, like a looser and freer version of the Union of Soviet Republics. But the Labour Party's history and background made this impossible. It was a party of the trade unions, hopelessly parochial in outlook, with little interest in imperial affairs and no contacts among the men who actually held the Empire together. It would have had to hand the administration of India and Africa and the whole job of imperial defence to men drawn from a different class and traditionally hostile to Socialism

The history of the past seven years has made it perfectly clear that Communism has no chance in western Europe. The appeal of Fascism is enormously greater. In one country after another the Communists have been rooted out by their more up-to-date enemies, the Nazis. In the English-speaking countries they never had a serious footing. The creed they were spreading could appeal only to a rather rare type of person, found chiefly in the middle-class intelligentsia, the type who has ceased to love his own country but still feels the need of patriotism, and therefore develops patriotic sentiments towards Russia.

https://orwell.ru/library/essays/lion/english/e_ter

Contentious

jane fonda on Frankl

while I was writing about this, I came upon a book called "Man's Search for Meaning" by Viktor Frankl. Viktor Frankl was a German psychiatrist who'd spent five years in a Nazi concentration camp. And he wrote that, while he was in the camp, he could tell, should they ever be released, which of the people would be OK, and which would not. And he wrote this: "Everything you have in life can be taken from you except one thing: your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. This is what determines the quality of the life we've lived -- not whether we've been rich or poor, famous or unknown, healthy or suffering. What determines our quality of life is how we relate to these realities, what kind of meaning we assign them, what kind of attitude we cling to about them, what state of mind we allow them to trigger."

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/4187.Primo_Levi?page=4

Week 8

steve j in sweden

https://chomsky.info/

Education

Chomsky on sport

Chomsky on Russell

Old man russell

French intellectuals

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/13/10-most-celebrated-french-thinkers-philosophy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Cohn-Bendit

Shellenberger and Hansen

Drugs

People say we just need to offer homeless addicts more services, including special places where they can use drugs. But yesterday, one block from San Francisco's new drug use site, I discovered mass, open drug use, drug dealing, & psychotic, skeletal addicts on the brink of deathgas

Hard fact; "It takes more electricity to drive the average gasoline car 100 miles, than it does to drive an electric car 100 miles."Michael FeltesJun 9, 2021

Consider gasoline & television as drugs. After all, they give you experiences that change your consciousness which you could not achieve without them and every objection you've outlined to alcohol, tobacco and meth applies to them.

- Massive negative externalities: We're on the verge of hitting 420 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere and that's definitely not nice.

- Vast amounts of time significantly impaired: Have you ever looked at someone else transfixed by a TV show and wondered how different their subjective experience is compared to getting high?

- Tens of thousands killed every year: Only a small portion of the increase in obesity in the US over the past 40 years needs to be attributable to increased TV watching before you're looking at a cause of morbidity & mortality that's on par with lung & mouth cancer.

- Heavily vested interests resist any effort to control use: Well, hell, heavily vested interests protecting their ability to extract economic rent characterizes every aspect of American life these days. How is this any different? Furthermore, now that tobacco smokers have to go outside (because the law does have a role here when it comes to direct impacts of one person's behavior on other people's lives), how do smokers' choices affect my life?

I don't believe Carl Hart when he says that he's not addicted to heroin. I don't think it's wise for people to mess with their opioid receptors for fun because each of us is likely to need those drugs for pain control in the second half of our lives. However, people do things every day that I think are stupid. The salient question is what the threshold for the law to intervene should be.

I favor taking the use of drugs out of the legal framework to a substantial degree since it's not a particularly useful frame. Addicted people need a doctor & a counselor, not a cop & a judge. However, the law should heavily punish behavior under the influence of drugs that risks other people's lives. For instance, in Germany the legal drinking age is 14 with your family and 16 on your own, but if you're caught drinking & driving they drop the hammer on you first time. That, to me, strikes the proper balance between a citizen's civil liberties and societal obligations. Raising children, as always, complicates this question of the state's proper role in the lives of its citizens considerably. I believe addiction is punishment enough and if the government can help parents get clean & sober, that seems considerably more likely to help their children than putting parents in prison.

"There’s this myth that if you just leave these drug addicts alone or whatever, they will eventually decide to get help on their own because addiction sucks."

I don't believe that myth. Some drug addicts will go right over the edge and kill themselves, always. To me, the useful frame for this question is whether making clean drugs available in a regulated market increases or decreases the number of people who will fuck up their lives with hard drugs compared to the status quo. It's undeniable that more people will try drugs under those circumstances. The question is whether getting rid of the incentives in a black market to cut drugs with other chemicals and moving the treatment of addiction entirely out of the legal system would reduce the total amount of suffering, given that the overall number of users will go up.

It's also worth considering, particularly when it comes to opioids, how life circumstances intertwine with addictive drugs. The experience of American soldiers in Vietnam who developed a heroin habit overseas but did not resume that habit once they returned is a good illustration of this. Some of them absolutely did bring that habit back with them ("Sam Stone" is now playing in my head), but the number is surprisingly low. I'd have to refamiliarize myself with the subject to give you more specifics.

"I don’t think a just society lets people kill or maim themselves with hard drugs, not does it allow others to profit from the horror show that is addiction."

I think a just society gets to pick who profits, corporations or criminals. To operationalize this belief, you have to effectively repress black markets. How has that gone so far? How could it be done in a way that's compatible with our society's other ethical commitments?

Moral outrage against the Sackler family is entirely understandable and their ill-gotten gains should absolutely be seized (selling Oxy in and of itself is not what I object to, it's how they marketed the drug), but in the end, how useful is moral outrage? The element of the opioid crisis that really haunts me is realizing how many of my fellow Americans prefer feeling nothing (never having used opioids, that is the closest I can get to the subjective experience) to their regular, everyday life, how many people want to just check out.

https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/open-thread-175/comments

Air pollution waste of energy lights on

Homeless drugs, immigration,

Semi conductor market

The global semiconductor industry is dominated by companies from the United States, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Netherlands.

As of 2021, only three firms are able to manufacture the most advanced semiconductors: TSMC of Taiwan, Samsung of South Korea, and Intel of the United States.[15] Part of this is due to the high capital costs of building foundries. TSMC's latest factory, capable of fabricating 3 nm process semiconductors and completed in 2020, cost $19.5 billion

NXP Semiconductors N.V. is a Dutch multinational semiconductor designer and manufacturer with headquarters in Eindhoven, Netherlands that focuses in the automotive industry. The company employs approximately 29,000 people in more than 30 countries. NXP reported revenue of $11,06 billion in 2021.[3]

Originally spun off from Philips in 2006, NXP completed its initial public offering, on August 6, 2010, with shares trading on NASDAQ under the ticker symbol NXPI. On December 23, 2013, NXP Semiconductors was added to the NASDAQ 100.[4]

On March 2, 2015, it was announced that NXP would merge with Freescale Semiconductor in a $40 billion deal

Some animals are equal

Anatole France

Anatole France In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread.

Le Lys Rouge [The Red Lily] (1894), ch. 7

You think you are dying for your country; you die for the industrialists.

https://scholars-stage.org/i-choose-hannah-arendt/

Thiel on education and google

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-25641941

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jan/07/jane-austen-banknote-abusive-tweets-criado-perez

https://bilderbergmeetings.org/

Do you agree with Scott Galloway?

Elizabeth Holmes is not an outlier. She’s just a part of our storytelling economy in a frothy part of the cycle. Latest #nomercynomalice

Orwell Animal farm

https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/08/archives/the-freedom-of-the-press-orwell.html

Anyone who has lived long in a foreign country will know of instances of sensational items of news—things which on their own merits would get the big headlines—being kept right out of the British press, not because the Government intervened but because of a general tacit agreement that “it wouldn't do” to mention that particular fact. So far as the daily newspapers go, this is easy to understand. The British press is extremely centralized, and most of it is owned by wealthy men who have every motive to be dishonest on certain important topics. But the same kind of veiled censorship also operates in books and periodicals, as well as in plays, films and radio. At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other but it is “not done” to say it, just as in mid‐Victorian times it was “not done” to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness

There always must be, or at any rate there always will be, some degree of censorship, so long as organized societies endure. But freedom, as Rosa Luxemburg said, is “freedom for the other fellow.” The same principle is contained in the famous words of Voltaire: “I detest what you say; I will defend to the death your right to say it.” If the intellectual liberty which without a doubt has been one of the distinguishing marks of Western civilization means anything at all, it means that everyone shall have the right to say and to print what he believes to be the truth, provided only that it does not harm the rest of the community in some quite unmistakeable way. Both capitalist democracy and the Western versions of Socialism have till recently taken that principle for granted.

If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

Charles John Huffam Dickens FRSA (/ˈdɪkɪnz/; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

Orwell on Dickens

https://orwell.ru/

https://orwell.ru/library/reviews/dickens/english/e_chd

One crying evil of his time that Dickens says very little about is child labour. There are plenty of pictures of suffering children in his books, but usually they are suffering in schools rather than in factories. The one detailed account of child labour that he gives is the description in David Copperfield of little David washing bottles in Murdstone & Grinby's warehouse. This, of course, is autobiography. Dickens himself, at the age of ten, had worked in Warren's blacking factory in the Strand, very much as he describes it here. It was a terribly bitter memory to him, partly because he felt the whole incident to be discreditable to his parents, and he even concealed it from his wife till long after they were married.

I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone & Grinby.

And again, having described the rough boys among whom he worked:

No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sunk into this companionship... and felt my hopes of growing up to be a learned and distinguished man crushed in my bosom.

Obviously it is not David Copperfield who is speaking, it is Dickens himself.

Who owns uk media?

The United Kingdom print publishing sector, including books, server, directories and databases, journals, magazines and business media, newspapers and news agencies, has a combined turnover of around £20 billion and employs around 167,000 people.[32] Popular national newspapers include The Times, Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Daily Telegraph. According to a 2021 report by the Media Reform Coalition, 90% of the UK-wide print media is owned and controlled by just three companies, Reach plc (formerly Trinity Mirror), News UK and DMG Media. This figure was up from 83% in 2019.[33] The report also found that six companies operate 83% of local newspapers. The three largest local publishers—Newsquest, Reach and JPI Media—each control a fifth of local press market, more than the share of the smallest 50 local publishers combined.[33

netflix slide deck

5-7, 13-17, 18, 19, 22-27, 30, 31, 36, 60-72, 73-76, 99, 106, 120-122

https://www.slideshare.net/reed2001/culture-1798664

Feynman equations (done) more F. below

“When I see equations, I see the letters in colors. I don’t know why,” wrote Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. “I see vague pictures of Bessel functions with light-tan j’s, slightly violet-bluish n’s, and dark brown x’s flying around.”

Feynman was describing his grapheme-colour (GC) synesthesia – a condition in which individuals sense colours associated with letters and numbers.

Synesthesia is a family of conditions where individuals perceive stimulation through more than one sense.

Remember Galton’s experiments on visual imagination? Some people just don’t have it. And they never figured it out. They assumed no one had it, and when people talked about being able to picture objects in their minds, they were speaking metaphorically.

And the people who did have good visual imaginations didn’t catch them. The people without imaginations mastered this “metaphorical way of talking” so well that they passed for normal. No one figured it out until Galton sat everyone down together and said “Hey, can we be really really clear about exactly how literal we’re being here?” and everyone realized they were describing different experiences.

One of the great mysteries of the brain is the purpose of dreams. And you propose a kind of defensive theory about how the brain responds to darkness.

One of the big surprises of neuroscience was to understand how rapidly these takeovers can happen. If you blindfold somebody for an hour, you can start to see changes where touch and hearing will start taking over the visual parts of the brain. So what I realised is, because the planet rotates into darkness, the visual system alone is at a disadvantage, which is to say, you can still smell and hear and touch and taste in the dark, but you can’t see any more. I realised this puts the visual system in danger of getting taken over every night. And dreams are the brain’s way of defending that territory. About every 90 minutes a great deal of random activity is smashed into the visual system. And because that’s our visual system, we experience it as a dream, we experience it visually. Evolutionarily, this is our way of defending ourselves against visual system takeover when the planet moves into darkness.

I’d certainly like to text 50% faster, but am I going to get an open-head surgery? No, because there’s an expression in neurosurgery: when the air hits your brain, it’s never the same.

https://jancovici.com/en/who-am-i/

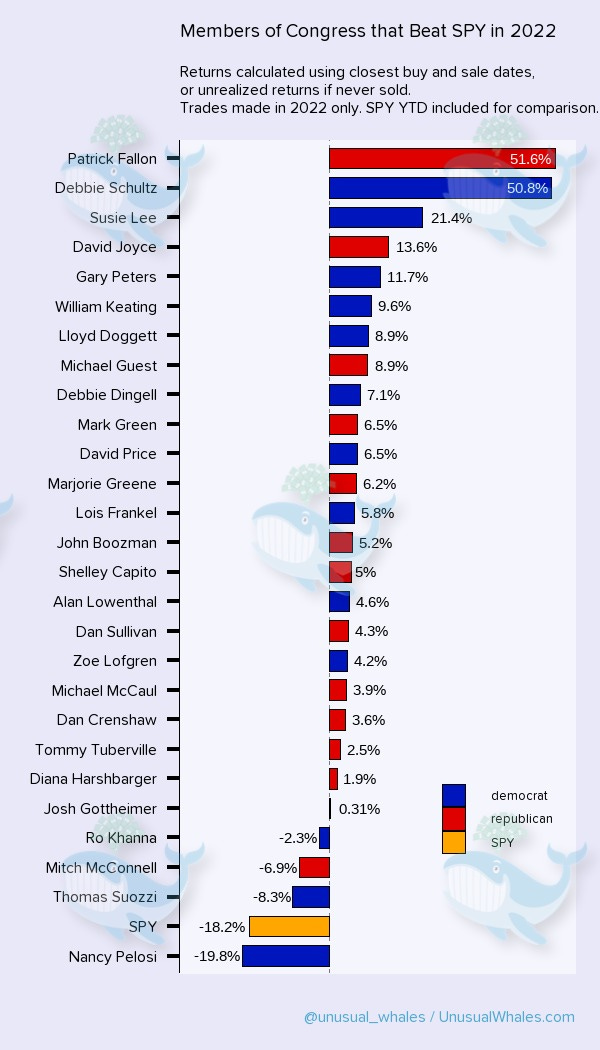

Jim Simons Ray Dalio Ken Griffin Steve Cohen insider trading George Soros John Paulson

https://www.economist.com/culture/2022/02/12/the-strange-tenderness-of-michel-houellebecqs-new-novel

Taleb on actors

Either he is an outlier or, more likely, I have been wrong for decades about actors being fake, image driven, clueless, and devoid of skin in the game, the equivalent of counterfeit money. Worse, I swallowed a two millennia old Graeco-Roman false belief w/o questioning it.

You want the truth?

You can’t handle the truth

Putin singing?

6th extinction

Chernobyl good or bad

has the chernobyl explosion been positive or negative for the environment and the ecosystem

The explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986 was a disaster that had severe consequences for the environment and the ecosystem. The explosion released a large amount of radiation into the atmosphere, which contaminated a large area of land, including parts of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine. This contamination had a negative impact on the environment, including the air, water, and soil.

The explosion and the subsequent release of radiation had a number of negative effects on the ecosystem in the region. Many plants and animals were killed or suffered from radiation sickness, and the populations of some species declined significantly. The contamination also affected the health of people living in the area, as well as the economic well-being of the region. In the years following the disaster, efforts were made to clean up the contaminated areas and to mitigate the effects of the radiation on the environment and the ecosystem. Despite these efforts, the impact of the Chernobyl disaster on the environment and the ecosystem is still being felt today.

https://phys.org/news/2021-04-wild-horses-flourish-chernobyl-years.html

*****************

https://edubenchmark.com/blog/7-tips-to-improve-your-toefl-integrated-writing-score/

Toufik

trading

Les étudiants de deuxième année ont bouclé leur dossier de mobilité il y a quelques jours. 417 étudiants ont passé le TOEFL, avec beaucoup de succès. Je saisis cette occasion pour vous remercier de votre travail au semestre d'automne.

Lors de cette session d'automne, le score moyen au TOEFL d'un.e étudiant.e de 2ème année fut de 95/120, soit un niveau C1. Les étudiant.e.s de Sciences Po "sur-performent" dans toutes les compétences par rapport à la moyenne nationale sauf en Writing où nos étudiant.e.s se situent légèrement au-dessus de la moyenne nationale. C'est la raison pour laquelle il demeure judicieux de faire travailler cette compétence en donnant à écrire au minimum 3 essais de 250-300 mots à la maison pendant le semestre. Je vous prie de bien vouloir trouver ci-joint la charte des langues pour plus de détails.

Au semestre de printemps, ce sera au tour des Masters 2 de passer le TOEFL (ils recevront un voucher très prochainement pour s'inscrire à une session en centre ETS de préférence, sans avance de frais). Pour rappel, il faut présenter un score de 100/120 au TOEFL pour être diplômé de Sciences Po.

The second year students have completed their mobility file a few days ago. 417 students took the TOEFL, with great success.

During this fall semester, the average TOEFL score of a 2nd year student was 95/120, which is a C1 level. Sciences Po students "over-perform" in all skills compared to the national average, except in Writing, where our students are slightly above the national average. This is why it is still a good idea to work on this skill by having students write at least 3 essays of 250-300 words at home during the semester.

In the spring semester, it will be the turn of the Masters 2 students to take the TOEFL (they will receive a voucher very soon to register for a session in an ETS center, preferably without any advance payment). As a reminder, a score of 100/120 on the TOEFL is required to graduate from Sciences Po.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Corruption

Swartz to Lessig

09:19

“Henry David Thoreau: "There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root." This is the root.

Members and staffers and bureaucrats have an increasingly common business model in their head, a business model focused on their life after government, their life as lobbyists. Fifty percent of the Senate between 1998 and 2004 left to become lobbyists, 42 percent of the House. Those numbers have only gone up, and as United Republic calculated last April, the average increase in salary for those who they tracked was 1,452 percent.”

“This is my friend Aaron Swartz. He's Tim's friend. He's friends of many of you in this audience, and seven years ago, Aaron came to me with a question. It was just before I was going to give my first TED Talk. I was so proud. I was telling him about my talk, "Laws that choke creativity." And Aaron looked at me and was a little impatient, and he said, "So how are you ever going to solve the problems you're talking about? Copyright policy, Internet policy, how are you ever going to address those problems so long as there's this fundamental corruption in the way our government works?"

So I was a little put off by this. He wasn't sharing in my celebration. And I said to him, "You know, Aaron, it's not my field, not my field."

He said, "You mean as an academic, it's not your field?

I said, "Yeah, as an academic, it's not my field."

He said, "What about as a citizen? As a citizen."

Now, this is the way Aaron was. He didn't tell. He asked questions.”

https://stuartwiffin.substack.com/p/hierarchy-of-people

https://www.chrismadden.co.uk/cartoon-gallery/environmental-clothes-drying-technology/

https://thehabit.co/knowledge-is-power-france-is-bacon/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(artist)

empiricism

"knowledge is based on experience"

https://youtu.be/G-lN8vWm3m0?t=33

How to outsource medical care/ambulances etc? army? police? charities?

Responsibility and obligation are dismal words in mainstream culture, so perhaps there will be other stories that recognise this process as reciprocity and relationship, in which we give back, in gratitude and respect for all the Earth does for us. Even short of that, we can recognise our self-interest in maintaining the system on which life depends.

Fortunately, as the climate movement has diversified, one new organisation, Clean Creatives, focuses specifically on pressuring advertising and PR agencies to stop doing the industry’s dirty work. Likewise, climate journalists are exposing how fossil fuel money is funding pseudo-environmental opposition to offshore wind turbines.

As the climate activist and oil policy analyst Antonia Juhasz recently told me, the climate movement is now going after every aspect of the fossil fuel industry, including funding by banks and, via the divestment movement, shares held by investors; donations to politicians; insurers; permits for extraction; transport; refinement; emissions, notably through lawsuits concerning their impact; shutting coal-fired power plants; and pushing for a rapid transition to electrification

For example, I see people excoriate the mining, principally for lithium and cobalt, that will be an inevitable part of building renewables – turbines, batteries, solar panels, electric machinery – apparently oblivious to the far vaster scale and impact of fossil fuel mining. If you’re concerned about mining on indigenous land, about local impacts or labour conditions, I give you the biggest mining operations ever undertaken: for oil, gas, and coal, and the hungry machines that must constantly consume them.

Extracting material that will be burned up creates the incessant cycle of consumption on which the fossil fuel industry has grown fabulously rich. It creates climate chaos as well as destruction and contamination at every stage of the process. Globally, burning fossil fuels kills almost 9 million people annually, a death toll larger than any recent war. But that death toll is largely invisible for lack of compelling stories about it.

We have the solutions we need in solar and wind; we just need to build them out and make the transition, fast. Looking to wildly ineffectual carbon sequestration and other undeveloped technologies as a relevant solution is like ignoring the lifeboats at hand in the hope that fancy new ones are coming when the ship is sinking and speed is of the essence.

if we can’t win everything, then we lose everything. There are so many doom-soaked stories out there – about how civilisation, humanity, even life itself, are scheduled to die out. This apocalyptic thinking is due to another narrative failure: the inability to imagine a world different than the one we currently inhabit.

While I often hear people casually assert that our world is doomed, no reputable scientist makes such claims.

A climate story we urgently need is one that exposes who is actually responsible for climate chaos. It’s been popular to say that we are all responsible, but Oxfam reports that over the past 25 years, the carbon impact of the top 1% of the wealthiest human beings was twice that of the bottom 50%, so responsibility for the impact and the capacity to make change is currently distributed very unevenly.

By saying “we are all responsible”, we avoid the fact that the global majority of us don’t need to change much, but a minority needs to change a lot.

Last year, the veteran environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote a brilliant analysis pointing out that if you have money in one of the banks funding fossil fuels – especially, in the US, Wells Fargo, Chase, Citi, and Bank of America – your retirement funds or savings account may have a much larger climate footprint than you do. The impact of your diet and how you get to work may pale in comparison to the impact of your money in the bank. The vegan on the bicycle may still be contributing to climate chaos if her life savings are in a bank lending her money to the fossil fuel industry.

Individual impact, leaving the ultra-wealthy aside, matters mostly in the aggregate. And in aggregate we can change that. On 21 March, McKibben, via his new climate group Third Act (on whose advisory board I sit), and dozens of other climate groups will be organising actions by people with money in, or credit cards from, the key US banks, to try to force those institutions to stop funding fossil fuels. Our greatest power lies in our roles as citizens, not consumers, when we can band together to collectively change how our world works.

You ban the insecticide DDT, and a lot of bird species stop dying out. You ban chlorofluorocarbons, and the hole in the ozone layer stops growing.

*************************

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trojan_Room_coffee_pot

***************************

“Our use of Perusall at both Mercy College in NY, where I teach undergraduate Cultural Anthropology, Environmental Sustainability, and Justice and Environmental Psychology, and at the University of South Florida’s Patel College of Global Sustainability where I teach graduate courses in Climate Mitigation and Adaptation, Navigating the Food/Energy/Water Nexus, Zero-Waste Concepts for a Circular Economy and Envisioning and Communicating Sustainability,”

Thomas Culhane, University of South Florida, Patel College of Global Sustainability

https://www.perusall.com/exchange-2022-program

Who is the world's richest woman? After the death of reigning richest woman on earth L'Oreal heiress Liliane Bettencourt last week, the answer wasn't immediately clear.

But Bloomberg has declared that Bettencourt's only daughter, Francoise Bettencourt Meyers, is now officially the world's richest woman, ahead of Alice Walton, the Walmart heiress. Bloomberg puts Bettencourt Meyers' net worth at $42 billion, compared to $37.7 billion for Walton.

https://money.com/worlds-richest-woman-francoise-bettencourt-meyers-loreal-walmart/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_female_billionaires

Françoise Bettencourt Meyers (French: [fʁɑ̃swaz bɛtɑ̃kuʁ mɛjɛʁs]; born 10 July 1953) is a French businesswoman, philanthropist, writer, pianist and billionaire heiress, the richest woman in the world, with an estimated net worth of US$75.3 billion as of March 2022, according to Forbes. She is the only child, heiress of Liliane Bettencourt and granddaughter of L'Oréal founder Eugène Schueller. Her mother died in September 2017, after which her fortune tripled with her investments through her family holding company, Tethys Invest, and the high valuation of L'Oréal shares on the stock exchange.[1]

Liliane Henriette Charlotte Bettencourt (French pronunciation: [lil.jan be.tɑ̃.kuːʁ]; née Schueller; 21 October 1922 – 21 September 2017) was a French heiress, socialite and businesswoman. She was one of the principal shareholders of L'Oréal. At the time of her death, she was the richest woman, and the 14th richest person in the world, with a net worth of US$44.3 billion.

In 1950, she married French politician André Bettencourt, who served as a cabinet minister in French governments of the 1960s and 1970s and rose to become deputy chairman of L'Oréal. Mr. Bettencourt had been a member of La Cagoule, a violent French fascist pro-Nazi group that Liliane's father, a Nazi sympathizer, had funded and supported in the 1930s and whose members were arrested in 1937. After the war, her husband, like other members of La Cagoule, was given refuge at L'Oréal despite his politically inconvenient past.[7]

In 1957, Bettencourt inherited the L'Oréal fortune when her father died, becoming the principal shareholder. In 1963, the company went public, although Bettencourt continued to own a majority stake. In 1974, in fear that the company would be nationalised after the French elections, she exchanged almost half of her stake for a three percent (3%) stake in Nestlé S.A.[10]

As of December 2012, Bettencourt owned 185,661,879 (30.5%) of the outstanding shares of L'Oréal, of which 76,441,389 (12.56%) shares are effectively held in trust (for her daughter). The remainder is owned as follows: 178,381,021 (29.78%) shares owned by Nestlé, 229,933,941 (37.76%) shares are publicly held, and the remainder are held as treasury stock or in the company savings plan.

, in 2007 Bettencourt was jointly "awarded" a Black Planet Award, an award given for destroying the planet, along with Peter Brabeck-Letmathe for proliferating contaminated baby food, monopolising water resources, and tolerating child labour.[2

Bettencourt was reported to be one of the most high-profile victims of Bernard Madoff's Ponzi scheme, losing €22 million. She was the first investor in a fund managed by Access International Advisors, which was co-founded by René-Thierry Magon de la Villehuchet. De la Villehuchet killed himself on 22 December 2008, after it became known that his funds had invested a substantial amount of their capital with Madoff.[37]

In June 2010, during the Bettencourt affair, Bettencourt became embroiled in a high-level French political scandal after other details of the tape recordings made by her butler became public. The tapes allegedly picked up conversations between Bettencourt and her financial adviser, Patrice de Maistre, which indicate that Bettencourt may have avoided paying taxes by keeping a substantial amount of cash in undeclared Swiss bank accounts. The tapes also allegedly captured a conversation between Bettencourt and French budget minister Éric Woerth, who was soliciting a job for his wife managing Bettencourt's wealth, while running a high-profile campaign to catch wealthy tax evaders as the budget minister.[38] Moreover, Bettencourt received a €30 million tax rebate while Woerth was budget minister.[39]

*********

Mazur

Don’t teach- help students learn

Lee Shulman - the plural of anecdote is not data

8.48 brains

9.47 notes

10.49 build mental models

14.15 ss not teacher convince

14.34 the more you know, the harder it is to teach?

cf Feynman

15.46 Socratic questioning

**************************

Harvard courses

Stop bullying! Make students engaged!

CHIEF OF SECTION (EDUCATION)

UNESCO Paris, Île-de-France, France On-site 2 weeks ago Over 200 applicants

Full-time · Mid-Senior level

1,001-5,000 employees · International Affairs

Under the overall authority of the Assistant Director-General of Education (ADG/ED), and the direct supervision of the Director of the Division for Peace and Sustainable Development (ED/PSD), the incumbent will lead the design, coordination and execution for programme and projects in the Section of Health and Education , and play a significant role in policy and strategy direction, development and integration, and resource optimization.

Be responsible for all issues regarding international normative instruments related to the work of the Section, and in alignment with Priority Africa, Gender Equality and the meaningful engagement of children and young people, and aligned to the UNESCO Strategy on Education for Health and Well-being and its three pillars on comprehensive sexuality education, safe learning environments free from school violence including bullying, and school health and nutrition;

*******

corrupt, unscientific, climate risk

pork

open borders

c’est un paternoster

psych

solar panels

Aaron Swartz died on January 11, 2013.

Here is a link to his blog.

http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/

He reviews the books he read that year- I love this casual dismissal of QED because it’s not Feynman. He was also light years ahead of most people in noticing people like Yudkowsky and Taibbi (in the news today because of the twitter files).Duflo and Banerjee- long before they won the Nobel prize. And recommending Gallwey a long time before Bill Gates! Lean business methods, Christopher Hitchens, Joan Didion, Tony Blair and how accounting firms work- this was just one year for Swartz!

QED by Peter Parnell

Not bad, by any stretch, but on the page, for anyone who’s familiar with Feynman’s actual writings, this can’t help but feel thin.

Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality by Eliezer Yudkowsky

The eXile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia, Matt Taibbi and Mark Ames

Matt Taibbi is my favorite political journalist. He writes with a raw honesty that manages to be both politically biting and hilarious.

Poor Economics by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo

God, what a book! Poor Economics is a series of tales of foreigners trying to save the far-flung poor, while failing to realize not only that their developed-country ideas are terrible disasters in practice, but also that everything they've learned to think of as solid—even something as simple as measuring distance—is far more fraught, and complex, and political than they ever could have imagined. It's a stunning feeling to have the basic building blocks of your world questioned and crumbled before you—and a powerful lesson in the value of self-skepticism for everyone who's trying to do something.

The Inner Game of Tennis by Timothy Gallwey

This book touched me deeply and made me rethink the entire way I approached life; it's about vastly more than just tennis. I can't really describe it, but I can recommend this video with Alan Kay and the author that will blow your mind.

video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=50L44hEtVos

Good point from Helena Luna.

It's sad you managed to included only few women....

https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2577-a-hacktivist-reading-list-aaron-swartz-s-recommended-reading

The conversation eventually turned to the fact that Palanpur farmers sow their winter crops several weeks after the date at which yields would be maximized. The farmers do not doubt that earlier planting would give them larger harvests, but no one the farmer explained, is willing to be the first to plant, as the seeds on any lone plot would be quickly eaten by birds. I asked if a large group of farmers, perhaps relatives, had ever agreed to sow earlier, all planting on the same day to minimize losses. “If we knew how to do that,” he said, looking up from his hoe at me, “we would not be poor.”

http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/bowles

Haiti: After the Quake by Paul Farmer

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice by Christopher Hitchens

Mother Teresa is a byword for saintliness, but have you ever stopped to ask why? Christopher Hitchens makes a convincing case that she’s something closer to a monster. Everyone I’ve told about this book is shocked by the concept, but it’s a short book with a pretty compelling argument.

Joan: Forty Years of Life, Loss, and Friendship with Joan Didion by Sara Davidson

It’s hard to shake the feeling that this book is merely the author attempting to cash in on their minor friendship with Joan Didion, but I love Didion so much that I’m just grateful for the stories.

The Ghost [Writer] by Robert Harris

It’s hard to shake the feeling that a big part of the appeal of this book is watching Tony Blair get arrested for war crimes, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a first-rate political thriler.

The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

Ries presents a translation of the Toyota Production System to startups — and it’s so clearly the right way to run a startup that it’s hard to imagine how we got along before it. Unfortunately, the book has become so trendy that I find many people claiming to swear allegiance to it who clearly missed the point entirely.

The Great Stagnation by Tyler Cowen

A dreadful little book, which boils down to nothing more than a vast tract of economic illiteracy. Take just the insanity that is chapter 2. Cowen takes as his dictum:

The larger the role of government in the economy, the more the published figures for GDP growth are overstating improvements in our living standard.

For example, as government-insured health care takes up a larger proportion of our country’s spending, we can’t accurately measure how our living standards are improving since it’s paid for at set rates by government instead of through a competitive market process to set accurate prices.

Private Firms Working in the Public Interest by Abigail Bugbee Brown

Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, Olympus — why is there so much accounting fraud? Why isn’t this stuff caught? In this serious but briskly-written work, Abigail Brown explains the incredible story of how accounting firms actually work. Paid by the people they’re supposed to be auditing, accounting firms have developed an elaborate culture of corruption, letting them aid and abet the most egregious forms of dishonesty.

(Disclosure: Ms. Brown and I were lab fellows together at the Harvard Center for Ethics.)

http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/books2011

Only connect Forster

This term we will be looking at connection and connections.

Brene Brown from here 3.12 to 4.07

https://youtu.be/iCvmsMzlF7o?t=192

But, does one topic have to be connected to the next or can we just flit like a butterfly from topic to topic, alighting where the mood takes us, quickly departing if there is no interest in this particular flower?

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apophenia

apophenia

noun

ap·o·phe·nia ˌa-pə-ˈfē-nē-ə

: the tendency to perceive a connection or meaningful pattern between unrelated or random things (such as objects or ideas)What psychologists call apophenia—the human tendency to see connections and patterns that are not really there—gives rise to conspiracy theories.—George Johnson

pareidolia

noun

par·ei·do·lia ˌper-ˌī-ˈdō-lē-ə -ˈdōl-yə

: the tendency to perceive a specific, often meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual patternThe scientific explanation for some people is pareidolia, or the human ability to see shapes or make pictures out of randomness. Think of the Rorschach inkblot test.—Pamela Ferdinand

Last term we looked at the question- can we predict the future and we discovered the answer depends on which future you’re describing- weather, rain, temperature, where, stocks, shares, hedge funds,the price of oil.

The Inner Game of tennis

Best guide to getting out of your own way: The Inner Game of Tennis, by Timothy Gallwey. This book from 1974 is a must-read for anyone who plays tennis, but I think even people who have never played will get something out of it. Gallwey argues that your state of mind is just as important—if not more important—than your physical fitness. He gives excellent advice about how to move on constructively from mistakes, which I’ve tried to follow both on and off the court over the years.

Greenwald Taibbi

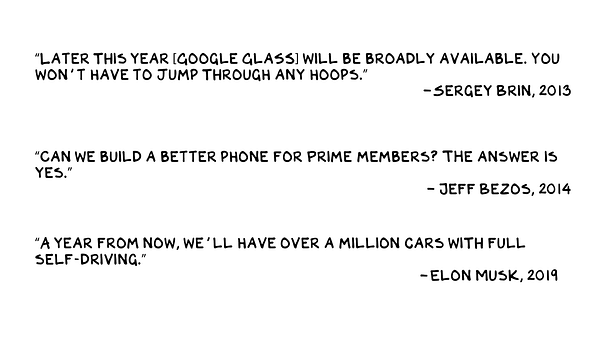

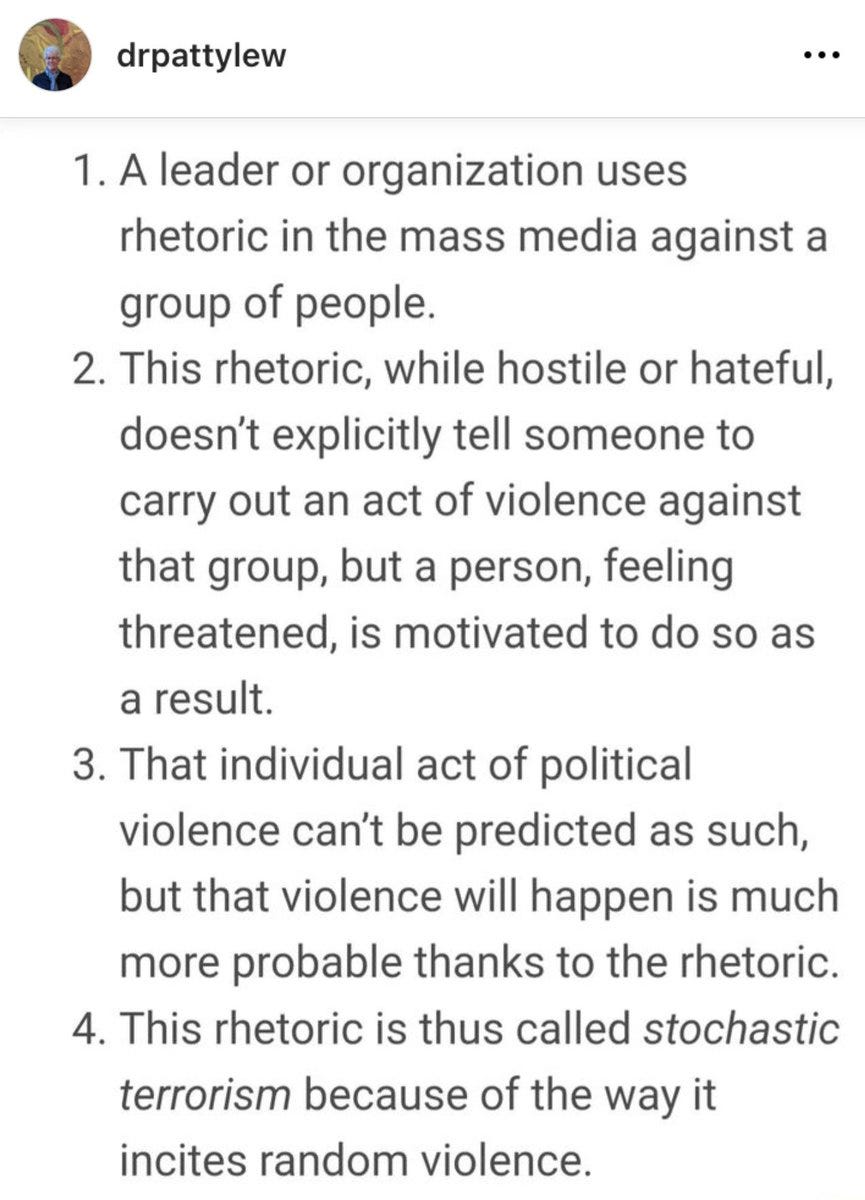

some trending vocabulary we’ll be looking at:

shill, orthogonal, stochastic, iterate

twitter stochastic terrorism

When “leaders” dehumanize groups of people, they indirectly incite violence against “others”. #StochasticTerrorism Colorado Springs night club - LBGTQ Buffalo Tops - Blacks El Paso Walmart - Mexican Americans Pittsburgh Synagogue - Jews #January6 US Capitol - Democrats & Pence

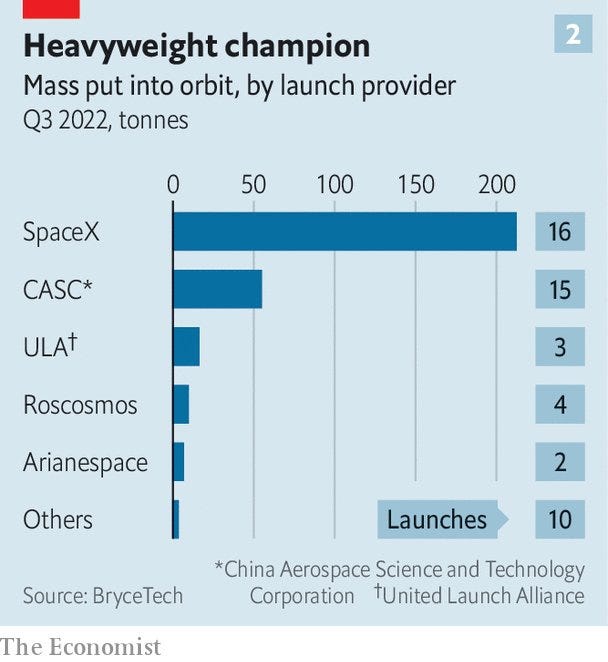

Musk

“I tend to approach things from a physics framework,” Musk said in an interview. “Physics teaches you to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. So I said, okay, let’s look at the first principles. What is a rocket made of? Aerospace-grade aluminum alloys, plus some titanium, copper, and carbon fiber. Then I asked, what is the value of those materials on the commodity market? It turned out that the materials cost of a rocket was around two percent of the typical price.”

Instead of buying a finished rocket for tens of millions, Musk decided to create his own company, purchase the raw materials for cheap, and build the rockets himself. SpaceX was born.

Within a few years, SpaceX had cut the price of launching a rocket by nearly 10x while still making a profit. Musk used first principles thinking to break the situation down to the fundamentals, bypass the high prices of the aerospace industry, and create a more effective solution.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonewall_riots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PayPal_Mafia

The PayPal Mafia phenomenon has been compared to the founding of Intel in the late 1960s by engineers who had earlier founded Fairchild Semiconductor after leaving Shockley Semiconductor.[3] They are discussed in journalist Sarah Lacy's book Once You're Lucky, Twice You're Good.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traitorous_eight

https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/14/jobs-061505/

I met with David Packard and Bob Noyce and tried to apologize for screwing up so badly.

Sirhan sirhan

Doesn’t remember

on Robert Frost 4.00 to 5.30 Hitler

3.49

Lho in Russia

patsy

Test EF https://www.ef.com/wwen/english-resources/english-test/

2.9

Right to sex

Sandwich

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/08/amia-srinivasan-the-right-to-sex-interview

Jacques Derrida

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Michel Foucault,

Views on underage sex and pedophilia

Foucault was a proponent of adult-child underage sex and of pedophilia, considering them a form of liberation for both actors;[185][186][187] he argued young children could give sexual consent.[188] In 1977, along with Jean-Paul Sartre, Jacques Derrida, and other intellectuals, Foucault signed a petition to the French parliament calling for the decriminalization of all "consensual" sexual relations between adults and minors below the age of fifteen, the age of consent in France.[189][190]

Cannabis yields Ben Cort

Slide

Add these numbers

Comm strategies

Jim kwik

Theranos tedtalk

60 mins

Spoof

Pg um er

Pg on Jessica http://www.paulgraham.com/jessica.html

Conv

3

More speaking

How to ace the toefl

Grading criteria

Words per response

Schwa

ot long after Steve Jobs got married, in 1991, he moved with his wife to a nineteen-thirties, Cotswolds-style house in old Palo Alto. Jobs always found it difficult to furnish the places where he lived. His previous house had only a mattress, a table, and chairs. He needed things to be perfect, and it took time to figure out what perfect was. This time, he had a wife and family in tow, but it made little difference. “We spoke about furniture in theory for eight years,” his wife, Laurene Powell, tells Walter Isaacson, in “Steve Jobs,” Isaacson’s enthralling new biography of the Apple founder. “We spent a lot of time asking ourselves, ‘What is the purpose of a sofa?’ ”

Jobs’s sensibility was more editorial than inventive. “I’ll know it when I see it,” he said.Illustration by André Carrilho

It was the choice of a washing machine, however, that proved most vexing. European washing machines, Jobs discovered, used less detergent and less water than their American counterparts, and were easier on the clothes. But they took twice as long to complete a washing cycle. What should the family do? As Jobs explained, “We spent some time in our family talking about what’s the trade-off we want to make. We ended up talking a lot about design, but also about the values of our family. Did we care most about getting our wash done in an hour versus an hour and a half? Or did we care most about our clothes feeling really soft and lasting longer? Did we care about using a quarter of the water? We spent about two weeks talking about this every night at the dinner table.”

Steve Jobs, Isaacson’s biography makes clear, was a complicated and exhausting man. “There are parts of his life and personality that are extremely messy, and that’s the truth,” Powell tells Isaacson. “You shouldn’t whitewash it.” Isaacson, to his credit, does not. He talks to everyone in Jobs’s career, meticulously recording conversations and encounters dating back twenty and thirty years. Jobs, we learn, was a bully. “He had the uncanny capacity to know exactly what your weak point is, know what will make you feel small, to make you cringe,” a friend of his tells Isaacson. Jobs gets his girlfriend pregnant, and then denies that the child is his. He parks in handicapped spaces. He screams at subordinates. He cries like a small child when he does not get his way. He gets stopped for driving a hundred miles an hour, honks angrily at the officer for taking too long to write up the ticket, and then resumes his journey at a hundred miles an hour. He sits in a restaurant and sends his food back three times. He arrives at his hotel suite in New York for press interviews and decides, at 10 p.m., that the piano needs to be repositioned, the strawberries are inadequate, and the flowers are all wrong: he wanted calla lilies. (When his public-relations assistant returns, at midnight, with the right flowers, he tells her that her suit is “disgusting.”) “Machines and robots were painted and repainted as he compulsively revised his color scheme,” Isaacson writes, of the factory Jobs built, after founding NeXT, in the late nineteen-eighties. “The walls were museum white, as they had been at the Macintosh factory, and there were $20,000 black leather chairs and a custom-made staircase. . . . He insisted that the machinery on the 165-foot assembly line be configured to move the circuit boards from right to left as they got built, so that the process would look better to visitors who watched from the viewing gallery.”

Isaacson begins with Jobs’s humble origins in Silicon Valley, the early triumph at Apple, and the humiliating ouster from the firm he created. He then charts the even greater triumphs at Pixar and at a resurgent Apple, when Jobs returns, in the late nineteen-nineties, and our natural expectation is that Jobs will emerge wiser and gentler from his tumultuous journey. He never does. In the hospital at the end of his life, he runs through sixty-seven nurses before he finds three he likes. “At one point, the pulmonologist tried to put a mask over his face when he was deeply sedated,” Isaacson writes:

Jobs ripped it off and mumbled that he hated the design and refused to wear it. Though barely able to speak, he ordered them to bring five different options for the mask and he would pick a design he liked. . . . He also hated the oxygen monitor they put on his finger. He told them it was ugly and too complex.

One of the great puzzles of the industrial revolution is why it began in England. Why not France, or Germany? Many reasons have been offered. Britain had plentiful supplies of coal, for instance. It had a good patent system in place. It had relatively high labor costs, which encouraged the search for labor-saving innovations. In an article published earlier this year, however, the economists Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr focus on a different explanation: the role of Britain’s human-capital advantage—in particular, on a group they call “tweakers.” They believe that Britain dominated the industrial revolution because it had a far larger population of skilled engineers and artisans than its competitors: resourceful and creative men who took the signature inventions of the industrial age and tweaked them—refined and perfected them, and made them work.

In 1779, Samuel Crompton, a retiring genius from Lancashire, invented the spinning mule, which made possible the mechanization of cotton manufacture. Yet England’s real advantage was that it had Henry Stones, of Horwich, who added metal rollers to the mule; and James Hargreaves, of Tottington, who figured out how to smooth the acceleration and deceleration of the spinning wheel; and William Kelly, of Glasgow, who worked out how to add water power to the draw stroke; and John Kennedy, of Manchester, who adapted the wheel to turn out fine counts; and, finally, Richard Roberts, also of Manchester, a master of precision machine tooling—and the tweaker’s tweaker. He created the “automatic” spinning mule: an exacting, high-speed, reliable rethinking of Crompton’s original creation. Such men, the economists argue, provided the “micro inventions necessary to make macro inventions highly productive and remunerative.”

Was Steve Jobs a Samuel Crompton or was he a Richard Roberts? In the eulogies that followed Jobs’s death, last month, he was repeatedly referred to as a large-scale visionary and inventor. But Isaacson’s biography suggests that he was much more of a tweaker. He borrowed the characteristic features of the Macintosh—the mouse and the icons on the screen—from the engineers at Xerox parc, after his famous visit there, in 1979. The first portable digital music players came out in 1996. Apple introduced the iPod, in 2001, because Jobs looked at the existing music players on the market and concluded that they “truly sucked.” Smart phones started coming out in the nineteen-nineties. Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, more than a decade later, because, Isaacson writes, “he had noticed something odd about the cell phones on the market: They all stank, just like portable music players used to.” The idea for the iPad came from an engineer at Microsoft, who was married to a friend of the Jobs family, and who invited Jobs to his fiftieth-birthday party. As Jobs tells Isaacson:

This guy badgered me about how Microsoft was going to completely change the world with this tablet PC software and eliminate all notebook computers, and Apple ought to license his Microsoft software. But he was doing the device all wrong. It had a stylus. As soon as you have a stylus, you’re dead. This dinner was like the tenth time he talked to me about it, and I was so sick of it that I came home and said, “Fuck this, let’s show him what a tablet can really be.”

Even within Apple, Jobs was known for taking credit for others’ ideas. Jonathan Ive, the designer behind the iMac, the iPod, and the iPhone, tells Isaacson, “He will go through a process of looking at my ideas and say, ‘That’s no good. That’s not very good. I like that one.’ And later I will be sitting in the audience and he will be talking about it as if it was his idea.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jobs’s sensibility was editorial, not inventive. His gift lay in taking what was in front of him—the tablet with stylus—and ruthlessly refining it. After looking at the first commercials for the iPad, he tracked down the copywriter, James Vincent, and told him, “Your commercials suck.”

“Well, what do you want?” Vincent shot back. “You’ve not been able to tell me what you want.”

“I don’t know,” Jobs said. “You have to bring me something new. Nothing you’ve shown me is even close.”

Vincent argued back and suddenly Jobs went ballistic. “He just started screaming at me,” Vincent recalled. Vincent could be volatile himself, and the volleys escalated.

When Vincent shouted, “You’ve got to tell me what you want,” Jobs shot back, “You’ve got to show me some stuff, and I’ll know it when I see it.”

I’ll know it when I see it. That was Jobs’s credo, and until he saw it his perfectionism kept him on edge. He looked at the title bars—the headers that run across the top of windows and documents—that his team of software developers had designed for the original Macintosh and decided he didn’t like them. He forced the developers to do another version, and then another, about twenty iterations in all, insisting on one tiny tweak after another, and when the developers protested that they had better things to do he shouted, “Can you imagine looking at that every day? It’s not just a little thing. It’s something we have to do right.”

VIDEO FROM THE NEW YORKER

Jamaica Kincaid and Charlayne Hunter-Gault on Hope in the Black Community

The famous Apple “Think Different” campaign came from Jobs’s advertising team at TBWAChiatDay. But it was Jobs who agonized over the slogan until it was right:

They debated the grammatical issue: If “different” was supposed to modify the verb “think,” it should be an adverb, as in “think differently.” But Jobs insisted that he wanted “different” to be used as a noun, as in “think victory” or “think beauty.” Also, it echoed colloquial use, as in “think big.” Jobs later explained, “We discussed whether it was correct before we ran it. It’s grammatical, if you think about what we’re trying to say. It’s not think the same, it’s think different. Think a little different, think a lot different, think different. ‘Think differently’ wouldn’t hit the meaning for me.”

The point of Meisenzahl and Mokyr’s argument is that this sort of tweaking is essential to progress. James Watt invented the modern steam engine, doubling the efficiency of the engines that had come before. But when the tweakers took over the efficiency of the steam engine swiftly quadrupled. Samuel Crompton was responsible for what Meisenzahl and Mokyr call “arguably the most productive invention” of the industrial revolution. But the key moment, in the history of the mule, came a few years later, when there was a strike of cotton workers. The mill owners were looking for a way to replace the workers with unskilled labor, and needed an automatic mule, which did not need to be controlled by the spinner. Who solved the problem? Not Crompton, an unambitious man who regretted only that public interest would not leave him to his seclusion, so that he might “earn undisturbed the fruits of his ingenuity and perseverance.” It was the tweaker’s tweaker, Richard Roberts, who saved the day, producing a prototype, in 1825, and then an even better solution in 1830. Before long, the number of spindles on a typical mule jumped from four hundred to a thousand. The visionary starts with a clean sheet of paper, and re-imagines the world. The tweaker inherits things as they are, and has to push and pull them toward some more nearly perfect solution. That is not a lesser task.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/11/14/the-tweaker

Check your privilege

https://www.buzzfeed.com/regajha/how-privileged-are-you

https://resourcegeneration.org/start-your-journey/quiz/

motte and bailey

A shill, also called a plant or a stooge, is a person who publicly helps or gives credibility to a person or organization without disclosing that they have a close relationship with said person or organization.

biases, heuristics (see below) https://achillesandaristotle.com/2014/06/14/dismal-news/

https://www.achillesjustice.com/post/attitudes-heuristics-and-bias

digress

1. How to Make Wealth:

http://paulgraham.com/wealth.html

2. How to Start a Startup

http://paulgraham.com/start.html

3. Hiring is Obsolete (maybe his best)

http://paulgraham.com/hiring.html

4. The Hardest Lesson for Startups to Learn

http://paulgraham.com/startuplessons.html

5. The 18 Mistakes that Kill Startups

http://paulgraham.com/startupmistakes.html

6. Why To Not Not Start a Startup

http://paulgraham.com/notnot.html

7. Holding a Program in One's Head

http://paulgraham.com/head.html

8. Cities & Ambition (cited by Jeff)

http://paulgraham.com/cities.html

9. Relentlessly Resourcesful

http://paulgraham.com/relres.html

and 10. What Startups are Really Like (previously cited by Charlie)

Schumpeter The case against globaloney

Apr 20th 2011

GEOFFREY CROWTHER, editor of The Economist from 1938 to 1956, used to advise young journalists to “simplify, then exaggerate”. He might have changed his advice if he had lived to witness the current debate on globalisation. There is a lively discussion about whether it is good or bad. But everybody seems to agree that globalisation is a fait accompli: that the world is flat, if you are a (Tom) Friedmanite, or that the world is run by a handful of global corporations, if you are a (Naomi) Kleinian.

Pankaj Ghemawat of IESE Business School in Spain is one of the few who has kept his head on the subject. For more than a decade he has subjected the simplifiers and exaggerators to a barrage of statistics. He has now set out his case—that we live in an era of semi-globalisation at most—in a single volume, “World 3.0”, that should be read by anyone who wants to understand the most important economic development of our time.

Mr Ghemawat points out that many indicators of global integration are surprisingly low. Only 2% of students are at universities outside their home countries; and only 3% of people live outside their country of birth. Only 7% of rice is traded across borders. Only 7% of directors of S&P 500 companies are foreigners—and, according to a study a few years ago, less than 1% of all American companies have any foreign operations. Exports are equivalent to only 20% of global GDP.

________________

=SIR – Liberal economists invariably support frictionless labour markets. In an ideal world we would have nothing else. But in the world we’ve got, the question has to be asked: does a government have an obligation to protect the livelihoods of those citizens who were born or are already resident in a country? This is one of the issues that has fuelled the tea party and it is not going to go away.

Karl Sutterfield

Denver

SIR – Your leader calling for the lifting of limits on skilled immigrants to Britain (“Scrap the cap”, November 20th) ignored some of the main reasons to keep such restrictions. Britain’s infrastructure cannot cope with more people. The country is already bursting at the seams. Skilled immigrants with large families often turn to local councils for housing, but the authorities have nowhere to put them; hospitals and schools in inner city areas are overwhelmed.

A.J. Shearburn

Cape Town

SIR – Immigration is the backbone of globalisation. The grievances of those who fear immigrants are understandable, but bigotry and discrimination are not acceptable and people should overcome their fears. Immigration is a very natural thing and trying to cap it is like trying to cap the rain.

Okwechime Ekene

Glasgow

WikiLeaks' latest

More dope, no highs

Blushes, frowns but no explosions in the latest WikiLeaks’ disclosures

Dec 9th 2010 |

DISINGENUOUS and caustic, yes. But demonising America’s diplomats on the basis of the few hundred cables disclosed so far would be hard. Nor is it easy to argue that WikiLeaks has done devastating damage to America’s interests.

The most controversial disclosure in recent days was probably a long list of commercial and other installations deemed critical to America’s national security. That included the landing points of undersea cables; the names of firms making vital vaccines; and big ports. But the list had obvious omissions and nothing on it was secret. Published on the Pentagon’s website it would hardly have raised an eyebrow.

More damaging may be reports from diplomats in north Africa, which underline what had previously been just savage gossip. A former American ambassador to Morocco is quoted as bemoaning “the appalling greed of those close to King Muhammad VI”. A company owned by the royal family, a private secretary and a political-party leader are all named in terms that would, in a journalistic context, risk a libel suit. The cables also depict Morocco’s military as riddled with corruption, “particularly at the highest levels”.